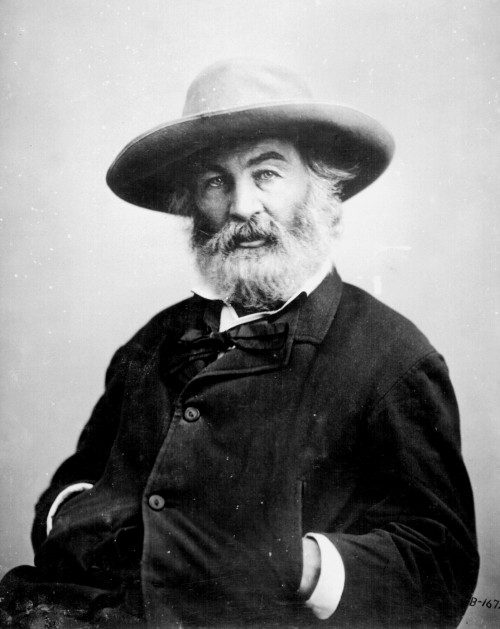

In my neck of the woods, the name Walt Whitman is associated with a bridge that connects the southern part of Philadelphia with Camden, New Jersey. You’ll usually hear about “the Walt Whitman” in connection with traffic jams or lane closures. But while reading Mary Oliver’s Upstream, I was reminded that the real Walt was perhaps our greatest American poet.

In 1855, at the age of 37, Whitman first published what was to become his masterwork, Leaves of Grass. He kept working on the poem for four decades, rewriting and adding to it over and over, until by 1892 it had grown from 12 poems to over 400.

Oliver describes Leaves of Grass as “a way to live, in the religious sense, that is intelligent and emotive and rich, and dependent only on the individual…no politics, no liturgy…just attention, sympathy, empathy.” She writes that Whitman’s aim was to “force open our souls” which he does with calls-to-arms like this:

Unscrew the locks from the doors!

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jams!

Whitman believed in God, and according to biographer David S. Reynolds “denied any one faith was more important than another, and embraced all religions equally.” Whitman himself once wrote “I adopt each theory, myth, god, and demi-god, I see that the old accounts, bibles, genealogies, are true, without exception“. He believed that God existed in all things and within all people, that we are God and God is us. In Leaves of Grass he explains:

I hear and behold God in every object, yet understand God not in the least,

Nor do I understand who there can be more wonderful than myself.

Why should I wish to see God better than this day?

I see something of God each hour of the twenty-four, and each moment then,

In the faces of men and women I see God, and in my own face in the glass

There are long passages in Leaves of Grass where Whitman offers glimpses of his America, his words taking us to the people and places that made up our country in the mid-1800s. He empathizes with what he sees, writing that “I know every one of you, I know the sea of torment, doubt, despair and unbelief.” Whitman observes and reports and, with an economy of words, paints vivid scenes with each line:

The conductor beats time for the band and all the performers follow him,

The child is baptized, the convert is making his first professions,

The regatta is spread on the bay, the race is begun, (how the white sails sparkle!)

The drover watching his drove sings out to them that would stray,

The peddler sweats with his pack on his back, (the purchaser higgling about the odd cent),

The bride unrumples her white dress, the minute-hand of the clock moves slowly,

The opium-eater reclines with rigid head and just-open’d lips

Whitman looked at the mosaic that is America and saw a country that was, like him, vibrant and alive. His lust for life, and his love and compassion for all that he encounters, becomes contagious. He believes we are all connected, with one another and with one God:

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers, and the women my sisters and lovers

He passes no judgment, all men and women he encounters are created equal, regardless of their station in life:

It is for the wicked just the same as the righteous, I make appointments with all,

I will not have a single person slighted or left away,

There shall be no difference between them and the rest.

Walt Whitman is a true man of the people, all people, and his fearless, open-hearted voice still resonates today. For more of my favorite passages from Leaves of Grass, with brief commentary, click on the Continue button below. Or to see the poem in its entirety, via the Poetry Foundation, click here.