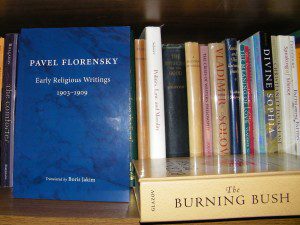

Pavel Florensky. Early Religious Writings: 1903 – 1909. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdman’s Publications, 2017),228 +xiii pages.

Pavel Florensky, perhaps the most poetic and beautiful theological stylist of the Russian Silver Age, has within the last couple decades become much more known and recognized for his greatness by a Western audience. His greatest work, Pillar and Ground of the Truth, also translated by Boris Jakim, should be the first of his works which interested readers should pick up and read. It can be seen as the cumulation of Florensky’s theological investigation up to the point of its writing; what came before it, such as the essays and texts found in this book, helps provide the supplemental reading which complements the themes addressed in Pillar and Ground of the Truth.

A significant belief which Florensky explains, both in Pillar and in the essays collected in Early Writings is that theological investigation should be based upon and explore authentic religious experience. It is not just an intellectual game. We must not misconstrue the teachings of the faith as mere ideas which we must hold on to, but rather, they must be seen as expressions of the truth, truth which accords with experience and leads to authentic religious praxis. Dogma, as Florensky explained in his essay, “Dogmatism and Dogmatics,” is important, but it is like the scaffolding of a structure still under construction. It brings together what has been experienced and established in the past, making sure the building is made upright and stable, but it must not be seen as the final product of that building itself. “To be sure, it does not follow that we do not have the right to use anything except that which is directly observed in the spirit. We have every right to be guided by ready-made schemata, but they must only be used as a preliminary scaffolding that allows a more rapid and efficient processing of the raw material” (134). The spiritual life, the experience of the Christian life, the questions and reflections which develop from that experience, all of these must unite together so that the truth of Christ can shine throughout the world. It must be a living faith, not a dead construction.

This collection of essays can be seen as similar scaffolding for Florensky’s greater theological work. It provides his observations and experiences. There is much in it that can be said to be phenomenological, such as his attempt to redefine superstition in “Superstition and Miracle” as that way of viewing and using the dark, occult forces which underlie and guide the world, in contrast to a religious view, which engages the world through holiness and what is right, and a scientific view, which is rationalistic and empirical in its assessment of the world. In this manner, superstition is said to look for and engage the dark, diabolical ways of controlling and manipulating the world – often started by someone who is at first interested in their existence, exploring them for insight into the world, only to be enchanted by the darkness and embrace it for themselves.

In “The Empyrean and the Empirical: A Dialogue,” the modality of experience is further discussed, showing how and why those coming to discuss the Christian faith through positivism might be able to systematize their rejection, but they will be doing so in a way which does not truly engage or discuss the Christian faith itself: it only sees and encounters the exterior form of Christianity without understanding the core spirit within, similar to the way sacraments, when judged from their physical form, will not reveal their essence, but when encountered, can be seen to have real positive effects which transcend empirical understanding. Florensky, likewise, addressed where he believed the confusion emerged: in the distinction between empirical “naturalism” which has no spirit to it, nothing beyond the external form which is encountered, and a symbolic understanding of the world, which understands further layers of meaning beyond such externals are possible, even if we encounter them in and through such forms which the empiricist recognizes. That is, the symbolist is capable of recognizing the transcendent and to see and experience it in and through the material form, because they do not close meaning to that empirical form alone. This is why the symbolist is able to encounter and experience new and greater layers of meaning, and so see and encounter a more in-depth form of reality, because they are not attached to the externals as empiricists have to be: “Objects of the religious worldview are therefore more full-bodied and richer than positivistic ones. The former can be compared to chords, but the latter to separate notes” (55).

This interest in religious knowledge and experience led Florensky to ask readers of an Orthodox magazine which he wrote for to relate their experiences of the sacraments, to see if those who partake of them could demonstrate a phenomenological shift in and through their reception; the answers, collected in “Questions of Religious Self-Knowledge” will unlikely satisfy any skeptic but they do demonstrate the kind of engagement Florensky was interested in his own theological investigation. He wanted lived experiences to serve as validation of religious wisdom and teaching; he knew those experiences could always be disputed by outsiders, but that is not their point; the experiences give meaning to those who have them, so that their own theologizing and philosophical inquiries do not end up mere being intellectual games investigating subjects with no content.

