I was recently told by an acquaintance that Thanksgiving was a “bogus” holiday. I’m still not sure what was meant by that, but I was bothered none the less. Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. There’s no pressure, no real work (and I say that as someone who cooks a fifteen course meal that day), no rituals to write, and no presents to buy. It’s the calm before the storm of Yuletide and a chance to reflect and surround ourselves with many of the people that we love and care about. It’s a holiday devoted to eating and watching football, what’s not to love? I get to watch the NFL and put gravy on everything? I’m all in.

I was recently told by an acquaintance that Thanksgiving was a “bogus” holiday. I’m still not sure what was meant by that, but I was bothered none the less. Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. There’s no pressure, no real work (and I say that as someone who cooks a fifteen course meal that day), no rituals to write, and no presents to buy. It’s the calm before the storm of Yuletide and a chance to reflect and surround ourselves with many of the people that we love and care about. It’s a holiday devoted to eating and watching football, what’s not to love? I get to watch the NFL and put gravy on everything? I’m all in.

In many ways Thanksgiving is the most organic of America’s holidays. Christmas, Halloween, and even Easter owe a lot of their popularity to marketing and Madison Avenue. I’m not saying those aren’t enjoyable holidays, but they have been far more “manufactured” than Thanksgiving. While many holidays feel timeless, the ways in which we celebrate them tend to be much more modern than people think. Thanksgiving is possibly the oldest (widely) continually celebrated holiday in the United States. Thanksgiving has always been a holiday celebrated without an agenda other than eating. Today it’s the gateway to another far more commercial holiday, but a Thanksgiving dinner in 2012 still looks a lot like a Thanksgiving dinner in 1822 (though they ate a lot more pies back then).

The origins of Thanksgiving lie in two places: the English countryside and New England. Thanksgiving is a direct descendant of English Harvest Home celebrations, possibly containing echoes of Britain’s pagan past. I’ve always liked to joke that if the Pilgrims had been better farmers we’d be celebrating Thanksgiving in September, but that’s not quite true. Harvest celebrations in November make a lot of sense when you remember that there are less chores to do that time of year. After a busy few months of farming, November was a quieter time. I doubt that farmers are ever completely idle, but there is less activity at the start of winter.

The origins of Thanksgiving lie in two places: the English countryside and New England. Thanksgiving is a direct descendant of English Harvest Home celebrations, possibly containing echoes of Britain’s pagan past. I’ve always liked to joke that if the Pilgrims had been better farmers we’d be celebrating Thanksgiving in September, but that’s not quite true. Harvest celebrations in November make a lot of sense when you remember that there are less chores to do that time of year. After a busy few months of farming, November was a quieter time. I doubt that farmers are ever completely idle, but there is less activity at the start of winter.

Thanksgiving is also a New England Yankee holiday, and because of those roots, a Puritan holiday. At its beginning in the mid 17th Century it emphasized family and church going as much as eating. Thanksgiving up until the middle of the 19th Century was often celebrated with long sermons both in the morning and the late afternoon. Eating was a welcome respite between hours of preaching, at least when it was actually allowed. Many early “Thanksgiving” celebrations were very un-celebratory; some communities actually fasted instead of eating turkey.

The odd custom of celebrating the Thanksgiving holiday on thursday also began with the Puritans. As strict observers of the sabbath, the holiday would have been impossible to celebrate on the weekend, or even earlier in the week. Consideration had to be given for how long it might take to put together a feast (no easy task in those days), and how long it might take to clean up that feast and prepare for the sabbath. In the middle of the week, thursday worked exceptionally well. Keeping the holiday far from sunday also allowed the Puritans to visit neighbors on Thanksgiving or travel in order to see family.

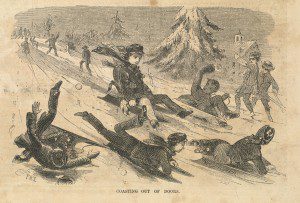

When people today talk about “The War on Christmas” it’s obvious that they are unfamiliar with the greater history of that holiday. The Puritans, first in England and then later the United States, were some of the first to wage war against Christmas; in fact they didn’t celebrate it for literally centuries. In many ways Thanksgiving came to represent a “Puritan Christmas” and by the early 19th Century it often looked a lot like its December cousin. We take fall imagery for granted at Thanksgiving, but many New Englanders used more wintry landscapes when depicting the holiday, and a lot of early Thanksgiving celebrants went sledding or ice-skating on Turkey Day.

When people today talk about “The War on Christmas” it’s obvious that they are unfamiliar with the greater history of that holiday. The Puritans, first in England and then later the United States, were some of the first to wage war against Christmas; in fact they didn’t celebrate it for literally centuries. In many ways Thanksgiving came to represent a “Puritan Christmas” and by the early 19th Century it often looked a lot like its December cousin. We take fall imagery for granted at Thanksgiving, but many New Englanders used more wintry landscapes when depicting the holiday, and a lot of early Thanksgiving celebrants went sledding or ice-skating on Turkey Day.

