I am in Hyderabad, India to lead a track on arts and ministry design at the YCL (Young Creative Leaders) conference, and I look forward to sharing my reflections on the conference in the weeks to come. But for now, I’ve reprinted (and slightly revised) a book review that appeared in Comment magazine in 2010. It addresses several of the issues that I have raised with Thomas Kinkade, and it will provide a helpful framework for a future reflections, such as children’s drawings and modern art.

The Challenge

There are few cultural practices more misunderstood and misinterpreted than art. The misunderstanding starts in grade school art classes and is affirmed every step of the way through adulthood. We are taught that art is fun; it is whatever you want it to be; anyone can do it if they really wanted to; and that it expresses your individuality and creativity. What is more, we also learn that professional artists are quirky creative types that don’t quite “fit in” with the rest of us. We are also taught that art is nice decoration to have around but thoroughly unnecessary for daily life, yet that “the arts” are important for our local communities. We are told that even though we don’t know much about art, we know good art when we see it. And perhaps most problematically, we as Christians are told that the art world needs to be transformed, redeemed, and otherwise made safe for the “Christian artist.”

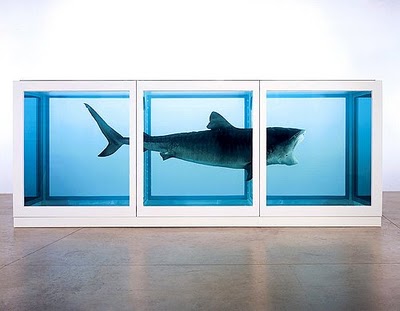

But then we read the newspapers about a controversial artist in London, for example, who uses dead animals, like a shark, and puts them in tanks of formaldehyde, calls them art, and is celebrated as one of the great artists of our generation by scholars with Ph.D.s who write long impenetrable essays in journals few people read. What is worse, someone pays twelve million dollars for it.

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991

What are we to make of this discrepancy between the messages and training we receive as children (and Christians) and what occurs in London, New York, Berlin, and Paris? As Christians, especially those of us shaped by theological traditions that consider cultural practices, like art, to be a response to His life-giving Word, how are we to respond?

We must seek to understand the contemporary art world that values a stuffed shark on its own terms and not fall back upon our romanticized assumptions of what we’ve learned since childhood, which obscures the fact that “art” consists of numerous different and even overlapping “art worlds”—that is, complex frameworks of production and distribution that are essential to the meaning and significance of the work produced in and for it. To interpret the stuffed shark within the framework of the art world into which most of us have been initiated—the art world of fifth-grade craft classes, community arts programs, and Sunday School classes—is to do violence to the stuffed shark and the art world for which it was intended. Art is one of the few cultural practices that seems from the outside not to require significant work, practice, or training to understand. A middle school education seems adequate to recognize, appreciate, and judge it—perhaps even to make it. The problem, however, is that we use our fifth grade craft centers (and Sunday School classes) as the standard to judge all art. As Christians, who take seriously the command to love our neighbors (and our enemies), we fail to realize that the contemporary art world is our neighbor, and loving it means working to understand it, not to rail against or try to change it.

The Art World-A Mysterious and Exotic Tribe

Sarah Thornton’s acclaimed book, Seven Days in the Art World, offers the curious reader access to an insider’s perspective on the art world that values a twelve million dollar stuffed shark and other works of art that don’t look like art. Thornton reveals a very different world of art than most of us are used to. And that is a very good thing. Her book is the result of several years of sociological and ethnographical field research among this mysterious and exotic tribe, learning the language and observing and interpreting their behavior. It is organized around seven high profile art world events that shine a spotlight, in different ways, on the key social roles in this particular art world: the artist, dealer, critic and curator, collector, and auction house expert.

Thornton argues that art is not merely about a particular kind of object or artifact but about social roles, behaviors, means of distribution, and beliefs that make something called “art” possible and through which certain objects and artifacts are experienced and interpreted as meaningful. This sociological approach to art has been given considerable attention by such writers as Jean Duvignaud, Arthur Danto, George Dickie, and Nicholas Wolterstorff, among others. In this context, art is not a qualitative judgment but a particular cultural practice that acquires meaning and significance within a specific institutional framework, which generates a Living Tradition that guides artistic decisions.

Thornton’s narrative revolves around two major themes. Her first, which she reiterates time and again throughout her account, is that “great works do not just arise, they are made.” The art world works to give value to the work of art. And second, she argues that the art world is a secular religion. The contemporary art world, Thornton suggests, “is a loose network of overlapping subcultures held together by a belief in art.” It is not a homogeneous or monolithic institution; it consists of a matrix of communities and institutions that are animated by what Thornton observes, as “a kind of alternative religion for atheists.” Belief holds this peculiar art world together, and belief is mediated through a tradition.

