There was a recent news report, perhaps you’ve seen it, that Scandinavian countries are seriously considering a ban on ritual circumcision. The Huffington Post reported:

There was a recent news report, perhaps you’ve seen it, that Scandinavian countries are seriously considering a ban on ritual circumcision. The Huffington Post reported:

In September 2013, the Child Rights International Network released a joint statement from the Nordic Ombudsmen for children and pediatric experts which said, “As Ombudsmen for Children and pediatric experts we are of the opinion that circumcision without medical indication is in conflict with Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which addresses the child’s right to express his/her own views in all matters concerning him/her, and Article 24, point 3, which states that children must be protected against traditional practices that may be prejudicial to their health.” It was signed by representatives from Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Greenland.

Christian critics are especially concerned that this move will eventually eliminate or at the very least severely diminish the Jewish and Muslim ethnic populations in Scandinavia. Mark Movsesian over at First Things writes:

To put it mildly, a ban on the non-therapeutic circumcision of boys would cause some hardship for Jews and Muslims. At the very least, parents who wished to have their sons circumcised for religious purposes would need to have the circumcisions performed outside their countries—assuming a ban on circumcisions would not also prohibit parents from transporting children for such purposes. Most likely, a ban would simply cause Jews and Muslims to leave Scandinavia in large numbers. In fact, opponents of the ban allege that is its goal.

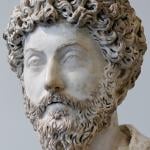

This report got me thinking about the ban on circumcision in the church of Augustine and Jerome in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. You might remember that these two giants got into an interpretive dust up over the practice of the Mosaic Law among Jewish believers: Paul, Peter, James and John. The debate was in response to Jerome’s Galatians commentary which Augustine read. On the one side, Jerome believed that all the apostles agreed that the doing of the law for either Jew or Gentile was “hurtful and fatal” and that neither of the two men in the Antioch Incident Peter or Paul actually believed that doing the law was acceptable. According to Jerome Peter was just pretending to follow Jewish customs for the sake of reaching the Jews. And Paul went along with the theatrics. Rather they were “pretending” so that they might not bruise the conscience of Jewish Christians. In his response to Augustine, Jerome says of a person maintaining Jewish practices and at the same time believing in the Jesus:

But while they desire to be both Jews and Christians, they are neither one or the other. (NPNF 1, 338)

Augustine, on the other side, protested against the intentional deception of the apostles on the grounds of biblical inspiration. And instead argued that at that time in the progress of the Gospel, it was acceptable and indeed appropriate for Jewish believers to practice the Mosaic Law as long as they did not see it as a necessity for salvation and did not compel others to follow the Law, either Jew or Gentile. As long as it was for the honor of the tradition that God had given in the Old Testament, the foreshadow of the grace to come, it was appropriate for Jewish believers to practice the Law. Augustine believed both Peter and Paul practiced the law. This fascinating debate can be followed easily in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series 1, volume 1 edited by Schaff. Look them up here, here, here, and here.

What is interesting however is that while they disagreed over the early Christians, they agreed on the issue of Jewish practice in the church in their own time, the the early 5th century. Here Augustine summarizes their shared view in a letter to Jerome (the final in the series of communication on this issue):

For now, when the faith had come, which, previously foreshadowed by these ceremonies, was revealed after the death and resurrection of the Lord, they became, so far as their office was concerned, defunct. But just as it is seemly that the bodies of the deceased be carried honourably to the grave by their kindred, so was it fitting that these rites should be removed in a manner worthy of their origin and history, and this not with pretense of respect, but as a religious duty, instead of bing forsaken at once, or cast forth to be torn in pieces by the reproaches of their enemies, as by the teeth of dogs. To carry the illustration further, if now any Christian (though he may have been converted from Judaism) were proposing to imitate the apostles in observance of these ceremonies, like one who disturbs the ashes of those who rest, he would be not piously preforming his part in the obsequies [funeral services], but impiously violating the sepulcher . . .

And I now, as speaking in the sight of God, beseech you by the law of charity to believe me when I say with my whole heart, that it never was my opinion that in our time, Jews who become Christians were either required or at liberty to observe in any manner, or form any motive whatever, the ceremonies of the ancient dispensation; although I have always held, in regard to the Apostle Paul, the opinion which you call in question, from that time that I became acquainted with his writings . . . Jewish ceremonies are to Christians both hurtful and fatal, and that whoever observes them, where he was originally Jew or Gentile, is on his way to the pit of perdition, I entirely indorse that statement, and add to it, “Whoever observes these ceremonies, whether he was originally Jew or Gentile, is on his way to the pit of perdition not only if he is sincerely observing them, but also if he is observing them with dissimulation”. (NPNF 1, 355-56)

Augustine and Jerome placed a ban on circumcision in the church. A ban that continues today in the pervasive supersesessionistic theology of our church. It seems the largely Gentile church today needs seriously to consider how multi-ethnic it has been and now wishes to be in the 21st century. The Christian tradition has little high ground on which to stand when it comes to the issue of banning Jewish practices. Do you think these two giants of the Christian tradition were correct in their conclusions about Jewish and Christian identity? What would the church be like today if Augustine didn’t agree with Jerome? Interesting questions to ponder.