After all, considering the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and the challenges in recent days, the State of Israel, the land of Palestine, and the various nations which surround what is often referred to as the “Holy Land” or “Levant,” are on our minds and in our news feeds more today than ever.

As with any story, this one has multiple sides to it.

And an honest assessment of the challenges of the region will require observers to take into consideration not just the politics of governments in the region, but also the plight of the people who are frequently the victims of the fallout which accompanies the wars and aggression that has been ongoing in that part of the world—really since the beginning of time.

Israel and Its Wars: A Short Historical Overview

LEARN MORE: A Brief History Of Israel And Its Conflicts

Dozens of books and hundreds of articles have been written on the history of the conflict and warfare in the region. In the short space we have here, we can’t possibly do justice to a retelling of that long and complex history.

So, what we’ll offer first is just a “birds-eye view” of the challenges the region has seen in its more than three-thousand years of recorded history. Some of the earliest disputes in that part of the world are only recorded in the Holy Books of the three so-called “Abrahamic religions.”

As a consequence, some readers may question the validity of those accounts. However, the Sacred Texts of Jews, Christians, and Muslims are not only the sole sources for some of what we know, but they are also foundational narratives that have been cited to justify much of the conflict in that part of the world.

Suffice it to say, from the time that Cain slew Abel, the land of Southwest Asia has seen innumerable conflicts. There were the early tribal conflicts of the “patriarchal period” (circa 1800 BEC), followed by Joshua leading the descendants of Jacob (also known as “Israel”) into battle against the peoples of Canaan (circa 1200 BCE). While there were skirmishes with a variety of regional powers under Kings David and Solomon, bigger challenges arose with the Assyrian (722 BCE) and Babylonian (586 BCE) captivities.

Additionally, when Alexander the Great conquered the Jews (332 BCE) and then the Roman Republic took power (in 63 BCE), the “Israelites” struggled to again gain self-governance. The Jewish revolt (66-73 CE) largely “sealed the deal,” pushing the majority of the Jewish residents of Jerusalem into other parts of Palestine and beyond.

The 7th century Muslim Conquest of Jerusalem, followed by the Crusades (11th-13th centuries), continued the upheaval in the Levant, even though the percentage of Jews living there was limited. The one real window of post-New Testament peace in the “Holy Land” took place during the Ottoman Era (1517-1917). Throughout that period, 400 years passed without any significant clashes in Jerusalem or the immediate vicinity.

However, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have seen near-constant conflict, from the 1948 Israeli War of Independence to the June 2025 clash between Israel and Iran. While many nations have seen war, the fact that the land of Israel/Palestine has been occupied and disputed essentially non-stop for so many centuries might be one explanation as to why that sacred soil has seen so much conflict.

The Role of Religion in the Conflict

Perhaps more than anything, religion is at the heart of the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict. No, not every war or skirmish in the Levant is verbally tied to religion but, so much of its modern conflicts are rooted in the fact that the “Holy Land” is sacred to three distinct (but related) religious groups, and that has inspired a not-so-holy zeal for literally millions of years.

Some of the most sacred sites in Jewish history are found in that region. For example, Solomon’s Temple, Zerubbabel’s Temple, and Herod’s Temple each occupied a portion of what Jew’s today call the “Temple Mount” (and which Muslims often refer to as Haram al-Sharif—or the “Nobel Sanctuary”). Indeed, Temple Mount was ranked the Top Holy Place in the world in Patheos’ Sacred Spaces project.t

For Christians, on the other hand, the region of Palestine and the city of Jerusalem are the places where their Messiah, Jesus, was born, taught, performed miracles, and ultimately died for His believing followers.

For Muslims, the location of the Dome of the Rock is not only the third most holy site in Islam, but it is also the location from which the Prophet Muhammed (PBUH) ascended up into heaven, receiving his calling as Allah’s final Messenger. Thus, for each of these three important religious traditions, Jerusalem (and the surrounding land) is as sacred as sacred can be.

In addition to the fact that so many important religious events took place in this remarkably ancient portion of the planet, there is also the challenge posed by the fact that many Jews and Muslims believe that their respective holy book promises the land of Palestine to the descendants of Abrahm/Ibrahim.

Judaism has traditionally taught that Isaac (Abraham’s second-born son, born to the ancient patriarch’s first wife, Sarah) was the person to whom God promised the inheritance of the “Holy Land.”

Islam, on the other hand, has long held that Ismā'īl (Ibrahim’s actual first-born son, birthed by Hājar, whom Muslims see as Ibrahim’s second wife) was the one God made inheritor of Palestine. In other words, setting aside the sacral nature of what has taken place in that land, both Jews and Muslims have scriptural precedent for their belief that this remarkably sacred land “belongs” (by divine design) to their people.

