Various pundits, including no less a figure than Leo Tolstoy and Harold Bloom, have dubbed Mormonism a distinct—or, even further, the quintessential—American religion. Yet the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has long maintained a tenuous relationship with the United States, much of which has been and will continue to be featured during Mitt Romney’s presidential run. While some have emphasized the “American-ness” of Romney’s religion, others have mused on the perceived chasm between the two. Most recently, journalist Sally Denton claimed, “Mormonism’s founding theology was based upon a literal takeover of the U.S. government.” While such opining seems disappointingly repetitious in a day where Krakauer’s aphotic Under the Banner of Heaven is used as a test case to better understand radical Islam (becoming the best-selling book on the LDS faith to date), it neglects and oversimplifies a complex history that offers much to learn about not only Mormonism but also the culture in which it developed.

To present Mormonism as an aberration to the American tradition only serves to perpetuate the myth of the nation’s harmonious religious past. In a potent and important way, the LDS church’s dynamic relationship with the United States is only indicative of the American experience writ large. Indeed, to continually parade LDS historic contestation with American culture as an extreme abnormality does a disservice to the complexity and richness of American religious history.

As much as the nation wishes to buy into the ideal separation between church and state, there have been constant bumps and bruises not too dissimilar from Mormonism’s tale. All religious movements have sought to exert national influence—and wished to have exerted more—while also being rebuffed and disillusioned. From New England Congregationalists seeking to dictate original state constitutions to Southern Baptists arguing for racial segregation, and from Evangelicals fighting for school prayers to liberal Protestant groups petitioning for same-sex marriage, all religions in the United States have at one time or another challenged the blurry distinction between church and state.

From the start, the culture in which Mormonism was born and bred was simultaneously a triumphant and unsteady time for Protestantism. A vibrant religious marketplace led to the flowering of many upstart religious movements with variant expressions of faith claiming national legitimacy, yet the relationship between religious belief and American citizenship remained astoundingly tenuous. Many claimed to be a distinctly “American” religion, yet what “American” meant was contested and ambiguous. As a result, religions not only assimilated to national themes but paved new directions and established new patterns. This was not a smooth process, as lines were constantly drawn and redrawn, and frequent clashes between various religious groups and the American government made national progress more an awkward mishmash of results than a neat and tidy linear development. The paradoxes at the heart of America’s current national identities—a proclaimed secular government free from institutional religious influence, yet with unquestioned if uncomfortable ties to a vibrant religious base—epitomize this amorphous growth, of which the LDS religion played a small, if important, part.

Most of those who founded and converted to Mormonism in its first decades were descendants of the revolutionary generation raised in a period of patriotic hubris. This devotion, however, was severely tested as Mormons were forced out of their communities as a result of controversial voting, racial, and marital practices, and were unable to secure restitution from local—and later, federal—governments. But even through deep conflicts with competing religionists and citizens, they still held on to what they believed to be the pure patriotism of America in the face of being denigrated as outcasts; even if America didn’t want them, they still yearned to be Americans.

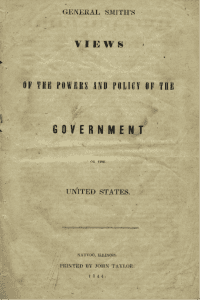

For instance, shortly after Mormons were kicked out of their settlement in Independence, Missouri—the first of many conflicts between Mormons and their neighbors—Joseph Smith dictated a revelation stating that God himself “established the constitution of this Land by the hands of wise men whom [he] raised up unto this very purpose.” A decade later, while settled in a quasi city-state of Nauvoo, Illinois, Joseph Smith’s solution to state and federal difficulties was not to retreat from the nation, but to run for the American presidency himself; if others weren’t willing to follow American’s ideals, Smith thought, he might as well do it himself—not an impulse too distant from the rhetoric of today’s presidential candidates who identify divine prodding at the root of their political aspirations.

Even after Smith’s murder, an event Mormons believed to be the darkest moment in the nation’s history, the church still didn’t sever ties with the United States; if anything, they saw themselves as the last harbingers of America’s founding principles. Channelling Thomas Jefferson, one LDS apostle penned a satiric editorial titled “American Independence Declared Over Again,” in which Mormon pioneers now stepped into the place of the revolutionaries of 1776 in claiming their “inalienable rights” of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This patriotic mimesis may seem comical today, but it hints to the deep and complex psyche of a group of people as possessive of their title of “American” as their title of “Saint.”

As a final example, Mormons were recruited in 1847 by the government to help in the then-raging Mexican War. As this was in the middle of the Church’s supposed “exodus” from the country, it would have been easy for them to refuse to help a nation that had just forced them from their borders. Yet in a decision mixed with pragmatism and patriotism, Mormons accepted the request and organized their volunteer troop. Fittingly, and representative of the ambivalent relationship between the Mormons and the government they were now helping, the military unit chose to march with an original American flag containing thirteen stars, aptly symbolizing Mormonism’s sustained commitment to the nation’s ideals even if it wasn’t fully supportive of the current incarnation. When this rhetorical display—in which a return to founding ideals is the necessary antidote to a contemporary and corrupt government—is compared to the broader scope of religious history, Mormonism’s actions appear as American as apple pie.

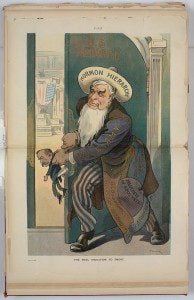

Tensions between religious conviction and patriotic commitment, of course, continued to plague Mormonism for many decades. But those tensions never reached a tipping point: when America gained possession of the Mormon territory, Latter-day Saints quickly petitioned for statehood and attempted to fill all local government positions; when an 1857 “Utah War” nearly erupted, resolution was achieved prior to any formal battles; and when anti-polygamy legislation reached an apex, the LDS church relented and denounced their controversial marital practice. The more Mormonism was confronted with the demands of a democratic and secular nation, the more they eventually acquiesced by privatizing their theocratic and undemocratic beliefs. Eventually, they achieved statehood, embraced America’s two-party system, and did their best to fit within the confines of America’s political body. By the time Mitt Romney announced his run for president, his family was representative of most American Mormons in that they claimed entrenched ties to the American political system that spanned several generations.

This is the American story, because Mormonism, at every step, echoed tensions found throughout United States history. Continual strains of contention and assimilation dot the historical record of nearly every major religious tradition, as all attempted to navigate the tenuous waters of church and state. Religious freedom and democratic government are a potent and combustible blend, with results spanning a long and dynamic spectrum. Any examination of the historical relationship between Mormonism and the American nation, then, is akin to looking in the proverbial mirror of American culture. So instead of providing an amusing—or, even worse, threatening—image of Mormonism’s history, Mitt Romney’s singular religion provides only a reflection of a national narrative we often would rather forget.

In the end, Mormonism’s “unique” relationship with America is all the more, well, American.