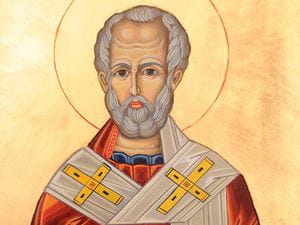

St. Irenaeus, Oldest and Newest Doctor of the Church

Later this year, Pope Francis will officially add St. Irenaeus to the roster of doctors of the Church. Why now, after 2000 years, does a pope ask Christians to turn their eyes to a man whose extant works are difficult for even graduate students? The original Greek doctors – Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianzen, and Basil the Great – and the first four Latin doctors – Augustine, Ambrose, Jerome, and Gregory the Great – offer the 21st century Christian enough treatises, commentaries, and homilies for years of spiritual reading. The official number of doctors has roughly doubled since 1870. Why elevate yet another ancient?

Designating an already-canonized saint as a doctor is not really about conferring honors, but is rather a teaching tool. What does the Church need to learn today that Irenaeus can teach us?

In the second century, defended the tradition handed on to him from the apostle John through John’s disciple Polycarp. He battled against what Benedict XVI has described as an “elitist and intellectualist” version of Christianity. In a different sort of conflict, he led the Christians of Lyon through persecution and was rewarded with a martyr’s death.

His most well-known work is Against Heresies. A title like that seems not to match his name, which contains a Greek word for peace, much less Francis’ intended title for him, Doctor of Unity. And yet, what peace or unity is to be found in the proliferation or toleration of false teaching?

In his remarks about Irenaeus, Pope Francis indicated that Catholics and Orthodox already find themselves in harmony regarding this ancient theologian. The official designation of Irenaeus as a doctor walks the Roman Church one step closer to the East. Many Christians have resigned themselves to division, and few list the reunion of all Christians as an achievable priority or even desirable goal. For Irenaeus, in contrast, only unity of belief and of communion made any sense at all. Fracture was a sign of falsehood, and heresy the product of a lack of virtues such as charity and humility. For this doctor, the accuracy of truth claims – in particular, about the Incarnation, the goodness of creation, and God’s desire to make salvation known to all – was everything. His faith rested on the reliable handing-down that was so obvious in his own life.

The word for this ecclesial principle is apostolicity, without which there is no rule of faith. As Irenaeus wrote:

The Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered throughout the whole world, yet, as if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth.

For further conversation on this topic, see this piece by Patheos author William Hemsworth. For a complete text of Against Heresies, go here. For more thoughts about the reunion of Orthodox and Catholics, read this.

Doctoral Candidates

As individuals and as a body, the Church always stands in need of reform. Some of the best reformers are deceased. Shall we cease to heed their teachings, letting them fade from memory? In addition to Irenaeus, what other saints might a pope or council bring forward as a doctors given the needs of our day?

Here are four saints eligible for future ‘doctorates,’ some of whom are already under official consideration.

1. Mother Teresa (died 1997/canonized 2016)

Mother Teresa put into writing what most people heavily engaged in direct service have not had the time or skill to do: write about it. Along with her speeches and interviews, her writings make differences between liturgy and service seem merely incidental; the Christian life is one of “Seeing and adoring the presence of Jesus, especially in the lowly appearance of bread, and in the distressing disguise of the poor.” Her journals illuminate a way to move forward when one’s path leads through a spiritual desert of doubt.

But why should the pope bother to promote someone who is already so well known? One reason is the shortness of cultural memory. Gen Z never met her, so for them she is just one of the thousands of holy people who might or might not be relevant to them. Making her a doctor would push them and future generations to grapple with her beautiful and startling ways of talking about the Christian life.

2. Josemaría Escrivá (1975/2002)

Escrivá earned two doctorates while on earth. The case for a third does not rest with his impressive university scholarship, but with the homilies and writings he created for Opus Dei, the movement he founded. Opus Dei proclaims that every single person is called to be a saint, and that one does not need to depart for a distant mountaintop or look for a dragon to slay in order to succeed. Holiness is available even – perhaps especially – in routine: “The tying of one’s life to a schedule, to a timetable, you tell me, is so monotonous! And I answer: there is monotony because there is not Love.”