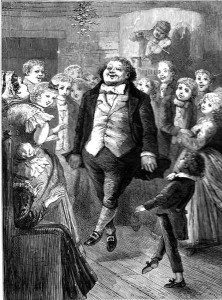

Most Americans don’t sing the tune “I’ll Be Home for Thanksgiving” (though it is a hugely busy travel week), but to New Englanders in the 19th Century that was the time to go home. It became a social holiday, a time to reunite with family, especially as the United States become more urban and less agrarian. As the religious elements of the holiday began to wane around that time it evolved into an occasion for large social gatherings, with a large amount of dancing and celebration. Thanksgiving night in a New England town circa 1830 probably looked like a Christmas gathering at Old Fezziwig’s (and if you don’t know Fezziwig, read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol).

Most Americans don’t sing the tune “I’ll Be Home for Thanksgiving” (though it is a hugely busy travel week), but to New Englanders in the 19th Century that was the time to go home. It became a social holiday, a time to reunite with family, especially as the United States become more urban and less agrarian. As the religious elements of the holiday began to wane around that time it evolved into an occasion for large social gatherings, with a large amount of dancing and celebration. Thanksgiving night in a New England town circa 1830 probably looked like a Christmas gathering at Old Fezziwig’s (and if you don’t know Fezziwig, read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol).

Thanksgiving celebrations were widely popular in New England, and as those Yankees travelled across the young United States they took their Puritan Fall Holiday with them. Strangely, Thanksgiving would not become a national holiday until 1863, until then it was a holiday celebrated state by state. Governors would issue proclamations calling for a “Day of Thanksgiving” to be celebrated sometime in late November (though it could be celebrated as early as October and as late as January). George Washington once proclaimed a national day of Thanksgiving in 1795, addressing “All religious Societies and Denominations(1)” and resisting the opportunity to make Thanksgiving a national Christian holiday. Other early Presidents also proclaimed various “Thanksgivings” at odd times of the year, but those proclamations bear only a slight resemblance to our Modern Holiday. When Thanksgiving was proclaimed in March or August, New Englanders (and those that traced their roots there) went ahead with celebrating the holiday on the last thursday of November.

It was Lincoln who proclaimed the first recognizable, national Thanksgiving day, and he might not have done so had it not been for the insistence of Sarah Josepha Hale. Hale might accurately be described as the “mother” of Thanksgiving. A New Englander, she argued passionately in the pages of the magazine she edited, Godey’s Ladies Book, for Thanksgiving as a national holiday. Godey’s was one of the most widely circulated periodicals of its day, and thanks to Hale’s love of the holiday, it began to be celebrated across the country. Hale was a tireless champion on behalf of the holiday and wrote to several U.S. Presidents imploring them to make the day a National Holiday. She was able to finally convince Lincoln, and the holiday began to be celebrated by Presidential Proclamation across the country. (As a “Yankee” holiday Southerners were slow to embrace the holiday before the Civil War, and then hesitant to pick it back up afterwards. As a former Southerner that’s almost impossible to fathom now.)

It was Lincoln who proclaimed the first recognizable, national Thanksgiving day, and he might not have done so had it not been for the insistence of Sarah Josepha Hale. Hale might accurately be described as the “mother” of Thanksgiving. A New Englander, she argued passionately in the pages of the magazine she edited, Godey’s Ladies Book, for Thanksgiving as a national holiday. Godey’s was one of the most widely circulated periodicals of its day, and thanks to Hale’s love of the holiday, it began to be celebrated across the country. Hale was a tireless champion on behalf of the holiday and wrote to several U.S. Presidents imploring them to make the day a National Holiday. She was able to finally convince Lincoln, and the holiday began to be celebrated by Presidential Proclamation across the country. (As a “Yankee” holiday Southerners were slow to embrace the holiday before the Civil War, and then hesitant to pick it back up afterwards. As a former Southerner that’s almost impossible to fathom now.)

While Thanksgiving would not be a fixed national holiday until 1941, it was celebrated by Presidential Procolmation annually from 1863 to 1938 always on the last day of November. In 1939 a well intentioned Franklin Delano Roosevelt moved the holiday up one week, from November 30 to November 23 (to increase the Christmas shopping season). Because Thanksgiving had become a “fixed” holiday in the minds of so many Americans, FDR’s decision was met with a great deal of criticism. If you think we are divided today, things were even worse in 1939. Nearly half the union celebrated Thanksgiving on November 23 (dubbed that year “The Democrat Thanksgiving”) while the remaining 24 states celebrated “The Republican Thanksgiving” on November 30. Some states celebrated both dates as official holidays, and college football schedules were damaged by FDR’s date switch. Due to the controversy Thanksgiving became an official holiday in 1941, with its date of celebration set to the “fourth thursday in November” as a compromise. (It’s a good one too making November 22 the earliest Thanksgiving can be celebrated.)

