I confess that Richard Beck is one of my favorite contemporary thinkers. He’s an experimental psychologist by profession, but is one of the very few brave souls who crosses fields (psych and theology) and does serious interdisciplinary reflection. This makes him one of the most important voices for contemporary theology today, in my opinion.

I was looking forward to receiving his most recent book, The Slavery of Death, and have finally had a chance to take a look at it. I will probably post a series of blog reflections on this, so I’ll start with his opening claim:

Death, not sin, is the primary predicament of the human condition. Death is the cause of sin. More properly, the fear of death produces most of the sin in our lives (3).

As Beck goes on to show, this is a complete reversal of the way most western Christians have been trained to think about the  relation between sin and death. This is particularly true for fundamentalists, evangelicals and others who are accustomed to reading the Genesis creation story as literal and historical. In Genesis 3, the serpent and God both seem to agree that the consequence of sin (eating the forbidden fruit) would result in death. But as Beck points out, whatever we make of that primal origin story, the situation of Eden is no longer our situation. In our situation, death (and our existential/psychological awareness of it) precedes sin in that it is the pervasive, ominous backdrop to sin; the universality and inevitability of death creates the conditions under which sin emerges in the human experience. All of this presumes, I believe anyway, that we need to rid ourselves of Augustine’s theory of original and inherited guilt–for Augustine’s theory (based on a faulty interpretation of Romans 5 and psychologically related to his own personal and existential guilt) has so embedded itself in the Protestant theological imagination that we cannot but think of sin as the cause of death. This interpretation of “the Fall” is nearly impossible to shake. That is, until we consider the alternative.

relation between sin and death. This is particularly true for fundamentalists, evangelicals and others who are accustomed to reading the Genesis creation story as literal and historical. In Genesis 3, the serpent and God both seem to agree that the consequence of sin (eating the forbidden fruit) would result in death. But as Beck points out, whatever we make of that primal origin story, the situation of Eden is no longer our situation. In our situation, death (and our existential/psychological awareness of it) precedes sin in that it is the pervasive, ominous backdrop to sin; the universality and inevitability of death creates the conditions under which sin emerges in the human experience. All of this presumes, I believe anyway, that we need to rid ourselves of Augustine’s theory of original and inherited guilt–for Augustine’s theory (based on a faulty interpretation of Romans 5 and psychologically related to his own personal and existential guilt) has so embedded itself in the Protestant theological imagination that we cannot but think of sin as the cause of death. This interpretation of “the Fall” is nearly impossible to shake. That is, until we consider the alternative.

So what if it’s the other way around? What if death (and our awareness of it) creates the conditions for our sin? What if sin is a consequence of death?

This alternative, Beck suggests, reflects an Eastern Orthodox reading of the creation and Fall account. In Eastern theology, the Fall story is less about the origin of sin than it is about the origin of death. It is a theodicy–a theological explanation of the presence of death and suffering–rather than a soteriology–an explanation of the origin of sin (p. 5). The serpent (understood in much early subsequent theology as representing the devil or Satan) was there in the garden before the first sin ever occurred. The serpent was then responsible for bringing death into the world.

But it’s not just the devil or Satan: human beings were (and continue to be) responsible for summoning death. As Beck puts it,

Adam and Eve summoned death and we, in word and deed, recapitulate their sin and thus continue to summon death. We live life controlled by a ‘covenant with death.’ In the language of Hebrews 2:15, we are ‘slaves to the fear of death.’ (6)

The situation of our slavery to death goes a very long way in helping us to understand the historical and present human condition. We are driven to and fro by our anxiety about death, sometimes consciously and very often unconsciously. We compete for scarce resources (sometimes to the death!), we compete for promotions, we construct lives that suppress our anxieties about death (sometimes in healthy ways, sometimes in very pathological ways). Our relational lives are very often determined by the way we interact internally with our own fears and anxieties about our inevitable, future demise. What we have received from our human forebears, then, is less a “moral stain” than a “mortal condition.” It is death that gives rise to sin. And sin is a deeply and intricately relational phenomenon. It is not surprising that, following the banishment from the garden, the very next sin story in the Bible is murder–motivated by jealousy and (very likely) Cain’s own psychological death anxiety.

This little reflection on the very beginning of Beck’s book just scratches the surface, so I hope to continue blogging on this in coming weeks. A major question that is already raised in my mind is how evolution fits into the “theodicy” approach to Gen. 3? If we accept evolution as the scientific “origin story” of creation and the human species, where does the “devil/Satan” fit? And how are we to understand human beings “summoning death” when the death of sentient life was already around for millions of years?

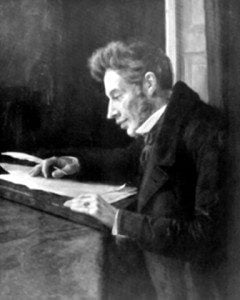

In March I will present, at what looks to be a great conference on the psychology of religion, some of my own work on Ernest Becker’s use of Kierkegaard in Becker’s Denial of Death. Kierkegaard has some remarkably prescient things to say about the relation between human anxiety and death. He explicitly wrote about death anxiety in parts of his corpus (the Edifying Discourses) of which Becker was not apparently aware. And Kierkegaard drew on the words of another important theologian to do so. “Consider the birds…”

Image Credit: photo credit: <a href=”https://www.flickr.com/photos/cindyfunk/2039927711/”>Cindy Funk</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>cc</a>