Spring seems to have finally arrived warm and sunny. Each year brings a new surprise and this year shall be remembered for the extraordinary brightness of color in the plumage of birds we have seen. The gold finches, scarlet finches, cardinals and red breasted grosbeaks are noticeably brighter than in years past. The clear skies and bright colors of birds and flowers is how we often think of spring.

It may therefore seem a little odd then that in the Religio Romana the month of May is devoted to the spirits of the dead. May does begin with the festival of Florialia, which traditionally begins when the sun enters the fourteenth degree of Taurus. In ancient Rome Floralia was celebrated with much the same revelry seen with spring break today. Drinking, public nudity, and love-making, along with theater, the release of deer and rabbits, everything one would expect of a spring festival. But soon after the month’s celebration took on a more solemn tone.

The Roman month of Maius was said, in one account, to have been named for the Maiores, which is another way of saying our deceased ancestors. Another account attributes Maius as a name used for Jupiter at Tusculum. It may have indicated Jupiter as the Father of a man’s genius, and thus as that which lives on after death. The main festival of May is Lemaria held on 9, 11, and 13 May, while other days of the month celebrated the Rosalia that honored dead soldiers. Lemuria is not for just any spirits of the dead. The general term for the dead is Manes, meaning “the good ones.” Among the Manes are our Lares who are the spirits of deceased family members, or who sometimes refer to the spirits of those who have died and remain to protect our neighborhoods, roads, and other community places. Then, too, are the evil Manes, known as the Larvae. The Larvae are said to haunt deserted placed, dark bends in the road, and desolate wastelands. Lemuria is a festival held for those spirits of the dead who are not evil, but who are also not family. When someone dies without heirs to care for their rites, they roam the land as Lemures, searching for someone, anyone, to take them into their homes as Lares. (Yes, the lemures of Madagascar were named after these Roman Lemures due to their “ghostly” appearance.) The Lemures may not be evil, but they also cannot be certain to be friendly either, since they are not family or countrymen. Thus the idea of Lemuria is to provide something for them on their travels, but not enough to cause them to linger.

Rising just after midnight on the first night of Lemuria, a man, for it is he man of the house who is suppose to perform this ritual, performs a ritual for his Lares at the lararium, calling upon them to assist him in this night’s task. He then moves throughout the house while barefoot and not bound by any belt or ties. Nine dried beans are placed in his mouth. Both hands are raised in the sign of the fica with the thumb thrust through clenched fingers. The fica, or ‘fig,’ represents the protruding clitoris of Mater Manua, Mother of the Manes. By this gesture, and the bare feet, She is called upon for protection against any unwanted Manes who may have entered the house. One washes his hands and then casts some beans with his left hand over his left shoulder while looking forward; then he turns his head, averting his face to the right, as he raises the palms of both hands against the left as he says, “Haec ego mitto, his redimo meque meosque fabis.” (“‘With these beans I throw, I redeem me and mine.”) He does this nine times, covering every floor, if not every room in his house. Then washing his hands once more, he clangs a gong while shouting nine times “Manes, exi paterni!” (“Ancestral spirits, depart!”)

The rites continue into the daytime hours with the women and children cleansing and purifying the house further. I recall as a child, in my years before I went to school, how my mother would rush us indoors before sunset on these days. She would lock the doors, pull down the shades, turn mirrors to the walls, do everything to prevent the Lemures from seeing us, for, as we were told, if the Lemures saw us, they would carry us away. Then my bisnonna would gather us children to have us bang pot lids, rather than the gong of Temesan bronze that Ovid described, and howl like wolves, joined by neighborhood dogs, to frighten the Lemures away. Meanwhile my grandmother would spin about, dispersing boiling water all around the room with a wooden ladle . The water sometimes splattered onto us, making us howl all the more.

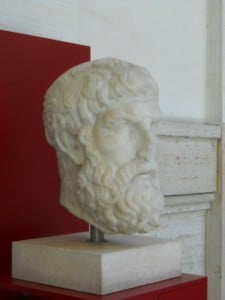

Where some of the rites of Lemuria are intended to dispel unwanted Manes and the evils they bring into the house, other rites invite the Lares to remain and bless the home. Having cleaned the house, it is then decorated with fragrant flowers. Offerings are left at the lararium for the ancestral spirits. Bowls of water with which to wash are set out for the Lares, as well as small towels. Bread, flour, salt, olive oil, honey and milk, incense and flowers, with perhaps some candles, were traditional offerings given by the Romans. Other things offered in my family were pebbles, stones, feathers, small statues, violets and wild flowers, trinkets and just about anything found that was unusual or colorful, like the smooth-edge shards of broken glass washed up on the shores of the lake. Images of the Lares are also brought from the lararium to the dining table for the family meal. Today they might be photographs of our deceased family members, where as the Romans may have used the busts or death masks that they kept of their ancestors.

An extra place is set for the Lares just as is done at a seder at Passover in Judaism. Their plate would be passed around the table for everyone to offer a portion of their meal, and libations of wine would likewise be poured for the Lares. After the meal, if not held outdoors, these offerings would be taken to a special place for burial. Here the family’s ancestors are invited into a welcoming home, to remain as Lares if they will. They are addressed and treated in the same manner as though they are your grandparents, for in a sense the Lares are just that. They are honored every morning, every evening, and at the phases of the moon each month.

Now that we have chased out the unwanted Manes from the house, and invited in our Lares to remain, there remain the Lemures. Whatever has fallen to the floor during the meal with the Lares is careful swept up and brought outside for them. Rather than a place set, offerings for the Lemures are provided on pottery shards, or broken china. The bowl of water is accompanied with a ragged towel. Flour, bread, salt, olive oil, and milk or water is left for the Lemures at a crossroads where one street or alley dead ends into another. Other gifts might be offered as well, like pebbles or copper coins, but nothing too good, and not too much. Maybe fruit and vegetables, but not meat. The idea is to show the Lemures the respect that is their due, but not make things so well for them that would wish to remain. They are to be sent on their way.

Then again, you might have some Lemures who you would wish to stay around to assist you. Since they are not family, and you wouldn’t want to invite unknown Lemures into your home, a place may be set up for them outdoors. At right is a little shrine for the Manes. Just a small pile of stones, and a crudely carved image is here to mark the spot. In front of it offerings have been buried over in a fire pit. Weeding the garden, they too are pile before this shrine. The Manes are called upon to carry away the spirit of the weeds, in hopes they won’t return. Likewise when the house is purified each month, what has been swept up with the grain offering is buried outside in front of the Manes. And then with a libation of wine, and maybe some of the juices from meat, they are called upon to remove whatever ills and impurities were expelled from the house.

There are different categories of Manes. Each have their place, and each are given their due. Some belong within the home, some in public places, others on the roads where they travel, and some in the fields and gardens. How one treats with each kind differs somewhat. But in that way we define our relationships with the dead just as we do with the living. And for each of them our prayers ask that they may enjoy an eternal spring on the Blessed Isles across the western seas.