It is for this reason Florensky also wrote spiritual biographies, first of Archimandrite Serapion Mashkin in “The Prize of Higher Calling,” and then of Abba Isidore in “The Salt of the Earth.” Both of these biographies served to demonstrate the experiences of those who encountered the spiritual world and lived out that experience, sharing with others, the fruit of their experience. Pure hearted sincerity and love gave them a higher perception of reality. Through the transformation which they experienced, they were made to seem and appear different to others – not just eccentric, but often foolish and yet their foolishness was a wisdom which transcended ordinary human knowledge. For those who have an open heart, the purity of heart found in spirit-filled individuals are attractive. What can be seem odd or troubling about potential saints ultimately serve to reveal some hidden truth, and only those who are ready to see and encounter that truth will be given the full understanding of the mystery which lies out in the open when someone encounters a holy person in their life. They themselves understood this, as Florensky demonstrated in the story of Abba Isidore’s famous “ascetic jelly” which was given only to special people who he knew were ready to appreciate it: in the earthly sense, they jelly was bitter and unsatisfying in taste, but for Isidore and those who saw the world in his light, such jelly was actually a delight, a means of partaking the glory of God on earth. “There were reasons for this: those who were not properly trained could barely swallow a single spoonful of this ascetic jam. Father Isidore, on the other hand, would eat several spoonfuls and praise it” (171). This was all in part a demonstration of how the conventions of the world are overcome and subverted by the transcendent experience of the spirit, and those without that spirit will not be able to discern and engage the glory before them, but those who are, will see all things and enjoy things in the spirit as a gift of God. This is the kind of life of prayer which empties itself of presumption and so is able to be lifted up from the scaffolding of dogma and into an encounter with the truth itself. This is what Florensky aimed for in much of his theology. While Florensky would discuss the dogmas of the faith, explaining their significance and relevance, he would not end there: he would remind his readers that what is under discussion is not merely the matter of intellectual dispute but the experience of the Christian life, and without that experience, the theologizing ends up dry and unattractive, like many of the dogmatic manuals which were in vogue in the nineteenth century.

This is what motivates his essay, “Orthodoxy,” which is an exploration of the experience and beliefs of the ordinary Russian Orthodox believer (and so is not meant to be seen as a representation of the whole of Orthodoxy itself). He suggested that in the development of the Russian Orthodox faith of the ordinary peasant, the believers inherited a theological system and dogmatics from Byzantium, and added to it the basic, spiritual principles established in their own nature-oriented religion which they inherited from their pagan backgrounds. Such paganism, he believed, was never entirely abandoned by the Russian peasants but remained side by side with the higher theological system: nature spirits were to be appeased in daily life, even as they opened up to God in a liturgical setting, which to them, was more important than the morality and theologizing of other Christian lands: “Another aspect of the Orthodox relation to the church is the tendency to emphasize cult, especially ritual, instead of doctrine and morality. Quarrels, fights, drunkenness are lesser sins than the violation of fasting; violation of chastity is more easily forgiven than the failure to attend church services; the participation in the liturgy is more salvific than the reading of the Bible; the performance of the cult is more important than charitable giving” (149). In his exposition, Florensky highlighted both the strengths and weaknesses of this system, so that it was not a mere romantic engagement with their simple beliefs. What they inherited had much which could be said to be good, but many of those pagan roots could also be seen as giving some negativity to the faith as well, so that superstition could remain. Yet, what was important and invaluable was the way grace penetrated the minds of the peasants, so that they lived it out in how they treated each other. Moralism and dogmatism did not get the upper hand. Thus, in Russia, the peasant, the lowly, the ignorant, the tattered poor, could be seen truly as representatives of God more than the super-men of Nietzsche and Western Europe: “if God himself came in a powerless and humble form, how can we despise powerlessness and humility? Perhaps, grace is revealed precisely in what is powerless and humble? Therefore, Orthodox believers never judge by appearances. They are in no hurry to be outraged and condemn; inwardly, they even sympathize with the drunk, the poor, the tattered, the ignorant, and the outright foolish” (158). Holy fools who overturned all conventions, who were humble and lowly, imitated the kenosis of God in Jesus and showed forth the radiance of glory more than the pseudo-glory of earthly achievements. This, once again, highlights what can be seen as what connects the essays in this book: only by a new vision of reality, a new vision of the world, where the ordinary ways of grasping the world are overturned, can we truly see God in all things and receive the glory which is already there before us.

As with any work by Pavel Florensky, or any of the translations by Boris Jakim, who has provided a wonderful service to English speakers everywhere with his English language editions of the classics of the Russian Silver Age, I would give my enthusiastic recommendation for anyone to buy and read this book. Certainly, as it is a collection of essays, some texts in it are more interesting than others, but together as a whole they provide key insights which are worthy reminders to those living today of how far off we have strayed from the spiritual path and what kind of vision we need if we truly want to engage any God talk at all.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing