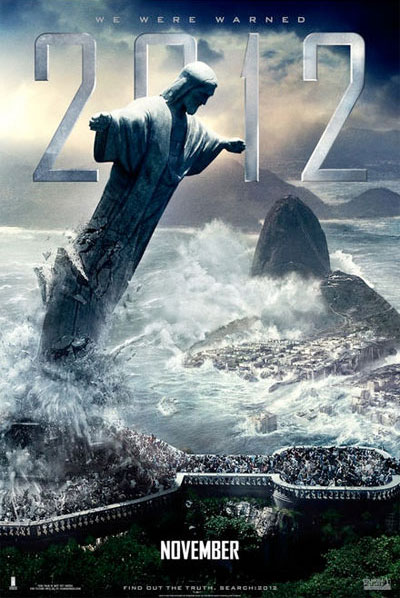

I just finished watching the movie 2012, which uses religious imagery and ideas in interesting ways. On the one hand, there is a strong anti-religious message. It is as though every time someone prays in the movie, their death is ensured to follow shortly thereafter. Now it may be fair to poke fun at those who would choose prayer rather than science when facing a disaster of which science is the prophet predicting it. But 2012 seems to go further, for instance when it highlights that the Italian prime minister does not survive, because he chooses to remain behind and join others in prayer in Rome. As they do so, a highly symbolic crack cuts through the depiction of creation in the Sistine Chapel, separating God the Creator from Adam his creation.

The message of the movie is that science is the force truly capable of detecting and predicting imminent disaster, and the only place to look for a solution, however meager it may be. Yet in proclaiming this message, the movie nevertheless echoes religious themes and even plays into the hands of so-called literalist interpretations of the Bible. The movie 2012 seems to imply that a global flood (or at least a tsunami) reaching the highest mountains is scientifically feasible. It offers arks filled with animals and people as a solution. It even alludes to the theme of creation being undone and redone as found in Genesis, for instance when the year when the ark can be opened is designated “Year 0001.”

The message of the movie is that science is the force truly capable of detecting and predicting imminent disaster, and the only place to look for a solution, however meager it may be. Yet in proclaiming this message, the movie nevertheless echoes religious themes and even plays into the hands of so-called literalist interpretations of the Bible. The movie 2012 seems to imply that a global flood (or at least a tsunami) reaching the highest mountains is scientifically feasible. It offers arks filled with animals and people as a solution. It even alludes to the theme of creation being undone and redone as found in Genesis, for instance when the year when the ark can be opened is designated “Year 0001.”So what is the appropriate thing for scientifically-informed individuals, almost as far removed in time from the Biblical version’s composition as that version was from the origin of the story that inspired it? Perhaps it is better to go even further, and retell the story as Roland Emmerich does in 2012, replacing a personal but angry and perhaps even cruel God with unfeeling nature. It is one thing to say that “God is not benevolent” and quite another to talk of nature, or of an underlying rational principle of nature, in this way, as the Daodejing does when it says “”Heaven and earth are not benevolent, and treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs.” While some view the shift away from personalized, anthropomorphic thinking about God as a departure from an essential element of the Judeo-Christian tradition, there is a sense in which this is a natural progression along a trajectory that begins before the ancient Mesopotamian flood epic and continues through the Priestly source’s creative reworking of earlier notions about God, creation and flood. Where once we had multiple personified forces of nature, Israel rolled them into one, a singular Elohim, responsible for all that happened, whether good or evil. Is there not something fitting about carrying on the process and recognizing that we do not need to posit a personified actor, much less a multiplicity of them, in order to account for things that happen? Might it be simply another step along the Biblical trajectory to adopt the stance of so-called “radical theology” and treat God and the Universe as at least overlapping, if not identical?

I suppose the big question is what one thinks about this psychologically, theologically and even pastorally. If there were a global catastrophe of the sort depicted in Noah or in 2012, would you take greater comfort from believing that a mighty God was doing it for a reason, or would it be more comforting to believe that there are no such powerful and capricious wills that may send torments upon humanity at a whim, even though that leaves you at the impersonal “whim” of forces of nature? As food for thought, I leave you Thomas Hardy’s famous meditation on this subject, his poem “Hap”:

Hap, by Thomas Hardy

IF but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: “Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy,

That thy love’s loss is my hate’s profiting!”Then would I bear, and clench myself, and die,

Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited;

Half-eased, too, that a Powerfuller than I

Had willed and meted me the tears I shed.But not so. How arrives it joy lies slain,

And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?

–Crass Casualty obstructs the sun and rain,

And dicing Time for gladness casts a moan….

These purblind Doomsters had as readily strown

Blisses about my pilgrimage as pain.

Most people are well aware that the sheer weight of geological, textual, comparative and other considerations indicate clearly that the story of Noah can no more be taking as literally historical or factual than can the story of Utnapishtim. The harder question for many of us is whether the theology of the flood story is not every bit as much something that we need to move beyond – even those of us who in many respects are heirs of the Israelite tradition that bequeathed the story to us.