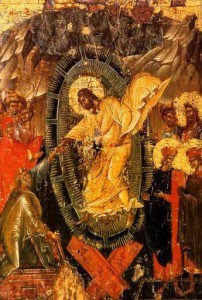

The harrowing of hell

A harrow is a spiked implement that is drawn over ploughed land to break up clods, tear up weeds, and level the ground for planting. Knowing that bit of agricultural history gives the common figurative use of the word harrowing an important layer of meaning. We speak of a harrowing experience—one that is hair-raising, unnerving, that disturbs our peace and challenges our sense of security.

Whatever in us remains to be broken up and rooted out so that we may be made fertile and fruitful may need to be harrowed.

The early church doctrine of “the harrowing of hell,” –that after his death Christ burst the very gates of hell to redeem the dead—is not in the Gospel record, but makes complete sense, given what he came to earth to do. A God who is not bound by time would not be bound by the pastness of the past. And if the message of the Gospel is that death has been conquered, a gathering of the dead into the great Now of the Kingdom of Heaven would seem a fitting completion of that promise and fact.

The liturgy of Holy Saturday focuses not only on the empty altar and the appalling fact of what happened when humankind rejected Love, but also on the depth, as well as the breadth of that love. Christ stretched out his arms on the cross in an embrace that encircled the world; he also descended to hell itself to lift all of humankind into that Now.

I have long loved Psalm 139 for its exuberant confidence, but especially for this reassurance:

Where can I go from your spirit?

Or where can I flee from your presence?

If I ascend to heaven, you are there;

if I make my bed in Sheol, you are there.

If I take the wings of the morning

and settle at the farthest limits of the sea,

even there your hand shall lead me

and your right hand shall hold me fast.

In older translations the Hebrew term for the place of the dead, Sheol, is translated as hell. I like that translation; it seems appropriately jarring. Besides which, the idea that I might “make my bed” in hell is a strong reminder that I am capable of doing just that—convincing myself that I can be happy and at home in the squalor of gluttony, lust, sloth, avarice and the whole list of other habits that keep one self-focused and afraid. But it’s also a place, thank God, that is pathetically ramshackle and offers no protection from the “Hound of Heaven”—poet Francis Thompson’s image for the Spirit who hunts us down to bring us home. The long, glorious poem of that title begins with words in which I imagine many of us might recognize an element of our own stories:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.

The poem continues, a narrative of flight and pursuit by “those strong Feet that followed, followed after.” It ends with a triumphant invitation to the captive, “Rise, clasp my hand and come!” and an accusation so kind it serves as a word of welcome:

‘Ah, fondest, blindest, weakest,

I am He whom thou seekest!’

Nowhere are we beyond that outstretched hand. Most parents know that, though there might be offenses that would divide them from a beloved child by distance or disagreement or distrust, nearly nothing could quite obliterate their love. And so we have the more reason to imagine that the Holy One who is Love itself will stop at nothing—not even the gates of hell—to find us and make us whole and bring us home. This is why Holy Saturday deserves its own celebration. This is very good news.