I am working my way through Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honor trilogy.

And it is fantastic.

The novels which comprise the trilogy (Men At Arms, Officers and Gentlemen, and Unconditional Surrender) take us through the irony and tragedy of the Second World War as seen through the eyes of an aging British soldier, Guy Crouchback. As is classic for Waugh, the story has countless moments of the subtlest wit which shine a bright light on the stories we tell ourselves juxtaposed against the realities we actually live. And though puckish to the point that might be considered a touch cruel, Waugh can stagger with moments of deepest poignancy. This is what I found in Guy Crouchback’s father.

Guy Crouchback is an British expatriate returning home to enlist in the British army in order to fight against the scourge of National Socialism. What he finds upon returning to England is surreal. Ill-equipped and ill-prepared for the war that has come upon British society, the fundamental questions of aims and intentions in the impending conflict seem strangely unanswered. And though his attitudes towards service and patriotism, justice and honor seem practical to Guy, they were considered oddly out-of-step by all around him.

Except for his father.

And though there is still so much for me to discover about Mr. Crouchback, it was my introduction to him in Men at Arms that amazed me. My first exposure led me to reason that Mr. Crouchback is Evelyn Waugh’s perfect father. Why? Two simple reasons.

He was content.

Mr. Crouchback was a widower who had seen his family estate and fortunes dwindle. But in the sweetest of fashions, he simultaneously maintained a rich devotion to his family’s honor-worthy name while bearing no resentment or embarrassment about its losses. Waugh would write,

“He was not at all what is called ‘a character’. He was an innocent, affable old man who had somehow preserved his good humor – much more than that, a mysterious and tranquil joy – throughout a life which to all outward observation had been overloaded with misfortune. He had like many another been born in full sunlight and lived to see night fall.”

“He had an ancient name which was now little regarded and threatened with extinction. Only God and Guy knew the massive and singular quality of Mr. Crouchback’s family pride. He kept it to himself. That passion, which is often so thorny a growth, bore nothing save roses for Mr. Crouchback.”

“He had a further natural advantage over Guy; he was fortified by a memory which kept only the good things and rejected the ill. Despite his sorrows, he had had a fair share of joys and these were ever fresh and accessible in Mr. Crouchback’s mind. He never mourned the loss of [his estate]. He inhabited it as he had known it in bright boyhood and in early, requited love.

In his actual leaving home there had been no complaining. He attended every day of the sale seated in the marquee on the auctioneer’s platform, munching pheasant sandwiches, drinking port from a flask and watching the bidding with tireless interest, all unlike the ruined squire of Victorian iconography.

‘…Who’d have thought those old vases worth 8 pounds?…Where did that table come from? Never saw it before in my life…Awful shabby the carpets look when you get them out…What on earth can Mrs. Chadwick want with a stuffed bear?’ [he would wonder]”

He was faithful.

“Once a year he revisited [his estate], when a requiem was sung for his ancestors. He never lamented his changed state or mentioned it to newcomers. He went to mass every day, walking punctually down the High Street before the shops were open; walking punctually back as the shutters were coming down, with a word of greeting for everyone he passed. All his pride of family was a schoolboy hobby compared with his religious faith.”

And when Mr. Crouchback discussed the inestimable value of the faith symbolized by the medal of Our Lady with his son Guy – the medal worn by Mr. Crouchback’s son Gervase who had been killed in the First World War, Guy responded,

Guy Crouchback: “It didn’t protect Gervase much, did it?”

Mr. Crouchback: “Oh yes, much more than you might think. He told me when he came to say goodbye before going out. The army is full of temptations for a boy. Once in London, when he was in training, he got rather drunk with some of his regiment and in the end he found himself left alone with a girl they’d picked up somewhere. She began to fool about and pulled of his tie and then she found the medal and all of a sudden they both sobered down and she began talking about the convent where she’d been at school and so they parted friends and no harm done. I call that being protected. I’ve worn a medal all my life. Do you?”

Guy Crouchback: “I have from time to time. I haven’t one at the moment.”

Mr. Crouchback: “You should, you know, with bombs and things about. If you get hit and taken to a hospital, they know you’re a Catholic and send for a priest. A nurse once told me that. Would you care to have Gervase’s medal…?”

Guy Crouchback: “Very much…”

Now these are just the introductory moments with Mr. Crouchback. But I was stunned. For it is clear that this man had gone through loss. Deep loss. It is clear that he lived in an age of aristocracy, an age of uncertainty, an age of imperfection. And yet it is very clear that in spite of it all, Mr. Crouchback found himself content and faithful. Not only had he honorably endured his hardships; he had become better in the face of them. And as the story unfolds, this character of contentment and faithfulness impacts his son. And it deeply impacted me.

Why?

Because, imperfectly, that is what I am striving to be: content and be faithful.

In his utter simplicity, Evelyn Waugh’s father is an extraordinary model.

Content. Faithful.

Perfect.

—————————

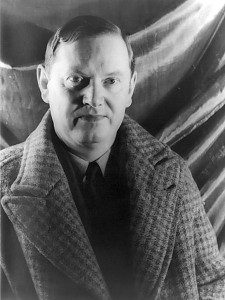

Image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Waugh#/media/File:Evelynwaugh.jpeg