While Thanksgiving would not be a fixed national holiday until 1941, it was celebrated by Presidential Procolmation annually from 1863 to 1938 always on the last day of November. In 1939 a well intentioned Franklin Delano Roosevelt moved the holiday up one week, from November 30 to November 23 (to increase the Christmas shopping season). Because Thanksgiving had become a “fixed” holiday in the minds of so many Americans, FDR’s decision was met with a great deal of criticism. If you think we are divided today, things were even worse in 1939. Nearly half the union celebrated Thanksgiving on November 23 (dubbed that year “The Democrat Thanksgiving”) while the remaining 24 states celebrated “The Republican Thanksgiving” on November 30. Some states celebrated both dates as official holidays, and college football schedules were damaged by FDR’s date switch. Due to the controversy Thanksgiving became an official holiday in 1941, with its date of celebration set to the “fourth thursday in November” as a compromise. (It’s a good one too making November 22 the earliest Thanksgiving can be celebrated.)

By the late 19th Century Thanksgiving was home to several traditions we now associate with Halloween. In New York City Thanksgiving was often celebrated by dressing up in elaborate costumes, looking more like a Halloween or Mardi Gras parade than the modern holiday. There were also activities that looked a lot like trick or treating (or wassailing) as well. It wasn’t until after World War II that many of our “timeless” holiday traditions were shuffled into their current positions. By the middle of the 20th Century Thanksgiving had truly become a quieter holiday about food, family, football (first the college game and later the NFL), and thanks, but it did take several centuries to get there. Thanksgiving was first celebrated in the 1600’s, became recognizable by the early 19th Century, and then settled into its current position only in the last seventy years or so.

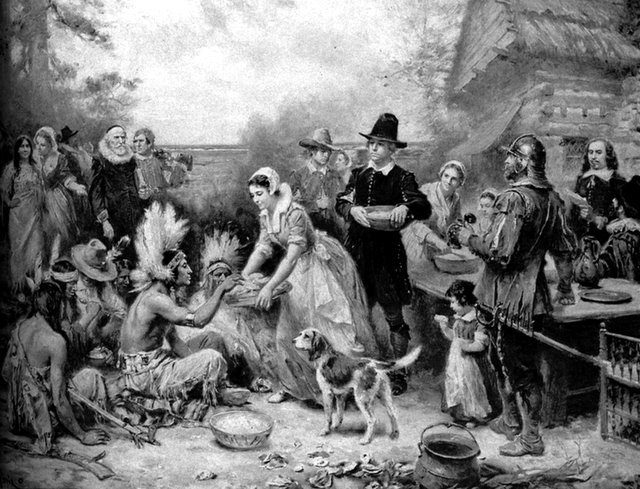

All of these words and nothing about the Pilgrims, but there was a time when Thanksgiving didn’t focus on the Pilgrims of Plymouth. They were reintroduced into the holiday at the end of the 19th Century as an object lesson. Stories of the “first Thanksgiving*” began popping up in school books to illustrate an idealized version of America and its history. The Pilgrim story illustrated the value of the Protestant work ethic and painted a picture of a tolerant America. It was both a heart-warming story, and an opportunity to “Americanize” a largely Catholic immigrant population.

It’s true that the Pilgrims did celebrate some sort of Thanksgiving back in 1621**, and it did come with Native Americans, pumpkin, and probably wild turkey. Unfortunately it wasn’t necessarily a holiday about “coming together” so much as it was about showing off English muskets. In recent years much of the Pilgrim myth has been stripped away. Most Americans are now aware that the Puritans of Plymouth Rock weren’t really the nicest folks. I’m respectful of their dedication to hard work and devotion to their faith, but they weren’t necessarily pioneers of religious freedom. Sure they were interested in their religious freedom, but not really that of anyone else. The myth has always been better than the reality, but I still find value in it. When people reflect on the Pilgrims and the Patuxet it’s a reflection not of what actually was, but what we wish to be. Most of us do dream of a country where everyone can come together to share a meal without caring about race, creed, or gender.

Maybe that’s why Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. It speaks to the best of what we can be. It’s certainly about food and family, but it’s also about coming together despite our differences. I’ll eat a good pound of turkey next Thursday, hug my wife, call my Dad, and watch about ten hours of football, but I’ll also stop to remember what it means to be truly thankful for the blessings in my life, and to reflect on the things that bring us together instead of drive us apart.

Happy Thanksgiving.

*Other Possible First Thanksgivings: Texas 1541, Florida 1564, Maine 1607, and probably most famously Jamestown Virginia 1610. Culturally the modern Thanksgiving has more to do with the early celebrations in New England, but probably not the most famous one back in 1621.

**Later celebrations of “Thanksgiving” in Plymouth Massachusetts were far more bloody and shameful. A 1637 version of the holiday was especially awful.

1. Thanksgiving: An American Holiday, An American History by Diana Karter Appelbaum, page 57.