He lived in the cluttered 20th century, in which swaths of people found themselves drowning in possessions and choices. His counsel for his contemporaries: “Anything that does not lead you to God is a hindrance. Root it out and throw it far from you.”

3. John Henry Newman (1890/2019)

Even Prince Charles, an Anglican, has recognized the worth of this Anglican-turned-Roman Catholic priest. Father Ian Ker, the world’s leading authority on Newman, has compared him to the Church Fathers and to St. Bernard. Newman’s scholarly attention to the patristic and scriptural sources resulted in his ability to bring forward ideas – about the laity, conscience, and development of doctrine, to name but a few – without which it would be difficult to imagine our contemporary Catholicism.

But Newman did not simply re-present treasures of the theological tradition; he gave them synthesis and a home in a modern context. The case for Newman’s designation as Doctor was made ably seventy years ago by German theologian Erich Przywara, who wrote “that there blows a breath in Newman’s theology so great and overpowering that it fills and completes even the widest cracks in Augustine.”

4. Ignatius of Loyola (1556/1622)

Ignatius is one of the major teachers of the people of God. His doctrinally insightful writings are deep, reliable, useful, and perhaps more widely read than any other candidate’s over the last half millennium. The holy zeal of St. Ignatius stands out in the communion of all saints even as it did during his life.

Perhaps popes have never made magisterial recognition of Ignatius’ enormous influence a priority because it seems unnecessary. On the other hand, perhaps hesitation to encourage the worst (both de facto and de imaginatione) of the Jesuit Order Ignatius founded has deterred past popes from bringing his name forward. If ever there was a pope who might, it would probably be the current one, a spiritual descendant of Ignatius himself.

Dead Poets Society

By little-t-tradition, martyred saints have not been designated as doctors; Irenaeus, martyred in Lyon in a wave of anti-Christian persecution, will be the first. Two 20th-century martyrs deserve similar consideration. Strangely, the designation of ‘martyr’ itself proved controversial for both of them. Both wrote like poets and died at the hands of murderous militaries; their lives and their writings testify to a faith that does not limit itself to a sanctuary but pervades all aspects of life.

5. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, née Edith Stein (1942/1998)

Teresa Benedicta was a German Jew who read herself into Christianity and became a Carmelite nun before being hunted and killed by the Nazis. Her writings have enriched the corpus of mystical literature , but she is perhaps more notable for her heady contributions to the integration of serious philosophy into the discourse of faith. She wrote these lines about the Eucharist:

Your body mysteriously permeates mine

And your soul unites with mine:

I am no longer what once I was.

6. Oscar Romero (1980/2018)

Romero was an El Salvadoran shepherd in the style of 12th-century Thomas Becket of Canterbury. He does not fit neatly into anyone’s political or ideological categories because, like Mother Teresa, he was focused on fully Catholic ministry to the suffering poor. In the midst of an ugly civil war short on heroes, he took care in his homilies and radio addresses to shine the light of the gospel on violence and greed on all sides. Romero directly begged soldiers and guerillas to put loyalty to Christ first and be ready to defy unjust orders: “No soldier is obliged to obey an order that goes against the law of God!” He was gunned down by an assassin while celebrating Mass. His death as a martyr underlined rather than defined his holiness.

Romero’s writings, homilies, and broadcasts reveal a man thoroughly awake to grace and more than willing to give up everything for Christ. Pope Francis wore Romero’s bloodstained liturgical belt at his canonization ceremony in 2018.

Referrals from Dr. Google

University professors are evaluated by their deans based on whether any students enrolled in and showed up for their classes. This market-based valuation is not really fair, for students often act like swine before pearls. It might be fairer to judge the other way around, evaluating the students by what professors they select and what courses they actually attend.

In the same vein, Christians might be judged on what teachers we trust and whether we read more than the backs of their books. Just as Irenaeus relied on Polycarp to hand on the faith to him, and Polycarp upon John, and John upon the Word Incarnate, so we rely on a great chain of witnesses. Very fortunately, those witnesses have online office hours for personal tutoring, as most of their writings are available for free as pdf files. Query any doctor of the church and follow the threads. Seek and ye shall find.

1/21/2022 7:14:15 PM