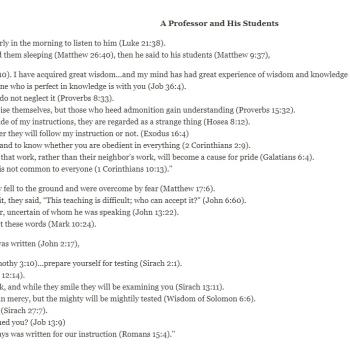

Matt Emerson wrote a blog post about source criticism, much of which he finds problematic. The post concludes with the following questions:

First, if the 1) methods, 2) assumptions, 3) conclusions, and 4)philosophical underpinnings of the seminal works for both of these theories are questioned by virtually all contemporary biblical scholarship, why do we still refer to them as if they represent scholarly consensus or as if they are the only way to understand the composition of the Pentateuch and Former Prophets?

Second, how can any non-confessional scholar look an evangelical in the eye and claim objectivity of method and conclusion when a) neutral objectivity is an Enlightenment myth and b) the supposedly objective methods and conclusions are claimed by their own peers to be arbitrary and contradictory?

One final comment: I named this post “The Silliness of (Some) Source Criticism” because I do not want to suggest that source criticism is of no value. It does have value. But when it is appropriated and used in service of “objectivity” and German philosophy, and then left to its own devices by subsequent scholarship, it devolves into self-contradictory silliness.

I don’t know anyone who thinks that source criticism is the only way to approach the Pentateuch, and I haven’t encountered anyone who suggested that at any point in my lifetime. By the time I was first getting started as an undergraduate, literary approaches which focus on the final form were already commonplace.

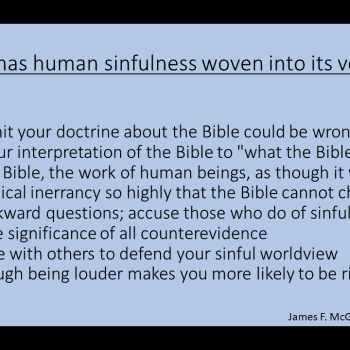

I also don’t know anyone who would claim that scholarly methods provide objectivity. What they provide is a useful counterbalance to our biases, a way to try not to simply read in ways that are so shaped by our assumptions that the evidence cannot challenge us to draw unexpected conclusions. And many of us reject both the modernist assumption that certainty is attainable and the postmodern assumption that everything is just bias and nothing else, seeking a middle ground, a critical realist approach, which is chastened by postmodern critique and yet finds it worth trying to see beyond the framework of our biases, even if the attempt can never be completely successful. It is rather like learning a new language as an adult – it may be impossible to ever speak so perfectly and with such precise pronunciation as to be indistinguishable from a native speaker. But that doesn’t mean that it is not worth trying, nor that the attempt cannot bring us closer to that out-of-reach goal than we would ever come by simply dismissing it as an impossibility.

There is, I think, a certain irony about Emerson’s post, which frames the discussion in precisely the sort of modernist terms that some confessional approaches still favor – seeking absolute certainty even when the sources and methods cannot provide it – while complaining that mainstream scholarship is allegedly doing that.

But I think the question of why source criticism remains so useful – despite it having emerged on the basis of problematic assumptions, and having been applied in problematic ways – is a good one.

The short answer is that source criticism itself – like many other developments in other academic fields – is separable from the cultural and philosophical context that gave birth to it, and even more importantly, it makes good sense of the data. We may not be able to precisely delineate sources in the manner that the Enlightenment project hoped to. But that does not mean that source criticism ceases to make better sense of the differences between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 than an approach which regards them as the work of a single author. So too with the view that Deuteronomy has a separate origin from other pentateuchal material.

Perhaps one can make a useful comparison with evolutionary biology. There is – and will probably always be – debate and discussion about a wide array of details, and new discoveries can require the revision of longstanding assumptions. But the overall framework of evolution – even in today’s context in which the practice of science is very different than it was in the 19th century – still fits the evidence so well that there is consensus about the big picture, even as small details of that picture are capable of more than one interpretation.