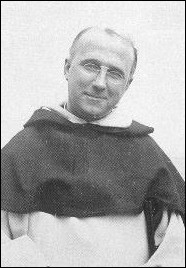

Part 2: A Brief Look at Henri de Lubac

In this, my third and final installment on the Ressourcement movement in Catholic theology, I wish to briefly sketch the impact and historical endurance of the movement. While Henri de Lubac m ay rightly be described as the centerpiece of Ressourcement, he most certainly was not alone in infusing its spirit into Catholic life and thought. Rather, he was flanked by a number of confreres in theology and philosophy which ensured that this spirit remained embodied in theology and philosophy alike.[1]

ay rightly be described as the centerpiece of Ressourcement, he most certainly was not alone in infusing its spirit into Catholic life and thought. Rather, he was flanked by a number of confreres in theology and philosophy which ensured that this spirit remained embodied in theology and philosophy alike.[1]

As has been mentioned, the spirit of Ressourcement may be succinctly described as a return to the first interpreters of Christian revelation, the Church Fathers, so as to rediscover and revitalize the essence of Christianity in the midst of Europe’s modern crises of faith. Therefore, contrary to the perception of many of its detractors from both within and without Catholic theological circles, Ressourcement was neither a simple exercise in some sort of theological archeology nor a nostalgic admiration of bygone eras. Ressourcement was responding to two chief trends in 20th century Europe: 1. the ossification of Catholic theology due to the manual tradition of Neo-Scholasticism, which had (a) deemed itself the only proper philosophical response to modern philosophy’s preoccupation with subjectivity and ideas, and (b) claimed that, through Thomas Aquinas and the commentary tradition, it had extracted and unified the best teachings of the Fathers and Scholasticism, establishing itself as science; 2. the increasing disappearance of the sense of the sacred in European consciousness due to (a) secularizing post-Enlightenment trajectories, and (b) the increasing irrelevance of the Christian worldview on account of liberal Protestant theology and Catholic Neo-Scholasticism.

The earliest efforts of that loose band of theologians whom we call Ressourcement thinkers have proven to be among the most enduring in Catholic theological studies. As early as 1942, the French Jesuits Henri de Lubac and Jean Daniélou had inaugurated the Sources Chrétiennes project, which sought to make available to the Francophile world fresh translations and critical editions of the writings of the Western and Eastern Fathers of the Church. The project continues today, having published its 500th translation and critical edition in May 2006.

It was the early recovery and re-appropriation of the genuine Thomistic and Augustinian theologies of nature and grace through the efforts of de Lubac[2] and Henri Bouillard[3] that set the terms of the debate with Neo-Scholasticism on the one hand, and with ‘transcendental Thomism’ on the other. This latter debate continues today, though it appears that the theology of grace and nature as developed by Rahner and his disciples is beginning to fade due to its marked Suarezian base and its haphazard—or should I say schizophrenic—oscillation between Neo-Scholasticism and a poor interpretation of Martin Heidegger’s ‘existential’ phenomenology. On account of the efforts of de Lubac and Bouillard, the theology of grace has not gone out of style in Catholic theology and continues to be of interest to contemporary theologians.[4]

In 1946, Ressourcement had become a well recognized and, depending on who was asked, a rather notorious forc e in Catholic theology. If de Lubac’s Catholicisme (1938) may be called Ressourcement’s programmatic essay, Jean Daniélou’s 1946 essay “Le orientations présentes de la pensée religieuse” was its manifesto.[5] In this remarkable essay, Daniélou discussed three elements in current theology: 1. The spirit of Ressourcement as a return to early Christianity so as to revive biblical, historical and liturgical studies; 2. The need for Catholic theologians to dialogue with modern philosophy on the latter’s terms, employing the tools and ideas recovered through Ressourcement; 3. The gross need to move beyond the prevailing Neo-Scholasticism and its ahistorical and hermeneutically numb attempts at systematization. Needless to say, the thinkers associated with the early Ressourcement movement, especially de Lubac, Bouillard and Daniélou, drew the ire of many Neo-Scholastics of the day, most notably that of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange and Marie-Michel Labourdette. It would be Garrigou-Lagrange who, expressing both disapproval and dismay, would coin what would become the lasting caricature of Ressourcement: “la nouvelle théologie”.[6]

e in Catholic theology. If de Lubac’s Catholicisme (1938) may be called Ressourcement’s programmatic essay, Jean Daniélou’s 1946 essay “Le orientations présentes de la pensée religieuse” was its manifesto.[5] In this remarkable essay, Daniélou discussed three elements in current theology: 1. The spirit of Ressourcement as a return to early Christianity so as to revive biblical, historical and liturgical studies; 2. The need for Catholic theologians to dialogue with modern philosophy on the latter’s terms, employing the tools and ideas recovered through Ressourcement; 3. The gross need to move beyond the prevailing Neo-Scholasticism and its ahistorical and hermeneutically numb attempts at systematization. Needless to say, the thinkers associated with the early Ressourcement movement, especially de Lubac, Bouillard and Daniélou, drew the ire of many Neo-Scholastics of the day, most notably that of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange and Marie-Michel Labourdette. It would be Garrigou-Lagrange who, expressing both disapproval and dismay, would coin what would become the lasting caricature of Ressourcement: “la nouvelle théologie”.[6]

