Proper 24 — Job 38 — Year B

Earlier this month, a gunman went on a shooting rampage at a community college in Oregon, millions of Syrian refugees fled a bloody civil war where thousands have been killed, and we were reminded again that there have been more gun deaths in the United States since 1968 than in all U.S. wars combined.

These are all sobering facts.

But it is also true that we are living in the most peaceful and least violent time in human history.

Just like it is true that hunger and hunger-related diseases kill 21,000 people every day and that 1 in 6 don’t have enough to eat worldwide AND it is also true that fewer people are hungry than ever before, that through political advocacy and charity, the number of people suffering from hunger around the globe has been cut in half since the 1960s.

From one perspective, the world is on fire with suffering and violence. From another, it is being healed and we are making progress. And it can be hard to hold both truths in your head much less your soul.

But both are true and each has its own wisdom and gift for our life of faith, and that I think, is the paradox of a book like Job, a book of immeasurable tragedy and suffering and of the most extraordinary and beautiful poetry in all of Scripture.

In today’s reading, we only get a small taste of the beauty in God’s response to Job. And, if I’m honest, it’s seems at first glance to be an incredibly odd and bewildering response to Job’s searing inquisition of God and to his painful suffering. A few chapters prior to this, Job had taken up his case against God and demanded a hearing. In a very real sense, Job is putting God on trial. He’s indicting God for crimes against humanity via divine of indifference.

And who can blame him? His children have been killed, his body afflicted with leprosy and boils, and he has become an impoverished beggar. Job looks around the world and sees it as a dangerous place, full of hard, sharp edges that cut at both the body and the soul. The world has become a place of hopelessness and all Job can see is its ugliness and suffering. After the wounds of loss and grief, it’s understandable. In fact, Job’s anger is a deep, primal form of faith. Imagine the kind of faith it takes to trust God enough to condemn God.

In essence, Job is asking where in the world God has gone as he looks around at the suffering. Job demands to know why has God so forsaken humanity.

While Job’s friends attempt to shush what they perceive as his blasphemy and heresy in the raw honesty of suffering, God doesn’t condemn Job. Rather, God condemns Job’s friends. Job’s reputation of being righteous and blameless continues not in spite of his doubt and questioning of God but because of it.

But God does respond to Job’s indictment.

God just doesn’t give him an answer. God doesn’t try to explain it. God doesn’t even contradict Job’s accusations.

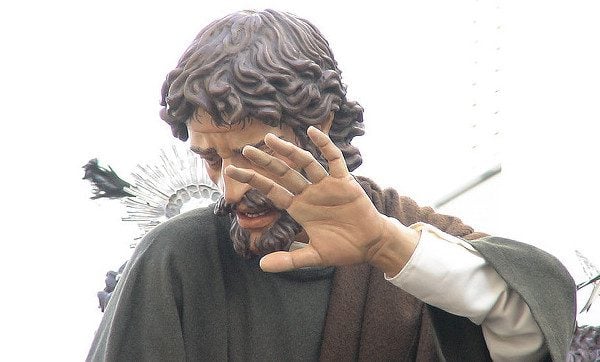

Instead, God responds with beauty.

Job cast a vision of a world overshadowed by pain and suffering. God responds by showing him the beauty and hope of the same world.

And here’s the thing. I’m not sure these are competing views. I don’t think the one negates the other. God doesn’t respond with beauty to cancel out or disregard Job’s suffering. I think that’s why God doesn’t exactly answer Job’s question about suffering. Because no answer — even one from God — is ever satisfactory in the midst of our pain and grief. Nothing solves suffering. Nothing answers it. But neither is suffering and grief the whole story of our lives and of the world. There is beauty, and grace, and hope in the world, too, existing simultaneously, in paradox, side-by-side.

For most of my life, God’s response to Job in this book has frustrated me, even angered me. It all seemed so insufficient a response. But now I can’t help but wonder if there is wisdom in responding to suffering with an invitation to see beauty around us, to allow beauty to interrupt despair and grief.

Like suffering, beauty cannot really be explained. Like suffering, beauty can only really be experienced. And like suffering, beauty changes us. For Job, suffering and grief removed the protective barrier of wealth and privilege and opened his eyes to see how deeply suffering, injustice and pain are shot through the human experience. So much so that all he could see was pain and suffering in the world. In a similar way, the more we experience and observe beauty, the more frequently we experience it even in small and unexpected places, in the way a sleeping child tucks her hands under her cheeks at night, the way a spouse tilts his head back in laughter, the pirouettes of a single yellow leaf falling from an empty tree.

But we need both. We need to cultivate both, an awareness of the suffering of humanity and an awareness of the beauty of the creation. We need to experience both the remote absence of God and the divine immanence of a God who is with us in creation.

Because both are true to our lived experience.

Just as Job is pleading with God to look at the world and bear witness to its suffering and pain, God is pleading with Job to look at the world and bear witness to its beauty and glory.

And I think they need each other in this story, to learn from the wisdom and experience each offers to the other. God needs to see Job’s prophetic grief. Job needs to see God’s prophetic beauty. If all we experience is prophetic grief like Job, we can spiral into despair, paralyzed by the overwhelming nature of the earth’s suffering. But if all we see is prophetic beauty, we can spiral into lofty ideals and become so detached from the reality of human pain that we become just as paralyzed.

Both are incomplete without the other. Job is trying desperately to draw God’s eyes to the plight of humanity, and God is trying desperately to draw Job’s eyes beyond humanity and suffering and to the larger world around.

Humanity needs the rapturous divine, and the rapturous divine needs the gritty realities of humanity.

That’s the change we see in the book of Job in the end.

God and Job finally see each other, eye to eye.

At the beginning Job and God are far removed from one another. In the heavenly court, God appears to be a distant observer, considering his servant Job from afar. For Job, God is a distant provider, showering wealth and blessings upon him. God is so far removed from Earth that God seems to view Satan with suspicion because of all the time the Adversary spent traveling the earthly lands.

But by the time the book ends, things have changed. The divine courtroom, where God and Satan wagered, has been replaced by an earthly one where Job and God argue. And the picture we see of God is not of a removed being but of a God who is intimately involved in and present in every corner of the earth from the most insignificant creatures to the most massive ones. God has become integrated with creation before Job’s eyes.

God is no longer above humanity, but alongside, so much so that Job can say, “Before I had only heard about God. Now I have seen God.”

Beauty and suffering held in tension, a dance between the divine and the human, the rapturous beauty and the constant wounding, a courtroom argument between God and humanity in which neither loses and both discover what they had been missing.

And so that is my challenge to you today, to cultivate an awareness of human suffering and to cultivate an awareness of beauty in the world. Because I think in the place where those two meet is the place where we just might find Jesus — the fullness of God’s glory experiencing the depth of human suffering — hard at work in the world.

Photo Credit by Martin/Flickr