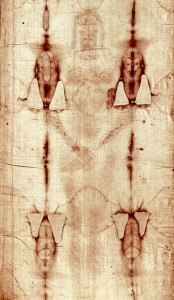

If you asked me about the Shroud of Turin, I could speak for hours. Before I saw it in Italy one Easter, I read several books on it. So I could tell you the Shroud is a linen cloth, three feet wide and fourteen long, that’s marked with faint front and back images—like those of a sepia photo—of a man in burial pose.

Beginning at one end of the fabric and panning lengthwise towards the other, you can see the front of the man’s body: his ankles, shins, knees, and thighs; his hands shielding his groin; his stomach, chest, beard, and face; his tendriled forehead at mid-length.

From there, continuing on, you can see the man’s back: his hair gathered in a ponytail at the nape of his neck; his shoulders, buttocks, hams, and calves; his heels at the far hem.

You suspect the man’s been scourged. Blood-filled back and buttock wounds bring to mind flagellation by a leather multi-thonged whip, lead pellets tied to tips. Blood-crusted wrist and ankle wounds suggest an ancient crucifixion, iron nail shafts rammed though flesh and bone by pounding rough-hewn heads.

You theorize the man’s been crowned with brambles. Blood has trickled through his locks from myriad scalp and forehead punctures. You surmise the man’s been speared. Serum has puddled at his waist from a right-rib, lance-shaped wound.

So you guess, if you’ve read the Gospels, that the Shroud is Jesus’ burial cloth, the sudarium John and Peter found in their teacher’s vacant tomb. And you grasp why it’s the world’s most-guarded relic—displayed only once each twenty years—and why scholars debate its authenticity, some proclaiming it a miracle, others declaring it a fake.

If you asked me about the Shroud of Turin, I could summarize its history. Some experts place it in Jerusalem in AD 33 and chronicle an almost gapless jaunt:

To Edessa in AD 34, where Christians hid it from vandals in the city’s stone surrounding walls, to Constantinople in AD 944, where the Byzantine emperor raised it banner-like in his palace church.

To Athens, Greece, in AD 1204, when Fourth Crusaders sailed into Byzantium and seized it with the empire’s Christian relics, to Lirey, France, in 1354, when a French knight took it for himself.

To Savoy, France, in 1453, when the knight’s heiress gave it to a duke in exchange for a country castle, to Chambéry in 1502, where the duke placed it in his royal chapel behind an iron grill.

There, the cloth remained, folded in a bolted, silver coffer, until a fire swept the chapel in 1532. Hell-bent to save the Shroud, two Franciscans doused the reliquary, summoned a smith to pry the hasps, unfurled and inspected the Shroud.

Melted silver had singed a folded corner. Water had seeped through the fibers. But except for a series of scorch marks burned through to holes at intervals, the image was unmarred, and Poor Clare nuns patched up the holes.

Then, in 1578, Milan’s cardinal planned a pilgrimage to the Shroud, so the cloth was moved to Turin, Italy, to spare him a hike across the Alps. Today, the Shroud remains in Turin’s Duomo, out-of-sight for decades at a time, in an airtight, bulletproof case.

If you asked me about the Shroud of Turin, I could recount the scholarly debates. Despite the propositions of their colleagues, some historians dispute the Shroud’s existence before its debut in medieval France.

Radiologists endorse the naysayers—their carbon-14 studies date the cloth to the early 1300s; they claim the image and bloodstains are paint, a counterfeiter’s work. Forensic scientists support the yaysayers—they find no pigments on the fibers, just human blood and serum; they charge the radiologists with sampling a Poor Clare patch.

Textile experts back the devotees—they say the Shroud’s herringbone weave was prized in Caesar’s time and unused in the Middle Ages. Botanists agree with them—they say the Shroud is strewn with flower prints and pollen from Israeli mums extinct before medieval times.

But the nonbelievers are diehards, determined to prove the Shroud a fraud by reproducing it themselves: They’ve tried Byzantine tempera painting, medieval photography, printing bas-reliefs. They’ve attempted hot statue wrapping, line engraving, and vapography. They’ve tried fungal and bacterial methods, non-enzymatic browning, singlet oxygen techniques. They’ve undertaken fabric scorching, flash irradiation, and electrostatic fields.

Then came an aero-optics expert who thought he’d proved the Shroud authentic, settling the debate: his NASA image analyzer showed the Shroud plots a 3-D elevation of a tortured human male. But skepticism persists, although no technology we know of—no natural process, no artistic or photographic method—can make an image like the Shroud’s, one that plots 3-D.

So if you asked me about the Shroud of Turin, I’d have plenty to say.

But most of it is straw.

Because there’s something that leaves me speechless, something I didn’t read in books, something that didn’t strike me till I stood in the dark cathedral among a praying crowd and stared at the backlit Shroud suspended on a wall before me, so close I could have touched its fibers, the imprint, the blood.

That something is this: Jesus was a man, a man no bigger than my son, one man among the billions who have lived or ever will. And one spring evening long ago, he pulled his hair into a ponytail to prepare bread and wine for his disciples, as my son pulls on a favorite t-shirt to set out beer and nachos for his friends.

As if it were an ordinary evening.

But it wasn’t an ordinary evening; it was the last one of his life.

And when his mother saw his broken corpse, one she hoped to never see—as I hope to never see my son’s—she tossed a few chrysanthemums upon it, covered it with the Shroud, and left the tomb with her grief.

Then, when all was quiet, a flash of light, a flutter of fabric. An image to hold onto until eternity.

Jan Vallone is the author of the memoir Pieces of Someday: One Woman’s Search for Meaning in Lawyering Family, Italy, Church, and a Tiny Jewish High School, which was released in December, 2013, and has won the Reader Views Reviewers’ Choice Award. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Good Letters, Faith & Values in the Public Square, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, and Writing it Real. She teaches writing and literature at Seattle Pacific University.