Again, while not every challenge that arises in the region between the various people who currently live there is verbally declared to be in the name of Allah, Jesus, or the “God of Israel," the tensions which exist between the various peoples living in that region are often tied up in the history of the land and the irrevocable promise of a God who is said to have assigned it to a specific group of believers.

Who is Thy Neighbor?

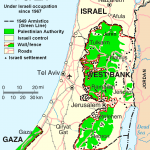

In an uncomfortable exchange, which ultimately led Jesus to teach one of His most famous parables (“The Good Samaritan”), Christ was asked (by a “lawyer”) “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29). That controversial question, posed by a man who was trying to find a way out of “loving” others, has significant bearing on why there is so much war in the Middle East. You see, the current State of Israel covers about 8630 square miles. Essentially, Israel is the size of the state of New Jersey.Bluntly put, Israel is “tiny” by any standards. (Out of the nearly 200 sovereign nations in the world today, only 14 are smaller than the State of Israel.)

And yet, that teeny strip of land (with nearly three-quarters of its population being Jewish) is completely encircled by predominately Muslim nations. Lebanon is on Israel’s north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan and the West Bank are east, Egypt south-west, and the Gaza Strip (and Mediterranean Sea) to the direct west.

In addition, while they do not share a border with Israel, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey are all countries in the region which have predominantly Muslim populations . Thus, if one posed Jesus’ question to those living in Israel today, the answer to “Who is my neighbor?” would be “Muslims”—almost exclusively Muslims.

Now, to be clear, none of this is to imply that the Jewish people are somehow in danger simply because their neighbors are predominately practitioners of Islam. However, since 16 of the 18 countries typically considered part of the Middle East are largely inhabited by Muslims, and since Judaism and Islam have both typically taught that the “Holy Land” is God’s gift to their specific people, one can see how this scenario could be tense at times.

Regardless of how “nice” you are or how “loving” you try to be, if your theology states that God has gifted you something, and if you have reason to believe that someone other than you has possession of that God-given gift—or that someone is threatening to take away that which God has given you—then it seems obvious why there might be some tension manifest by those who feel slighted on this point.

The theological teaching that the descendants of Abraham/Ibrahim through either Isaac (for Jews) or Ismā'īl (for Muslims) have a God-given right to that land doesn’t simply increase hostilities; for some, it demands them. After all, what message does the rightful heir send to his or her God if that believer does not desire and defend the gift God has given?

But Who Was Here First?

There is a popular saying that “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” While that’s not legally true, it plays an additional role in the challenges faced by those living in or around the current State of Israel. The “Holy Land” has been in the control of (or “occupied” by) various groups at various times throughout its history, and those who ruled typically heavily controlled not just the land but also the lives of those living under their reign.

Prior to the Great Jewish Revolt (66-132 CE), the Levant was more often than not the residence of the Israelites. In some cases, they ruled it. At other times, they resided there—but under Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, or Roman rule. Nonetheless, from the early tribal period (circa 1200 BCE) through the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-135 BCE), that part of the world was considered the homeland of the Israelite people.

Christians have had their windows of control of the “Holy Land,” as well, though not to the extent that Jews and Muslims have. While Christianity had a growing presence there during and after the time of Jesus, they were nowhere near a majority population—and were not in political power. During the Byzantine Period (AD 313-638), however, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire and, consequently, their impact and presence in the land of Palestine/Israel was significant.

Additionally, during the Christian Crusades, intermittent control over the city of Jerusalem (and the surrounding areas) was had by various Christians for about 200 years. Likewise, under the British Mandate period (1917-1948), one might argue that Palestine was under “Western Christian Imperial Rule” (mostly by the League of Nations).

However, during this last phase of Christian “rule,” Arab Muslims constituted the highest percentage of the region’s residents—though the British were facilitating a significant Jewish immigration during that era.

Muslims have controlled the city of Jerusalem and the surrounding region during various stages of its history—particularly since the 7th century CE. For example, in 638 CE, they captured the city of Jerusalem from the Byzantine Empire. Muslims then controlled the land for most of the period between 638 CE and 1917 CE.

Of course, there were short interruptions to Islamic control, most notably during the Crusades (1099–1187) and during the brief Mongol incursions in the 13th century. However, even during the periods of non-Muslim rule, most of the population of the “Holy Land” remained predominantly Muslim until the early 20th century. Thus, for the 400 years leading up to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Jerusalem was essentially an Islamic territory.

While the reasons for the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel are complex and very politically, socially, and fiscally charged, a few things are worth mentioning here.

• Because of the Bible and various historical events, Jews felt an emotional, theological, and cultural tie to the land. Since much of the Western World was Christian, they too tended to look on the Levant as innately “Jewish.”

• In response to a sense of growing antisemitism in Europe (particularly in Eastern Europe), the 1897 First Zionist Congress officially launched efforts to establish a “Jewish Homeland” in Palestine.

• After World War I, the League of Nations placed Great Britain in charge of the territory of Palestine. The Brits (through the 1917 “Balfour Declaration”) indicated their support for the establishment of a “national home” for the Jewish people—and they began to facilitate migration of Jews into the region.

