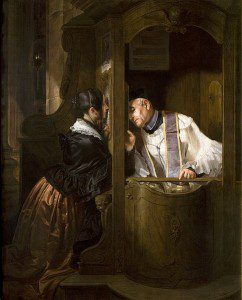

I have a confession to make.

Years ago, before I converted to Catholicism, I harbored suspicion about the Catholic Sacrament of Confession (also known as the Sacrament of Reconciliation). Now, let me be clear. As a Lutheran, I always believed in the importance of praying to God and asking for the forgiveness of my sins. That was simply “part of the Christian deal”. God created us, loves us and passionately wants a relationship with us. Unfortunately, we screwed up that relationship in the beginning and continue to screw it up. As a result, we separated ourselves from God and are dependent on his loving Grace to be reconciled to him. Yet, to achieve that reconciliation, we needed to approach him, admit our sin, demonstrate our contrition and ask for forgiveness. In sum, to heal the rift between God and us, we must repent. This seems simple enough. So why, I sniffed, do we need priests, confessionals, examinations of conscience, terms like venial and mortal sins, and the horrific penance? Is this a “power thing”? Is it an empty attempt at bureaucratization of my relationship with God? Is it an effort to impose that infamous Catholic guilt over a process that should bring release and joy?

Over many years, these self-satisfied musings kept me warm and smug in my debates with my Catholic wife. I was right, I insisted. Why couldn’t she see that? *Sigh* But time would pass and slowly, imperceptibly something changed. I began to think about how I confess my sins. And ,to be honest, here’s the bombshell: I’m not very good at it. I’m lazy. I’m imprecise. I’m rationalizing. I’m irregular.

So here is what I learned from the Catholic Church about the Sacrament of Confession.

1) We must understand WHY we need to confess:

G.K. Chesterton, the incomparable British journalist, author and Catholic apologist, helped me think anew about Confession. After his long road to Catholic conversion, Chesterton quite simply responded to the haughty opinion makers who scolded that Confession was morbid.

“The morbid thing is NOT to confess [your sins]. The morbid thing is to conceal your sins and let them eat away at your soul, which is exactly the state of most people in today’s highly civilized communities.”

To be brief, we need Confession to be made whole again.

—————–

2) We must understand WHAT we are confessing:

When I first encountered the Examination of Conscience, I was shocked. I realized what an amateur I was at seriously and honestly considering my sin. For years, I would perform a cursory survey of my actions over the recent days and then ask God to forgive me. However, the effort was half-hearted because my sins were conveniently vague and increasingly lost in the ether of time and lazy memory. The Examination of Conscience based on the Ten Commandments, the Beatitudes or Catholic Social Teaching seriously called me to account with pointed questions that closed loopholes, illuminated dark corners and rebutted my best excuses. The distinction between mortal and venial sins helped me to consider the depths of offense to God and the gravity with which I must choose aright in my daily decisions. And to confess to a priest asked me to be accountable, to be precise and to be prepared for words of much-needed correction along with words of absolution. The key, I have learned, is that we all need to be brutally honest about our sin so that we can empty ourselves, be open to God’s Grace and strive to correct our future course with God’s deep and abiding mercy.

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the wisdom that the elder monk, Zosima, would impart to two supplicants speaks eloquently to the spirit necessary for the Examination of Conscience prior to the Sacrament of Confession,

“Above all, stop lying…The important thing is to stop lying to yourself. A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies, becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else, and he ends up losing respect for himself as well as for others.”

—————–

3) We must understand HOW we are changed by confessing.

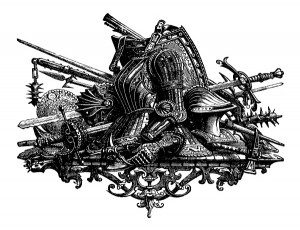

In the Robert Bolt’s play (and subsequent movie), The Mission, Rodrigo Mendozo (played by Robert De Niro) is a malicious slave-trader and mercenary who finds himself in the blackest depression. Having spent his life ruthlessly kidnapping and enslaving South American native tribesmen and ultimately killing his half-brother in a jealousy-inspired duel, Mendozo confesses his sin to a Jesuit priest/missionary, Fr. Gabriel. Fr. Gabriel encourages Mendozo to adopt an appropriate penance. In one of the most stirring scenes from the film, Mendozo has wrapped himself with coarse, thick rope enabling him to drag a netted mass of swords and armor – the very instruments of his sin – through the unforgiving South American jungle. Bloodied, exhausted and emotionally broken after brutal jungle distances, Mendozo collapses and weeps with bitterness. But his bitter tears soon give way to joy as the very natives he had hunted so viciously cut his rope off and shower him with incomprehensible kindness and mercy. A grace of sorts, if you will.

By naming our sin, but moreover recognizing the bitter offense it has inflicted upon our all-loving Father and our neighbors, we must honestly grapple with the gravity of our act and hunger – yearn – to make amends. By confessing our sins, we empty ourselves of darkness and open ourselves to light. God’s Grace absolves us. But our penance is our insufficient, but mindful attempt to honor this absolution and hold fast to a lesson that hopefully will correct our future ways.

—————–

4) We must be GRATEFUL for what confessing brings us.

In the 1930s and 40s, Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer courageously defied Adolf Hitler and the wickedness of National Socialism. At the root of his rebellion was his Christian Faith. While Bonhoeffer would die a martyr in a concentration camp, it was not without imparting deep wisdom to those hungering for truth. We are saved not by our own efforts, he reminded us, but by God’s magnificent Grace manifested by his bloody death on a cross. And while we cannot earn Grace, we can live a life spirited by unending gratitude for a debt we can never repay. Honest Confession embraces and lives in awe of “costly grace”. We should beware, Bonhoeffer warned, the siren song of “cheap grace”.

“Cheap grace is the grace we bestow on ourselves. Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession…Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.”

Why should I go to Confession? What, truly, are my sins? How will Confession change me? How can I show my thanks? Well, what do you know? I guess the Catholic Church offered good answers to these questions after all…

Now, if you’ll excuse me.

I have a Confession to make.