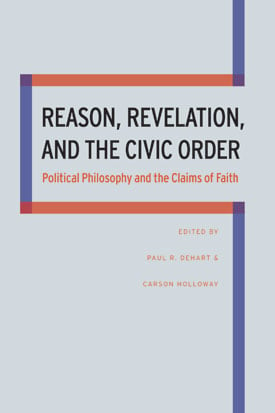

Northern Illinois University Press has just published Reason, Revelation, and the Civic Order: Political Philosophy and the Claims of Faith. Edited by Paul DeHart (Texas State University) and Carson Holloway (University of Nebraska, Omaha), I am proud to be one of the contributors along with  Peter Augustine Lawler (Berry College), Robert C. Koons (University of Texas), J. Budziszewski (University of Texas), James Stoner, Jr. (Louisiana State University), R. J Snell (Eastern University), Ralph C. Hancock (Brigham Young University), Micah Watson (Union University), and Lugi Bradizza (Salve Regina University).

Peter Augustine Lawler (Berry College), Robert C. Koons (University of Texas), J. Budziszewski (University of Texas), James Stoner, Jr. (Louisiana State University), R. J Snell (Eastern University), Ralph C. Hancock (Brigham Young University), Micah Watson (Union University), and Lugi Bradizza (Salve Regina University).

Here’s the book’s description from the publisher’s website:

“What has Athens to do with Jerusalem? When it comes to politics, a great deal, as the superb set of essays DeHart and Holloway have gathered show so well. In these pages the political is nourished by the theological, something we sorely need today.”-R. R. Reno, Editor, First Things

“Religion is typically regarded by contemporary political philosophers as a problem. It’s a problem for the state, since religion threatens oppression and violence; and it’s a problem for political theorists themselves, since religion is held to be irrational and its intrusion into political thought would corrupt the pure rationality of acceptable political theory. The authors of this collection, while agreeing that religion can be a problem, argue persuasively that it is also a resource, both for our life together and for our theorizing, a resource that we neglect at our peril. It’s a bold and courageous book, contesting the pieties of our present day. ”-Nicholas Wolterstorff, Yale University

While the dominant approaches to the current study of political philosophy are various, with some friendlier to religious belief than others, almost all place constraints on the philosophic and political role of revelation. Mainstream secular political theorists do not entirely disregard religion. But to the extent that they pay attention, their treatment of religious belief is seen more as a political or philosophic problem to be addressed rather than as a positive body of thought from which we might derive important insights about the nature of politics and the truth of the human condition.

In a one-of-a-kind collection, DeHart and Holloway bring together leading scholars from various fields, including political science, philosophy, and theology, to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy and to demonstrate the role that religion can and does play in political life.

My 30-page chapter, entitled “Fides, Ratio, et Juris: How Some Courts and Some Legal Theorists Misrepresent the Rational Status of Religious Beliefs,” offers a critical analysis of what I call Secular Rationalism (SR), a view embraced by several notable legal theorists including Suzanna Sherry (Vanderbilt University), Brian Leiter (University of Chicago), and the late Stephen Gey (Florida State University). Here is how the chapter begins (endnotes omitted):

Religious citizens, like their nonreligious compatriots, attempt to shape public policy in order to advance what they believe is the common good. Critics have suggested that there is something untoward with such activism, since the positions advocated by these citizens are informed by their religious beliefs. Some of these critics ground this judgment in the claim that religious beliefs are by their very nature not amendable to rational assessment and are thus irrational.

This view should not be confused with what is sometimes called Political Liberalism and often associated with the work of John Rawls and his numerous disciples. According to that view, policies informed by religious or secular comprehensive doctrines that limit the fundamental liberties of citizens who do not share those comprehensive doctrines are justified if and only if the coerced citizens would be irrational in rejecting the coercion. Rawls, himself, concedes that many of these comprehensive doctrines, including the religious ones, are reasonable. This is why Rawls distinguishes between reasonable comprehensive doctrines and the grounds by which the government may be justified in coercing its citizens.

The focus of this chapter will be on those who eschew Rawls’ modest approach and argue that all religious worldviews are at their core unreasonable, because they are dependent on beliefs not amendable to reason. The implication of this view–that some, though not all, proponents of it explicitly acknowledge—is that religiously informed policy proposals have no place in a secular liberal democracy that requires the primacy of reason. Although this view of religion’s rationality is found or implied in several US Supreme Court opinions as well as among some legal and political theorists, it is far more controversial than its advocates portray.

You can order the book from Amazon.com or the publisher, Northern Illinois University Press.