• Significant portions of land, which had long been in the hands of Palestinians, was now being utilized for the resettlement of immigrating Jews, which caused increasing conflicts between Palestinian Arabs and Israelite settlers. Great Britain not only struggled to maintain the peace, but many of their actions also added fuel to the fire.

• The millions of Jews slain during the Nazi Holocaust (1941–1945) generated significant international sympathy for the Jewish people and caused many to feel that Jewish statehood was really a moral imperative, rather than just a “worthy consideration” (as it had been viewed for some time).

• In 1947, the United Nations proposed dividing Palestine into two separate states, one for Jews and one for Arabs—with the city of Jerusalem under international control. However attractive this proposal was to Jewish settlers in the region, it was not an acceptable solution to those whose ancestry in the Levant went back hundreds of years. This ultimately led to a civil war in the region.

• Britain ended its mandate (or control over the region) on May 14, 1948. The Brits withdrew, and the State of Israel was officially founded. Though this immediately led to the Arab-Israeli War (1948-1949).

•In the years since the State’s official establishment, a series of controversial expansions into formally Muslim lands have taken place. Many of the expansions were the result of regional wars. However, others—such as Israeli bulldozers demolishing Palestinian houses in the Mughrabi Quarter in order to expand the Western Wall Plaza—were much harder to justify than defeating one’s perceived enemy in an armed conflict. Each of these expansions, regardless of their form, has added to the challenges in the region.

Clearly, many factors have played into the establishment of the founding of the State of Israel. However, as the list above suggests, the manner in which many of these events unfolded has increased tensions in the region and have made civilians (who were not responsible for the decisions) the victims of the process and its fallout.

Summary of the Challenge

Regardless of which side you’re inclined to take, this is hardly a simple issue. Conflicts are inevitable, and that’s as true in the Levant as it is anywhere else in the world. However, you have a recipe for disaster when you add (to the normal challenges brought about by human nature) the following factors:

- The historical fact that the Israelites were a constantly displaced people.

- The intensely sacred nature of the region for multiple religions.

- Scriptural precedent in more than one religion for ownership of the land.

- Historical precedent for more than one group residing there when the other arrived.

- A group feeling “surrounded” by massive numbers of perceived enemies.

- Expansion of a perceived enemy into the territory of another group.

- International sympathies spawned by horrific atrocities to an ethnic minority.

- Complete outsiders (like the UN) deciding the fate of a land and people not their own.

- Manifest nationalism by multiple groups.

- Deep and ongoing suspicions manifest by both parties toward each other.

- An imbalance of power and politics in a given local.

As a result of these, and numerous other factors, there is the perception of never-ending war in the region. And yet, can we say with accuracy that “Israel is always at war with its neighbors”?

Doing so might strip all of this of its historical context. There is zero question that there has been conflict in this region from the very first days of human existence (according to the Qur’an and the Bible). However, that conflict began before the “Israelites” existed as a people, and the State of Israel today is not the same entity as the “Israelites” of ancient Jacob’s day—even if one can make the argument that one group descended from the other.

The point is, the region has seen never-ending conflict, but associating that with a singular people (i.e., the State of Israel or the Jewish people) leaves out the evolution of the territory, its residents, who has ruled, and even who has “occupied.”

Thus, rather than asking “Why is Israel always at war with its neighbors?” it might be more accurate to ask, “Why has nation after nation fought to own or control that part of the world?”

We need to remember that, in addition to the Israelites, there have been others—the Canaanites, Philistines, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Christians, Muslims, and even the League of Nations—who have conquered, occupied, or controlled that site so sacred to Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Are the conflicts in the region the result of one people or one nation?

Taken in the aggregate, definitely not!

Are current conflicts primarily the consequence of the choices of one group of people? Only if you strip those conflicts of thousands of years of history and belief.

So, yes, the Levant is an embattled land, and innocent people have suffered as a result—and continue to suffer as a consequence.

While the land of Palestine has a culturally and theologically rich heritage, it also has a horrific history that goes back thousands of years. One might argue that the State of Israel (today) has seemingly unending conflict with its “neighbors.” Nonetheless, to be accurate, one has to consider the many factors listed above when seeking to understand what’s really behind the challenges in the region. In doing so, one may still point the finger of blame; but an accurate reading of the events leads us to the conclusion that the challenges in the “Holy Land” are not the result of one people, one nation, one religion, or one era. Rather, they have existed for millennia and for myriad reasons; and even those who engage in the conflicts often don’t themselves know the full reason behind their seemingly eternal struggle.

Additional Reading:

A Brief History Of Israel And Its Conflicts

Israel Strikes Iran’s Nuclear Sites: A Moral Analysis

The 100 Most Holy Places on Earth

Library of World Religions

6/27/2025 2:48:21 AM