Excerpts from Atlanta’s Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory’s homily at the Immigration: The Facts, the Challenges, The Moral Response Conference this past December 4th. For the full homily text, click here.

“The role of the Catholic Church in the current immigration debate in the United States has surprised and perhaps upset many people, including even some Catholics. But the Church’s position on migration has remained consistent for decades. Drawing on some classic principles of Catholic social thought, the bishops of the Church have expressed our opposition to the breaking of laws and unlawful entry into the country. The Church has long acknowledged the right of a nation-state to control its territorial borders and to regulate entry.”

“The State has a very serious responsibility to protect its citizens and this may entail strong immigration controls. At the same time however, the Church says that human beings have a right to migrate – particularly in search of work in order to improve their human condition and to provide for the needs of their families.”

“Let me trace for you how the Catholic Church and in most cases other religious communities have arrived at these public policy positions on immigration. It would be misleading to view the Church as just another pro-immigration special interests lobby. While the starting point of analysis for the government as well as for most advocacy groups is the law or economics, the Church sees the issue of migration through a much richer prism of global history, Judeo-Christian spirituality, social reflection, theology and extensive pastoral experience. Legal and economic categories for classifying migrants – such as “economic migrants”, “asylum seekers”, “illegal immigrants” – while recognized by the Catholic Church, are not the primary ways that the Church relates to migrants. She does not ask first whether a person is legal or illegal, but rather looks at the migrant as a human person within the human family. Legal status is simply one of the many dimensions that the Church sees in the person of the migrant.”

“The Catholic Church is a global religion. The Church in the United States is organically part of the same Catholic Church in, for example, Mexico. So the Church sees migration from both sides of the border. Its transnational identity as a faith community demands that its pastoral care transcend political boundaries. Its pastoral mission can never be fully restricted to a single sovereign state. The Church has always had this global pastoral mission and that mission is what gives the Catholic Church its particular perspective on migration.”

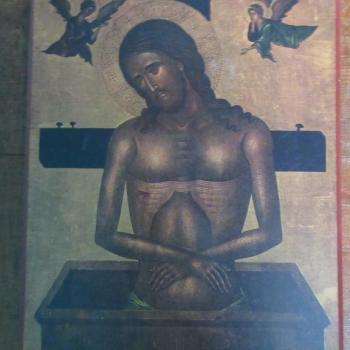

“Christianity rooted itself squarely in that same [Jewish] tradition. The moment that Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew identifies himself with the alien, with the stranger – if you welcome the stranger, you welcome me – the followers of Christ are charged with adjusting their normal perspective. If Christ himself is the stranger, the Church of Christ must have a special concern for migrants who are always the strangers in our midst.”

“The Gospels are full of migration stories. Think of the birth of Christ, consider the family as refugees in Egypt, the journeys to Jerusalem, Jesus himself was an itinerant preacher, rejected by his home town, with – as he says – “no place to rest his head”. It was Jesus who created the missionary impulse in his followers, the globalizing tendency of Christianity, that St Paul’s travels epitomized. It is not surprising that one of the earliest names for Christianity was the ‘Way’ or the ‘Road’.”

“In light of the Gospel, it was not much of a leap for the early Church Fathers to interpret the following of Christ —Christian spirituality – as a journey, a migration of the human spirit.”

“By the time of Augustine of Hippo the identification of Christians with migrants was well established. For Augustine the world is, not unlike our own contemporary world, a dangerous and chaotic place. Christians, he said, are simply passing though this life as “resident aliens”. This world is not our true homeland. Our real citizenship is in the City of God. So from the Augustinian perspective, Christians would have a natural, almost ontological empathy for the migrant stranger. In fact migration is a symbol of the way the Church should view itself. This idea of the “Pilgrim Church” re-surfaced at the Vatican II Council.”

“Some of this reflection came to be codified in the late 19th and 20th centuries through official papal documents that have come to be called Catholic social teaching. The Holy See recently published a Compendium of Catholic Social Doctrine which brings together many of these papal insights around the core concepts of the common good, subsidiarity, solidarity and promotion of the dignity of the human person. Each of these complex concepts has applications in the area of migration but the dignity of the human person seems to have particular relevance to the treatment of migrants.”

“Pope John Paul II was fond of pointing out that just labor – work – was essential to human dignity. The Church believes that all human beings have a right to work and to a just wage. As a corollary to this, Pope Pius XII said that people have a right to migrate in search of work. Human dignity, jobs, human rights and migration are linked in the mind of the Church. As the German thinker, Karl Lowith wrote: “Any one having a human face has human dignity and a human destiny”. For the Church, there is no neutrality on this question. It impregnates and illuminates all Christian understanding of social life. Protecting that human value stands at the heart of the Church’s role in society.”

“The Church has always understood that the experience of migration can result in a new relationship to God and a deeper understanding of our human nature. Migrants and refugees bear many gifts of the spirit. But especially today, migration can be a time of human diminishment – not only through the horrors of sex trafficking, modern enslavement, and forced labor but in the smaller, less noticed, ways that migrants are demeaned – by being reduced to a statistic, a work force, or a legal category. Christians are called by Christ to humanize those statistics, that work force and those legal categories. In many ways the Church’s perspective really balances the perspective of governments which have to make the difficult decisions about who is allowed to enter the country. It is unfortunate that the current public debate on immigration in the United States has become so coarse and polarizing. I could envision another kind of public dialogue where the centuries-old experience of Christianity can help balance the hard exigencies of law, where we can realistically protect the common good of our citizens while reclaiming our heritage as a society that welcomes the stranger. This value echoes through the religious thought of three [Islam, Judaism, and Christianity] great families of Faith.”

Emphasis added.