Other than tradition that Jonah is historical, there is the New Testament argument. This argument is fairly common and made by non-LDS as well as LDS, but on examination, I think it’s insufficient to prove what its proponents claim. This also applies, by the way, to Lot’s wife turning into a pillar of salt (Luke 17:32), and Job (D&C 121:10).

Other than tradition that Jonah is historical, there is the New Testament argument. This argument is fairly common and made by non-LDS as well as LDS, but on examination, I think it’s insufficient to prove what its proponents claim. This also applies, by the way, to Lot’s wife turning into a pillar of salt (Luke 17:32), and Job (D&C 121:10).

What’s really at stake here? Not much, I think, but perhaps an opportunity to break down a wall. Most often, I’ve seen the New Testament argument used in such a way to accuse those in the non-historical camp of lack of faith, either in God’s power, Jesus, or the scriptures. I fully believe in all three of those , but I’m also of the opinion that Jonah was meant as a didactic Israelite parable. I also affirm that Jonah is true (see my Jonah podcast) I’ll take the Institute manual (and secondarily then-Elder Joseph Fielding Smith) as my example. “That Jonah’s story is a true one, and not an allegory as some scholars maintain, is evidenced by 2 Kings 14:25 and three New Testament references.”

First, I take issue with the falsely dichotomous usage of “true… and not an allegory.” Apparently by “true” the manual means “both historical in nature and accurate.” I’ve seen this uncritical equation of “true” with “historical” among LDS more than I’d like. But truth need not be historical. What if we substituted one of Jesus’ parables into that sentence in the manual? How many LDS would be comfortable with the sentence “That the Samaritan’s story is true, and not a parable as some maintain…” Are parables, allegories, and similar things “false” by their very nature? I don’t think so. It appears fairly self-evident that parables can be both true and non-historical in nature, but this line of thinking isn’t evident in the Institute manual. Certainly it means we need to think clearly about what we mean by “true.”

Second, the manual cites Joseph Fielding Smith, who said, “My chief reason for so believing [that Jonah is historical] is not in the fact that it is recorded in the Bible, or that the incident has been duplicated in our day, but in the fact that Jesus Christ, our Lord, believed it. The Jews sought him for a sign of his divinity. He gave them one, but not what they expected. The scoffers of his day, notwithstanding his mighty works, were incapable, because of sin, of believing.” ( Doctrines of Salvation, 2:314–15.)” Smith then quotes Matthew 12:39-40 as prima facie evidence that Jesus believed Jonah was historical.

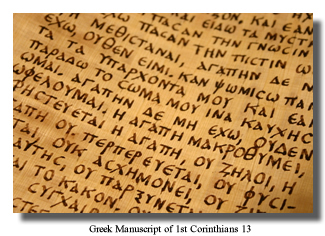

I’m no lawyer, but I see too many assumptions that must all be true for this to actually prove what it is claimed to prove. Let’s assume for sake of argument that Jesus actually said this. (This brackets the major issues of textual criticism, translation/transmission from Aramaic>Greek>English, as well as the fact that the Gospels were written decades after Jesus’ death and may well represent more of traditions/views about Jesus than verbatim documentary accounts.)

We must then make two assumptions.

1) Jesus’ knowledge of Jonah was divine or revealed, and not just based on received Jewish tradition.

2) Jesus would not make a comparison to a non-real or allegorical person or event, because such comparisons are inherently invalid.

We can’t say anything for certain about #1, but it’s clear that there were some things Jesus did not know (Matt 24:36/Mark 13:32). It also seems logical that Jesus learned through human means as well as by revelation as he grew “from grace to grace.” It’s also clear that Jesus tended to work within then-current worldview of first-century Jews, and even use it against them from time to time. (Similar things happen today. I can even think of examples where two parties have different views of the reality of something, and one uses it against another. For a stupid example, take small children and the boogeyman. Adults know there’s no such thing, but children may believe it, and we sometimes use their own belief in it against them for play or to get them to go to bed. I see no reason why Jesus could not have done so with the Jews.)

Tradition has left no record that Jesus taught anything about basic life-saving personal hygiene or that he tried to get rid of slavery; he didn’t try to undermine the worldview but used it to teach his gospel. To what extent or at what point his own worldview and knowledge transcended that of his mortal companions and cultural into which he was born we can’t really say.

But, again, let’s grant assumption #1.

Assumption #2 is the real kicker, that Jesus would not make any comparison or analogy to Jonah unless Jonah were actually real and had been in a fish for 3 days. But this, on examination, is simply false. This is done all the time. People compare real-world events to those they’ve seen in movies or read in books that they know to be fictional.

I’ve seen comparisons of boyfriends or crushes to Edward the Vampire (who may be Mormon). I’ve seen The Onion compare the events of September 11th to a Jerry Bruckheimer film, as well as many comparing those events with Tom Clancy’s book in which a Japanese airliner is flown into Congress as a terrorist act. Those are the examples I was able to come up with in a short sitting. I’m sure there are many more. We make comparisons of actions, events, appearances and other things, to those we know from fictional accounts, but those comparisons, in and of themselves, have no bearing on the nature of the object of comparison. Jesus can refer to Jonah and the fish and Jonah can still be allegorical.

In short, the New Testament argument, that Jesus believed Jonah was historical, is founded on multiple assumptions that are easily contradicted and undermined, and are insufficient to establish that Jonah was historical. Ultimately, as the First Presidency thought, the historicity of Jonah is irrelevant; what matters is the doctrine and principles taught in Jonah, which have nothing to do with the fish. (See my podcast.)