I have no casual register.

This is a running joke among my friends who live in generational poverty. They delight in poking fun at the way I speak, because it is not all that different from the way I write. My sentences are correct grammatically. There is very little slang. Once I read aloud from a book during one of our educational sessions together, and my generationally poor friends said they could listen to me for hours because it sounded like I was performing the material instead of just reading aloud from an instructional manual (which is, in fact, what I was doing). That is a nice compliment, but the flip side is hilarious ridicule when I attempt to awkwardly work phrases of the street into my otherwise pristine, middle-class vernacular. No one is my homeboy. The only peeps I have come at Easter. The skills that help me thrive at work would marginalize and separate me out on the street.

When people who grew up with middle-class norms sit across the table from people who grew up in poverty, there are far more invisible walls dividing them than bank statements and access to resources. There is a cultural collision not unlike the one a Westerner experiences when he travels to Uganda, Haiti, or China and sits across the table from new friends. I went to a restaurant with a Chinese pastor in downtown Hong Kong and took a seat at a round table with my back to the wall, facing the room. I was the youngest guy in our party, and my gracious host informed me, somewhere around dessert, that I had taken the seat of honor usually reserved for the most powerful or honorable in the group (i.e. not the young guy). We all enjoyed the moment, but nevertheless I had broken an invisible, cultural rule based on traditions, values, and common sense—a rule unknown to me because I did not grow up learning the rules of Asian culture instinctively. When a missionary enters a new culture, identifying such rules is an essential part of the mission.

Though we are less apt to identify them, the same sort of hidden rules divide the cultures of the middle class and the generationally poor. In their excellent work Bridges Out of Poverty Ruby Payne, Philip DeVol, and Terie Dreussi Smith reveal some of these hidden rules. The differences are too many to list here, but a few give us a flavor. The middle class cares deeply about the quality of their food, whereas in generational poverty, the quantity of food is more important. In generational poverty, who you know and to whom you belong is far more of a status symbol than what you do for a living. Language of the street spoken casually is a more important form of communication in generational poverty than the formal register of the middle class with its linear storytelling. There are many more cultural differences, but just these three examples give us a sense for how difficult even a normal conversation over dinner can be when cultures collide.

This cultural divide matters for a church that desires biblical, socio-economic diversity within its body. James implores the church not to favor the rich over the poor (James 2:1-13). Of course, one of the ways to ensure this does not happen is by not even having the rich and poor interact within the same local body. There is no fear of partiality if everyone is the same. And so we create homogenous units of middle-class churches, poor churches, white churches, black churches, Hispanic churches, old churches, and young churches. If the poor are most comfortable among their own, we reason, let us encourage them to remain separate, because surely that will create a more comfortable atmosphere for the middle class as well. I must admit, it is appealing to spend time with people who are exactly like me. And yet, the New Testament church includes instructions such as those given by James precisely because the church was never intended to separate itself in this way. The gospel of Jesus calls us not to separate for the sake of comfort, but to unify for the sake of proclaiming the message of oneness in Christ. In the gospel, we find the diverse family that cannot be found in the society around us, and that counter-cultural diversity itself is part of the world-changing message of the gospel. Churches that do not care to study the culture of generational poverty will never engage and befriend the poor, and will thus fail to reflect the glory of God’s rich diversity.

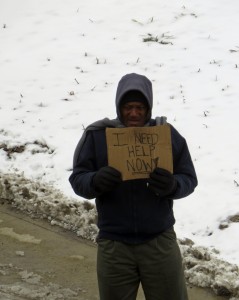

So where do we begin? How does the middle-class church, with its high production values, strong work ethic, emphasis on appearance, and individualistic bent begin to engage, understand, befriend, include, and eventually value the contributions of the generationally poor and their culture? Progress begins with a commitment to creating a church culture where all are loved and valued, and this will need to come first from the middle class, who enjoy the privilege of controlling the resources. Middle-class churches must decide they will not be content with doing ministry for the poor at arm’s length, but will come alongside and live in warm Christian community with poor brothers and sisters within the family of the church. Simply providing material resources for the poor neither creates community, nor breaks the cycle of unsustainable poverty. What will? Relationships! Relationships are the hammer that breaks the cycle.

- Do you identify with the culture of the middle class or the culture of generational poverty? What is one behavior or value from the other culture that confuses you and causes you to be judgmental?

- What is one common practice or value of middle-class church life that might cause someone from generational poverty to feel uncomfortable? How might a church change to help the poor feel included and loved?

Kyle Bushre is the Pastor of Outreach at King Street Church in Chambersburg, Pa. He’s an alumnus of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and a Kern Scholar. Bushre is pursuing a doctor of ministry degree and exploring more effective ways for the church to show compassion.

Read the first post in this series, Generational Poverty.

From the Kern Pastors Network. Image: Aaaarrrrgggghhhh, Flickr.