A few weeks ago, a longtime reader, a gay man in his 60s – his age, as we’ll soon see, is relevant – PM’d me on Facebook and charged me with high treason. To credit him with realism and flexibility, he had not expected me to support any particular cause. But, in my piece accusing the Church of pastoral helplessness vis-a-vis transgender people, I had used a word that, in his judgment, had belittled him, and exalted myself, unforgivably. Here was the incriminating passage:

G.K. Chesterton once griped about “the modern and morbid habit of always sacrificing the normal to the abnormal.” Well, now that we’re in post-modernity, any concept of normal is thought to be the tribute that privilege pays to itself. If we normal folks go on pretending we’re the only ones here, we’ll be sacrificing our own credibility.

For want of some scare quotes, a friendship was lost. If that particular piece had been less analytical and more confessional – that is, if I’d been writing more in my own voice, less in a standard editorial voice – I would never have numbered myself among the normal.

One theme I return to frequently is the task of having to find or create value and meaning in the truncated life that my various failures have obliged me to lead. Failure isn’t something people talk much about, except to make it the low point in a story of triumph or redemption. Though, doubtless, such stories have the power to cheer people up, I don’t know that they’re always very true to life. Past a certain point, I think, many of us have no choice but to look around and say, “These are the options I have. They may not amount to much, but I still have to make the most of them.”

One thing I’ve hesitated to do is dissect the reasons why I failed as a grad student, as a loan officer; why teaching EFL drove me nearly out of my mind; why I only perform adequately in low-status jobs demanding little in the way of initiative. The reason is deeply embarrassing: I can’t think straight. No pun intended. That is, I can’t assimilate new information quickly, can’t produce new words in great volume or at great speed. When I was an undergrad, this was no problem, as the light workload enabled me to take as much care as I needed with every assignment. Entering grad school felt like limping onto the San Diego Freeway in an underpowered Geo Prizm, so I limped off again.

Being disqualified from the professions wouldn’t be so bad if I had a knack for tinkering with engines or writing code, or even dealing with people. No such luck. (People are, for me, the most impenetrable mystery of all.) So I write press releases for an SEO agency. I rent, get around by bike – though a fairly high-end road bike; I like to go fast – and buy my groceries at Wal-Mart. Every day I thank God for helping me land on the tail end of the creative class. Rents are rising, however, and I would not be too surprised to find myself out on the street within a year or two.

Now, it could be that I’m just not very bright. But, given my standardized test scores, I think it’s likelier that something’s preventing my brain from doing what it’s otherwise fairly capable of doing. What that might be I have no idea. No description of any disease — or disorder, or syndrome – has ever jumped out and shouted, “Baby, it’s YOU!” A few times, I did set aside hard-won personal prejudice – if you’d grown up in a Freudian household, trust me, you’d turn your headspace into North Korea the first chance you got – and sought professional help. The only satisfaction I obtained came from realizing I had as firm a grasp on my brain’s secrets as the experts.

The Church teaches that every human person has an inherent dignity. It also teaches that happiness comes through the exercise of virtue, or, as Zoolander would put it, results from doing stuff good. Discovering and applying the two teachings gave me a useful new perspective on my life. On one hand, I was perfectly justified in fretting over not doing stuff good. On the other, whatever I’d lost, or couldn’t afford, I still possessed dignity. That might not sound quite warm or fuzzy enough to qualify as an affirmation, but it did inspire me to quit drinking and dabbling in drugs, and all the other things people do once they’ve decided they’ve dipped beneath anyone’s consideration, including their own.

Analogies can deepen understanding, and I got into the habit of understanding my own predicament by comparing it to those of gays and lesbians. The analogy wasn’t exact: in Church terms, they had “a more or less strong tendency toward a grave moral evil,” whereas I was simply unable to do much good very consistently. But one more thing we had in common, it seemed to me, was the particular brand of self-loathing that comes from failing to fulfill the calling of our sexes. Most of them were not enough attracted to the opposite sex to marry and start families. My inability to earn a decent living made me, in effect, a natural celibate.

Please don’t imagine that I ever had the effrontery to identify with gays and lesbians. They faced problems completely outside my experience. (Physical danger and harassment weren’t, however, among them. I live in a high-crime area, on a street where any solo pedestrian, male or female, runs the risk of being mistaken for a prostie.) After working so diligently to make themselves respectable in the public eye, they needed straight fringe characters drinking on their tab like they needed a hole in the head. Conversely, believing that I was mismade in a way analogous to members of a group boasting so many certified geniuses, fit like a pad under the cross I had to bear.

So, no — I would not say to my angry ex-reader that I feel his pain. But it may yet be that I have more in common with him than he has with some of the young bloods just now coming up. Even before Obergefell granted gay couples nationwide the right to marry, gays were putting as much daylight between themselves and their underdog status as they could manage to do. J. Bryan Lowther notes that some gays have quit calling themselves gay – a label they find undignified for its association with a particular cultural ghetto.

Even some of the older guard are copping to snobberies with a new boldness. Alexander Chee writes that the gay hero of a futuristic novel might plausibly belong to “an elite group of wealthy gay men…residing in an intentional community sexually sealed off from anyone who can’t pass a credit check and an HIV test.”

Who, really, can blame them? It’s one thing to romanticize life on the margins if you’ve nowhere else to go. But anyone with options should recognize it for what it is: a dingy, depressing, precarious, pain-in-the-ass existence. Absent a genuine conversion or rocks in the head, there’s no reason any gay or lesbian should choose the abstract dignity and happiness offered by Church teachings to the tangible joys of the American dream (or what remains of it). It’s no skin off my teeth — I have, I hope, grown spiritually to the point where I can understand myself without recourse to rough comparisons.

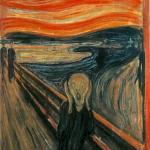

I’m not sure whether my ex-reader, at his age, is able to adjust to his new legal status as first-class citizen (and cultural status as 800-lb gorilla). But if he’s too set in his ways – if the old guilt and self-doubt remain caked on like so much sediment – he should know he’s not alone. I’ll still be here, living the abnormal life.