Critics have been lukewarm towards Lewis Capaldi’s latest endeavor, Broken by Desire to Be Heavenly Sent, released only last month. Reviews to date have given his album tepid scores, from the middling to the slightly-better-than-average: a solid six out of ten seems to be the consensus.

For young Lewis – the Millennials’ answer to Susan Boyle, another winsome Lowlander whose voice put its owner on the metaphorical ScotRail express from obscurity to stardom – that reception will disappoint.

As a charitable soul, I thought our man Capaldi deserved a more generous response. Then again, commentators never deign to lavish too much praise on a popular artist. It’s better for their brand, apparently, to play the highbrow maverick exposing how shallow those of us plebs are who like him.

For this reason, I handle the negative reviews with an ample pinch of salt – preferably the peri-peri sort you get on your chips at a Nando’s chain, all the better to chase the taste of online cultural snobbery.

Not every release has to be revolutionary. Capaldi’s twelve new songs may share the same structural outline (verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus) and other features besides, but who really cares? It works. Any time I hear something by Lewis Capaldi, the words of Reverend Seaton from BBC Three’s This Country spring to mind: ‘It certainly feels like it has a winning formula.’

Yes, Broken by Desire is good. Even I, however, have reservations about certain songs. The chorus in “The Pretender” gave off low-key Disney villain vibes for me; with lyrics like ‘designed to deceive,’ I half-expected Melissa McCarthy’s Ursula from this year’s Little Mermaid remake to guest-appear in the music video.

“How This Ends” is, like the grey linoleum in a hospital cardiology room, tough to have any burning opinions about. It sticks to the [K]apaldi Patty Secret Formula – studiously generic yet undeniably satisfying, as is the food in a certain restaurant under the sea. That’s about all I can say.

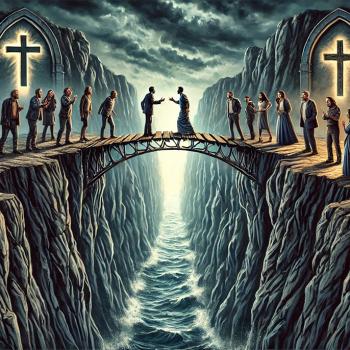

Now to the positive side of the ledger. “Heavenly Kind of State of Mind” is typical of other items in this album’s first half as a boppy feelgood song. (À la Shaun of the Dead, things take a darker turn for the final act.) We find in it abundant religious imagery; that means the track is fair game for a Patheos article!

With all this Christianese and a zippy melody to boot, I could foresee “Heavenly Kind of State of Mind” entered in the next edition of Junior Praise. Well, maybe minus the naughty line, ‘I could tell the devil to go fuck himself.’ Better stick with, ‘Get thee behind me, Satan,’ I think.

Essentially, Capaldi draws on biblicisms to convey the revived self-confidence which comes from a healthy relationship, hence those choice words he has for the Prince of Darkness. The Bible also donates a full vocabulary for expressing attraction, from the lover’s looks which make their beholder ‘feel the rapture’ to their voice ‘like a chorus only angels can sing.’ Clearly, this person is a keeper!

Every song should have a central conceit or through-line to make it coherent. Since all the metaphors in this track originate from Christian doctrine – without ever feeling trite, I should add – they mesh together well. Tossing in images that aren’t faith-based would rupture the religious theme. ‘You call me like a chorus only sirens can sing,’ a reference to Greek mythology, wouldn’t work for that reason.

Christian scripture contains a wealth of individual beliefs, all of them available to the song-writer for deployment as figures of speech. In “Heavenly Kind of State of Mind” – a track only 3 minutes, 22 seconds long – Capaldi mentions: blasphemy, the devil, the afterlife, heaven, salvation, original sin, angels, sacrifice and the Rapture. That’s quite a roll call but still there are plenty left over: the Trinity, the Creation, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, the forgiveness of sins…

The list goes on. Capaldi, remember, comes from Scotland, where mainstream Christian institutions are secure in their doctrinal identity. The Church of Scotland holds the lengthy Westminster Confession, a hefty document which outlines all sorts of religious tenets. The Westminster Standards cover way more ground than the Church of England’s Thirty-Nine Articles.

Another factor which accounts for why Christian tradition appears in so many pop songs has to be the continued resonance of its concepts even in an increasingly secular world. You would expect a story that enthralled hundreds of millions of imaginations over two millennia to have a decent amount of staying power.

When you listen to “Heavenly Kind of State of Mind,” you don’t need a printed fact-sheet in front of you, defining what original sin is or what angels are. If such a thing as collective consciousness exists, then the biblical mythos remains part of our knowledge in English-speaking societies. After all, makers of musical and literary culture keep reaching for it – much as painters do the primary colours – to resource their work.

Perhaps, as my final thought on the topic, the will to subvert expectations is a driving force too. Pop artists are keen to build attention-grabbing personas – often totally bonkers; remember Lady Gaga’s meat dress from 2011?

Reworking Christian dogmas (associated with stuffy services in fusty buildings) into striking images can strengthen a singer’s reputation for inventiveness, though not as much as a garment made of animal flesh does…

If I were to make a prediction, then, I’d say we will be hearing songs inspired by religion, particularly Christianity, for quite some time. Here is a sample from the beginning of 2023: “Heaven” (February, Niall Horan), “Miracle” (March, Ellie Golding feat. Calvin Harris), and “Praising You” (April, Rita Ora feat. FatboySlim). So many bangers thus far, and the year isn’t even half spent!

6/13/2023 5:11:22 PM