The talk of a “new theology” fermenting among the French Jesuits no doubt left many in the Roman Curia uneasy. The prominence of Garrigou-Lagrange in Rome ensured that Pope Pius XII would catch word of the development. In 1950, the encyclical Humani Generis was promulgated in resp onse to a number of troubling scientific, political, philosophical and theological trends in Europe. The encyclical made a cryptic reference to a “new theology” and the effort of some to destroy the gratuity of grace. While Humani Generis made no explicit reference to de Lubac or his confreres, many ecclesiastics and academics interpreted (wrongly) the encyclical as a condemnation of their efforts. After the promulgation of Humani Generis, the Superior General of the Jesuits ordered the removal of all of de Lubac’s books from Jesuit libraries and asked him to step down from his teaching position. Many others mistakenly took the encyclical as a censure of de Lubac’s positions and kept their distance from him. Daniélou and, to a lesser extent, Bouillard were also looked upon with suspicion. However, de Lubac would be vindicated when he was called by Pope John XXIII in the late 1950’s to help prepare the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).[7]

onse to a number of troubling scientific, political, philosophical and theological trends in Europe. The encyclical made a cryptic reference to a “new theology” and the effort of some to destroy the gratuity of grace. While Humani Generis made no explicit reference to de Lubac or his confreres, many ecclesiastics and academics interpreted (wrongly) the encyclical as a condemnation of their efforts. After the promulgation of Humani Generis, the Superior General of the Jesuits ordered the removal of all of de Lubac’s books from Jesuit libraries and asked him to step down from his teaching position. Many others mistakenly took the encyclical as a censure of de Lubac’s positions and kept their distance from him. Daniélou and, to a lesser extent, Bouillard were also looked upon with suspicion. However, de Lubac would be vindicated when he was called by Pope John XXIII in the late 1950’s to help prepare the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).[7]

During the Second Vatican Council, the bishops voted overwhelmingly to scrap the various schemata prepared by the preparatory councils due to their archaic tone and stark dependency on Neo-Scholasticism’s outdated language and thought-forms. New constitutions were drafted under the aegis of a number of theological experts who had felt the heavy-hand of the Curia during the 1950’s: Henri de Lubac, Yves Congar, Edward Schillebeeckx and Hans Küng. What marked these drafts was an historical awareness of the development and pluralism of Catholic thought and liturgical practice across 1900 years. The Council began heading in a new direction, re-grounding the theology and liturgical life of the Church in the earliest Christian traditions stemming from the Fathers. The intention was to fortify the Church’s understanding of its foundations in order to respond to the modern world in terms that were both relevant and coherent. Thus, the work of the Second Vatican Council was largely shaped by the very spirit of Ressourcement. Ressourcement became virtually synonymous with the theme of the Council, aggiornamento—retrieval, restoration and renewal in the Church.[8]

After the Council, Neo-Scholasticism all but disappeared from the theological scene. At the risk of over-generalization, it may be said that Catholic theology largely followed two post-conciliar trajectories. On the one hand were a number of thinkers who interpreted the Council as sanctioning a thoroughgoing grounding of theology in the methods and manners of modern philosophy and/or historiography.[9] On the other hand was a number of thinkers who aligned themselves within the Ressourcement movement, and by extension, the truest spirit of the Council. These included, of course, the original members of the movement such as de Lubac, Daniélou and Congar, as well as a younger generation of thinkers who had been greatly influenced by their works. Most famous among them include Hans Urs von Balthasar, Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), Louis Bouyer and Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II).[10]

If there is any doubt that the Catholic Church did not favor the Ressourcement movement in its theological and liturgical life after the Second Vatican Council, one need only point to the ecclesial honors bestowed on its greatest proponents. Three of the Ressourcement thinkers who were pivotal in forming the theology of the Second Vatican Council were made Cardinals: Jean Daniélou in 1969, Henri de Lubac in 1983 and Yves Congar in 1994. Rarely are priest-theologians elevated to the College of Cardinals. The Ressourcement movement has proven itself to be far more enduring than other twentieth-century movements in Catholic theology. While many of the post-conciliar theological trends continue to lose their abilities to provide answers to the questions of contemporary philosophy and society, Ressourcement thought continues to exert a strong influence in contemporary theology and Christian life. A few examples of this will suffice.

Since the early 1970’s, the pioneering Catholic theological journal Communio, which was founded by de Lubac, Ratzinger and Balthasar in order to aid in the interpretation, implementation and expression of conciliar theology, has been a major force in contemporary scholarship. Not only does the journal publish articles by contemporary theologians influenced and marked by the Ressourcement style, but it also reprints a number of short and scarce pieces by the major thinkers associated with the movement.

Henri de Lubac continues to be read and studied by specialists and non-specialists alike. In recent years, many of his ideas have been appropriated by the Radical Orthodoxy movement due to their recovery of the Neo-Platonist, Origenist, Augustinian and Scotist themes in the history of Christian thought that were typically forgotten or ignored by Neo-Scholasticism’s triumphalism and pageantry.

Hans Urs von Balthasar’s recovery and development of the primacy of beauty among the Scholastic transcendentals has provided Catholic thought with a certain resiliency in the face of post-modernity’s sweeping critiques of modernity and its (dis)contents. Balthasar has become a pivotal figure in contemporary theological and philosophical discussions within and without Catholic circles.

Finally, Jos eph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, has ensured the incorporation of Ressourcement theology in the Catholic doctrinal tradition. Less speculative than Balthasar and more philosophically and politically conscious than de Lubac, Ratzinger’s theology has been a constant address to, and discourse with, modern and contemporary philosophy and politico-social theory.

eph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, has ensured the incorporation of Ressourcement theology in the Catholic doctrinal tradition. Less speculative than Balthasar and more philosophically and politically conscious than de Lubac, Ratzinger’s theology has been a constant address to, and discourse with, modern and contemporary philosophy and politico-social theory.

To conclude, it is worth repeating that Ressourcement never meant to remain an exercise within academic theology. On the contrary, Ressourcement was a spirit that found haven in a number of independent, diverse men of deep Christian conviction who possessed the understanding that Catholicism needed to rediscover its very core in order to survive in the shifting boundaries of Europe’s intellectual and political landscape. This necessitated a theology that was informed by its past so as to address the present, and a theology that was nourished simultaneously by its intellectual merits and its spiritual heritage. Ressourcement theology is a theology can be lived in prayer, in society and in academia. For this reason alone, it exposed the inadequacies of arid Neo-Scholasticism, it outlives its post-conciliar peers, and it will continue to inspire the whole of Christianity in a post-modern, post-religious world.

Notes:

[1] Abutting Ressourcement theology was the work of Maurice Blondel, Marie-Dominique Chenu and Étienne Gilson, all of whom possessed an acute sense for historicity and hermeneutics in philosophical investigation.

[2]Among Henri de Lubac’s major works on the nature/grace debate were Surnaturel (1946) [no English translation], Augustinisme et théologie moderne (1965) [ET: Augustinianism and Modern Theology, trans. Lancelot Sheppard (1969; reprint New York: Crossroad, 2000)], Le Mystère du surnaturel (1965) [ET: The Mystery of the Supernatural, trans. Rosemary Sheed (1967; reprint New York: Crossroad, 1998)], and Petite catéchèse sur nature et grâce [ET : A Brief Catechesis on Nature and Grace, trans. Richard Arnandez (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1984)]. It may be worth noting that, in his recent book on de Lubac and the ‘debate on the supernatural’, John Milbank does not once reference de Lubac’s last word on the issue, Petite catéchèse sur nature et grace. See John Milbank, The Suspended Middle: Henri de Lubac and the Debate concerning the Supernatural (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005).

[3] Among Henri Bouillard’s major contributions on the question of grace were Conversion et grâce chez S. Thomas d’Aquin (1944) [no English translation] and Blondel et le Christianisme (1961) [ET: Blondel and Christianity (Cleveland: Corpus, 1969)].

[4] Three recent books on this very topic are worth mentioning here: Stephen J. Duffy, The Graced Horizon: Nature and Grace in Modern Catholic Thought (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992); Lawrence Feingold, The Natural Desire to See God According to St. Thomas Aquinas and His Interpreters (Dissertationes, 3; Rome: Edizioni Università della Santa Croce, 2001); John Milbank, The Suspended Middle.

[5] Published in Étudies 249 (1946): 5-21.

[6] The term was first used by Garrigou-Lagrange in his inflammatory and polemical essay, “La nouvelle théologie, où va-t-elle?”, Angelicum (1949): 126-45.

[7] De Lubac was joined by another theologian whose work was likewise suspect during the pontificate of Pius XII, Yves Congar. After the Second Vatican Council, both de Lubac and Congar would speak of the contempt and alienation they experienced prior to the Council’s proceedings due to the Neo-Scholastic dominated preparatory commission.

[8] The impact of Ressourcement is most acutely evidenced in the conciliar documents Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church), Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation), Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World) and Nostra Aetate (Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions).

[9] This is not to suggest that these thinkers comprised a monolithic trend in Catholic theology. Under the single banner of “pluralism” these thinkers followed a number of different paths in theology.