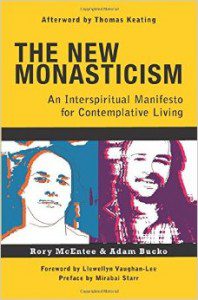

I recently read Rory McEntee and Adam Bucko’s The New Monasticism: An Interspiritual Manifesto for Contemplative Living. As a scholar of Spiritual Ecology writing a dissertation on the ways that Catholic monastics manage and relate to land, I have had my eyes on the New Monastics and their claim to be adapting to what many are calling a Second Axial Age—an emerging Inter-spiritual revolution that is resulting from the globalization of consciousness. I have tremendous respect for both authors, their amazing work, commitment to social justice and their ongoing contributions to conversations on this emerging spirituality. Like the authors, I too grew up on the edge of generation X and the Millennials, was raised in a traditional religious context, and in my 20s branched out into a wider-reaching Inter-spiritual path. Like the authors I too have felt a strong sense that something new is happening in the world of religion and spirituality that cannot be contained within existing religious institutions.

The authors take readers on a thorough tour of this emerging spirituality and its roots in contemplative and monastic practices from several religious traditions, namely Christianity and Hinduism, but also including Islam, Judaism and Buddhism. The authors are clear that they not New Age syncretists taking a buffet approach to religion in the service of self-realization. They are serious about deep connection to God and the world, and the intentional transformation of both self and world through rigorous spiritual practice. They see the growing numbers of those who identify as ‘spiritual but not religious’ as an authentic movement of the Holy Spirit, and a judgement on traditional religious institutions which have absolutely failed to inspire the rising generation.

However, McEntee and Bucko also claim to be monks, New Monks. And this is where I am having a bit of trouble. Traditionally, a monk (from Monachos for alone, single) was a celibate, vowed religious seeker that either lived in solitude or in community. In Judeo-Christianity, this tradition goes back as far as the Essenes in Palestine, but really got kicking in the third century with a growing number of hermits that fled the cities to do battle with demons and live like Jesus of Nazareth. In the fifth century, Saint Benedict of Nursia famously wrote a rule to organize the disparate lives of these seekers which has been a model for monks and hermits ever since. Monastic communities have been valuable stores of contemplative wisdom for centuries, but they have also had a tendency (not universal) to approach the world dualistically. The monk sought to abandon the world and transcend the body for a life lived for God and the spirit.

For the authors, a New Monasticism “names an impulse that is trying to incarnate itself in the new generation” (15), an impulse that is not only Inter-spiritual, as in embracing several religious traditions at once as proposed by lay monastic Wayne Teasdale, but also nondual. By nondual the authors mean that it seeks to engage the world rather than transcend it, and to live out their spiritual vocations in that world. Nondual spirituality seeks unitive consciousness that does not distinguish between heaven and earth, body and soul, or even God and human. Nondual spirituality seeks union with God through the world rather than in spite of it. The simplest qualification then for a New Monastic is “to denote a level of commitment to one’s spiritual life” (xv). For the authors this commitment transcends the traditional vows of stability, celibacy and strict adherence to a single tradition. The New Monk seeks to transform the world as much as she seeks to transform herself. Engaged in the world, there can be no split between the outer and inner life. Whereas the early monastics desired to transform the world into Paradise through their Benedictine work ethic, a world free from danger, disease, hunger, and toil; New Monastics seek to transform the world to be free of poverty, injustice, violence and ecological destruction.

However, the authors are clear that any attempt at an authentic New Monasticism outside the walls of a monastery cannot simply be another Facebook Group with misty memes of monks walking down long corridors and vague quotes about stillness or silence. Nor can it be a Secular or Third Order monthly retirement club. Like traditional monasticism, the New Monks must be dedicated to a rigorous spiritual practice and the authors articulate nine Vows that correspond to this spiritual path. But unlike the vows of chastity, poverty, obedience and stability, the New Monastics weave together ecology, morality, nonviolence, social justice, service and self-knowledge:

- I vow to actualize and live according to my full moral and ethical capacity.

- I vow to live in solidarity with the cosmos and all living beings.

- I vow to live in deep nonviolence.

- I vow to live in humility and to remember the many teachers and guides who assisted me on my spiritual path.

- I vow to embrace a daily spiritual practice.

- I vow to cultivate mature self-knowledge.

- I vow to live a life of simplicity.

- I vow to live a life of selfless service and compassionate action (xxxv).

I vow to be a prophetic voice as I work for justice, compassion and world transformation.

This is an impressive list of vows, much longer than even the strictest monastic community. Yet, some have expressed concern that framing the emerging spirituality as New Monasticism denigrates or seeks to replace the ‘Old’ monasticism. The authors are clear that they do not see themselves replacing the traditional monastic vocation. Rather, New Monasticism needs traditional monasticism, and compliments it. I also understand framing an emerging spiritual sensibility as “New”, because it doesn’t fit traditional monastic practice, but isn’t wholly other either. Like new species emerging from a common ancestor, the ancestor doesn’t necessarily become obsolete.

For me however, it is not the word ‘New’ that I have the trouble with; while the emerging spirituality may be ‘New’ I am not sure it is necessarily monastic. There seems to be a difference between updating monastic practice and institutions to cope with the modern world, and saying that the contemplative inter-spirituality emerging from the so-called Second Axial Age is monastic. While I would certainly say that all monks are contemplatives, not all contemplatives are monks. Therefore I was not entirely convinced that the New Monasticism is not simply a New Contemplation with a particular dedication to social justice and Interfaith dialogue.

As far as Christian spirituality is concerned, the balance the authors seek between contemplation and action is not new, but it is not associated with monasticism; rather it is more akin to their 12th century descendants the Friars (Franciscans and Dominicans) who lived in cities, served the poor and sought to balance an active life with a life of prayer. The Friars were for all intents and purposes ‘New’ to the scene of Catholic spirituality, adapting their spiritual practices and vows to live fully immersed in the world, however, they left the label monk behind.

The authors might then argue that a monk is simply someone who seeks God, and they spend a great deal of time in the book defending a kind of archetypal monk that each of us carries, some more than others. This monk-as-archetype rather than as vocation seems to lose sight of the fact that monasticism is a social institution. Monks carry out their vocations on behalf of the Church. They make up one part of the body of Christ, whose sole purpose is to pray. Monks are an integral part of that body, they pray and praise God on behalf of the church which is all connected. In this sense, a monk outside of a monastery is like a fish out of water, a tiger in a zoo; it doesn’t make sense ecologically.

Lastly, monks are known for their vow of stability, which has led many to call monks ‘lovers of the place.’ This commitment to a single community, a single piece of land has very much shaped the monastic vocation since at least the time of Saint Benedict. While I commend the author’s vows, and their globalized, archetypal approach, without a sense of place, I am having a hard time reading it as monastic (which is obviously biased by my PhD work with land-based monks).

But I could certainly be convinced. I feel a strong sense of vocation toward the Contemplative life, and have certainly thought about becoming a traditional monk (at least on my most prayerful days). But most of the time, like the authors, I feel my talents and passions are better severed engaged fully with the world (as much as it frustrates me).

I write all this because I would like to continue the conversation. I would like to humbly call for a global gathering of Monastics ‘New’ and ‘Old’ for some time in 2017 to discuss ways to promote traditional monastic vocations, clarify emerging movements inspired by monasticism and learn from communities that are on the frontier of such movements. While Jesus may have said that we should not put new wine into old wine skins, there is nothing wrong with putting old wine into new bottles!