I’ve been, as Mormons say, “less active” here at the blog for the past few months. A number of changes have forced me to contribute less—among them graduation (“Doctor Spencer,” now!) and a move to Utah. And I’ll now actually be signing off from the blog entirely. I’d like to make one last contribution before doing so, and that in form of a review. A few days ago, I had the opportunity to attend the press conference held in connection with the release of the newest volumes of the Joseph Smith Papers Project, and that event turned out to be crucial for a set of reasons. Here I’ll offer a review of the new volume—or really, volumes; it comes as a pair—as well as some reflections on the event.

I’ll assume general familiarity by now with the Joseph Smith Papers Project. This newest publication marks a major milestone, in my view. Where what’s been made previously has had its focus chiefly on things of historical value—Joseph’s journals and histories, revelations and letters—this newest release focuses on the Book of Mormon. Published in two “parts” that together make up Volume 3 of the Revelations and Translations series, the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon has been made fully available. The editors have here followed the format of the first volume of the same series, which published beautiful photographs of the early manuscript revelation books; here we have full photographs of the whole of the printer’s manuscript, along with full transcriptions.

The format of the publication, which follows the JSP standards already established, makes this immensely easy to read. For those who have used Royal Skousen’s transcripts of the printer’s manuscript, available in print for more than a decade already, the ease of use of these new volumes will be immediately clear. Skousen’s transcripts have to be turned sideways to be read, making use somewhat awkward, and Skousen used his own idiosyncratic symbols to mark features of the text. In the JSP version, what have now become standard symbols are used, and colors rather simply identify scribes so that it’s unnecessary to relegate such information to footnotes. Add to this the fact that full photographs of the actual manuscript are included, and you’ll see why this publication marks a real advance in making the printer’s manuscript available.

Of course, Skousen is one of the editors of the volume, so none of this should be understood to be a criticism of his work! The editors note that they’ve taken over from Skousen’s earlier work all of his insights into the content of the manuscript, and they also note that the format of the JSP volumes means that some of Skousen’s findings don’t appear in the JSP publication, since Skousen’s transcript looks in more detail than the JSP sees fit to do. For those hoping to work on the critical text of the Book of Mormon, then, Skousen’s transcript will still be a useful and even necessary volume. The level of detail found there exceeds what’s found here. Nonetheless, the JSP publication of the printer’s manuscript will likely become the standard source for future scholarly discussion.

There are other reasons to be glad about the accessibility of this presentation of the printer’s manuscript. Critics of the Book of Mormon have occasionally used small slices of the printer’s manuscript to make it seem as if the translation was more of a composition than an oral dictation, as if Joseph Smith were carefully reworking the text for publication. This publication makes every major detail associated with the printer’s manuscript fully available, and there’s enough information here to make clear that edits made to the manuscript were focused on grammar and undertaken in connection with the 1837, second edition of the Book of Mormon. The translation effort itself, it’s all the clearer for those unfamiliar with the details, was a virtuosic (if not exactly grammatically fluent!) oral performance.

Most useful, of course, is simply the availability of these documents. And it’s to be noted that the photographs and transcripts will soon be available online for free at the JSP website. Those interested in Book of Mormon manuscripts will be happy to know that there are also plans to produce a further volume with the original manuscript (what’s left of it).

All this is reason to celebrate. And then there’s more. The press conference announcing the release of the volumes turned out to be unprecedented in two ways.

First, it was the first press conference ever undertaken together by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Community of Christ. The event marks a watershed in the relationship between these two Restoration churches. Elder Snow, Church Historian and member of the Seventy in the LDS Church, spoke alongside President Linkhart, president of the Seventy in Community of Christ. To see the two sharing a pulpit in the Church History Library was a remarkable experience, and both made themselves available for interview with representatives of the press after their talks. What brought these two churches together for this event, of course, is the fact that the printer’s manuscript is in the possession of Community of Christ, kept in their archives in Missouri. The two churches have been working together on making the printer’s manuscript available for twenty years, so that this press conference marks the culmination of a long relationship of good will. I sincerely hope we see relations between the two churches continue on such friendly terms.

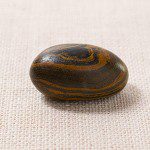

Second, as has been widely discussed the past few days, it was decided to include in the newly published volumes the first-ever published photographs of the seer stone most likely used by Joseph Smith in translating the Book of Mormon. The volume includes four glossy photographs and a full account of the provenance of the stone. The photographs appear, moreover, in the course of a detailed introduction that spells out much of the history—history well known to those acquainted with Mormon history, but less known to average members of the Church. This marks a major development of the LDS Church’s public discussion of seer stones over the past year or so. Beginning with the topics essays at lds.org, the Church has been forthcoming about the fact that Joseph translated by using a seer stone, which he placed in a hat (to exclude the light) while he dictated the Book of Mormon’s text to his scribe. Released the same day as the new volume, an article slotted to appear in print in the October Ensign magazine will discuss the seer stone and the process of translation for as popular an audience as can be imagined. This marks a major shift in historical transparency.

I’ll vocalize my concern that this last development especially is already tending to overshadow the publication of the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon. I’m thrilled to see the seer stone made public, if only so that it can cease to be such a mystery, and so that Latter-day Saints can incorporate it into their understanding of early Church history. But I’m far, far more thrilled by the manner in which the earliest sources for the text of the Book of Mormon are being made public. The consequences of this publication for the future of Book of Mormon studies will be enormous.