Thornton’s first chapter follows the drama of a public auction at a November sale at Christie’s in New York through the eyes of the auction house’s chief auctioneer, Christopher Burge. Thornton then moves to the other coast to sit in on one of artist Michael Asher’s famous 24-hour “crits,” a distinctive educational event at Cal Arts, one of the nation’s top art schools, in which a group of students explore each other’s work. Thornton then devotes the third chapter to an analysis of the famous summer art fair, Art Basel in Switzerland, where, not surprisingly, she runs into many of the same dealers, collectors, artists, and auction house specialists she had met in New York. In contrast to the tightly run and orchestrated sales at Christie’s, the art fair in Basel is a chaotic gathering of dealers from around the world. The strange relationship between collectors and the dealers is Thornton’s topic, as each jostles for business leverage through the value or perceived value of the art on view. The collectors play the role of the coquette, attracting the attention of dealers and playing them off each other.

Thornton then redirects her focus to the artist through an examination of the Turner Prize, the world’s best-known contemporary art competition, sponsored by the Tate Gallery in London and presided over by the Tate Modern’s venerable director, Sir Nicholas Serota, and a four-member jury. The winner of the Prize has often been controversial, including the maker of the stuffed shark in 1995. Thornton then explores the role of the critic in her chapter entitled “The Magazine,” in which she travels to New York to spend time with Tim Griffin, chief editor, and his colleagues from Artforum, the world’s most respected art magazine. Thornton reveals how seriously the critics associated with the magazine take their roles as interpreters and evaluators of contemporary art. She then travels to Tokyo to visit the studio of Japanese superstar artist Takashi Murakami as the artist prepares for his major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. Thornton presents an artist who is a far cry from the romantic bohemian slacker, making art in isolation and largely unaware of such bourgeois concerns as “business.” Murakami shrewdly presides over a large and complex corporation with dozens of employees. Thornton concludes her narrative with the Venice Biennale, the world’s oldest and most famous international exhibition, in which participating nations present their own exhibitions in special pavilions built by each nation. Thornton profiles former MoMA curator and Dean of the Yale School of Art Robert Storr, the first American-born curator to assume the position of director of the Biennale. Because her account documents the art world at its height, only a few years before the Wall Street crash of October 2008 burst its bubble, Thornton ends her book with a reflection on the implications of the new conditions that now prevail in this art world and her continued fascination with it.

A Christian Response

For those Christians that might think that the Seven Days chronicle degrades or compromises the purity of art and its meaning because she focuses on and celebrates the social structures of the art world and addresses the brut fact that art is a business and big business: it’s time to grow up. Seduced by our fifth-grade art classes, distraught that the church is no longer its primary patron, and armed with a theological aesthetics that dumbs down Beauty, we Christians who want to care about art are usually bitterly disappointed by the art world. But, that is not the art world’s problem; it is ours. Serious art in the western tradition—that is, art that is not content to “image” what we think we already know about the world of appearances and experiences, but probes more deeply into the nature of such reality through aesthetic form–has always been inextricably bound up with business. It is inseparable from patrons and collectors, with markets and dealers, with personalities. It is indistinguishable from all of those aspects that are so easily dismissed by contemporary Christian critics as an alien infestation of modernity, but has been with art all along.

Great art emerges out of the warp and woof—some might say the muck and mire—of commerce, of production and distribution that is at the very heart of Seven Days in the Art World. Can it be any other way? Lives devoted to Christ emerge out of the warp and woof—muck and mire—of nasty church council meetings, contentious denominational conventions, personality conflicts, budget cuts and fundraising, and fights over who’s serving the coffee after the service. This is where and how we must live out our vocations, in and outside the church. And this is how those who participate in this art world must live out their professional callings. The contemporary art world and all its fascinating and irritating mechanizations that Thornton chronicles deserves a robust and thick sociological analysis from a Christian perspective, not hand wringing and condemnation because such a structure fails to conform to our distorted fifth grade ideals, which fails to recognize that the art world operates not within God’s right-handed reign with the church but his merciful left-hand governance in the world.

Throughout her account, she observes that this art world functions as a religion for many of the participants. This should interest us. For even though the art world must be understood on its own terms as a secular practice, the posture of the human being is always faith, and so faith directed toward the Word fully actualizes a secular calling like art. As Martin Luther provocatively and insightfully suggested in “The Disputation Concerning Man” (1536), Rom. 3: 28 (“justified by faith”) is the ontological definition of the human being. As means for the human being to justify him or herself, to achieve recognition, both art and religion are closely aligned and have no peers.

Thornton’s observation that the contemporary art world requires faith, opens up productive space for Christian reflection on contemporary art that addresses the complex, convoluted, and opaque institutional framework that institutionalizes the human need for justification by faith. Yet, despite the fact that the art world generates such aesthetic self-justifications (idols), it also produces works of art that incomprehensibly, inexplicably point toward an alien presence in the world, a hint, a faint echo, a sweet aroma from beyond the hills that testifies to God’s promises that all will be well. As a result, the contemporary art world is littered with altars to the Unknown God (Acts 17). Our responsibilities as Christians are to roll up our sleeves and engage this world which Thornton presents, resisting the self-righteous temptation to judge it according to some romantic misconceptions that presuppose that it needs to be transformed to reflect our own idolatries. We must instead creatively and imaginately engage and name those altars as a means to preach the justifying grace of Christ at work in the world—even in a part of that world in which a stuffed shark is art.