It was the day before Thanksgiving 27 years ago and I was the only reporter at The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel without family in western Colorado, so I got the airport assignment.

“Go to Walker Field and find a coming-home story, people hugging at the airport,” the city editor told me. “Bring Brad (the photographer), he’ll know what to do.”

“Right,” I said. “The spirit of Thanksgiving.”

Twenty minutes later Brad and I were sitting in the terminal at Walker Field Airport, snacking on Fritos and sharing a root beer along with dark remarks on whether anything remotely interesting woud happen. A 707 emerged from the sky over the Grand Mesa, landed smoothly and taxied to the terminal in the gathering dusk.

Meeting Black Elk

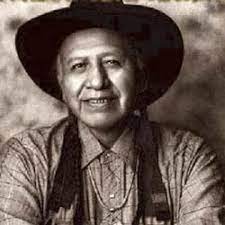

Clumps of people walked through the sliding doors, Brad took a picture of a little kid running to hug someone and a few seconds later there he was, an older Native American man with his hair in two long black braids walking slowly with a middle-aged Caucasian woman.

“You gotta be kidding,” said Brad.

“A real Thanksgiving story,” I said, dreading the inevitable irony of the encounter. Time slowed down. I couldn’t just let them walk by, could I? The next few seconds were in super-slow-mo as the unusual pair grew closer. I had a job to do, but …

Did it have to be on Thanksgiving? I grew up in the People’s Republic of Cambridge, Massachusetts, I knew about the dark side of the desperately sick and starving Puritans, who stole corn from a Native American stash in Truro back in November 1620. I’d even been to Corn Hill. The next winter 52 Puritans died in Plymouth, or about half the congregation. Happy Thanksgiving! Then there’s King Philip’s War …

Finally the moment came.

“My name is Ben Gagnon and I work for the Sentinel, the local newspaper, this is Brad.” Everybody shook hands. He was Wallace Black Elk, she was Barbara.

“I have an assignment to talk to people who are coming home to Grand Junction for Thanksgiving and I’m sure you’re busy and everything and I can see that you’re uh, Native American, and uh, maybe there’s mixed feelings about the holiday but I was wondering if maybe you’re visiting family – I know that sounds kind of intrusive, but are you, um, celebrating Thanksgiving?”

As I reached the end of the interminable question I realized it was perhaps the longest one I’d ever asked, professionally or personally.

“I’m coming to see an old friend,” he said with a smile. “Yes, I know about Thanksgiving and I believe in giving thanks to my friends and family every day and askin’ for help and health.”

He started walking away, but I felt like this wasn’t enough for a story so I nimbly tagged along and asked him something like what his favorite food was at this time of year and I was so sorry to bother him. Being a kind person, he stopped walking and turned around.

“I’m also here for a sweat lodge this weekend,” he said. “Would you like to come?”

“Yes,” I said. “Thank you.”

“Barbara can you give him the flyer?”

I took the flyer and thanked them both again as they escaped toward the escalator. I’d never been to a sweat lodge, but that’s pretty much what a fella from the East Coast comes out West for so I holstered my pen, breathed deeply and let out a sigh that turned into a burp. The damn root beer.

“Not bad,” said Brad.

Heading to the mountains

The flyer described the Stone People Lodge Ceremony in Old Snowmass, about 10 miles west of Aspen – a two-hour drive and 2,300-foot climb in altitude from Grand Junction. The gathering was on a 957-acre property bought for conservation by John Denver and the Windstar Foundation in the late 1970s.

A short and forgettable Thanksgiving feature appeared in the Daily Sentinel with a photo at the bottom of the front page. The Internet was just revving up in 1995 and there was a lot Black Elk didn’t mention at the airport.

For example he was present at the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973, was instrumental in the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978, served as the Native American representative to the United Nations and was co-author of Black Elk: The Sacred Ways of a Lakota (1990, HarperOne).

It wasn’t until years later that I discovered he was spiritually mentored by Nicholas Black Elk, who survived Wounded Knee in 1890 and was the subject of John Neihardt’s Black Elk Speaks (1932, William Morrow & Company). The book initially flopped but after a 1961 reprint it was a counter-cultural bestseller. They practically gave out used copies on the street-corner in Cambridge and reading the book as a teenager in the mid-1970s made the requisite profound impression on me.

Getting ready

A week after the encounter at the airport about a dozen people who obviously knew what they were doing gathered to build the sweat lodge with blankets and tarps layered over tree branches and vines as a big fire heated the ceremonial rocks.

It was a sunny afternoon in late November and with reporter’s notebook in hand I asked Black Elk some basic questions about Lakota beliefs as he oversaw the work. He said the Lakota call the sun Umpawee, meaning man and woman, always together, always giving life.

“There is a force behind the flaming ball, there is fire, there is heat, then there is wind, there is sound and the sound shapes and forms life. We sit on grandmother’s lap, and she puts enough food on the table to feed everyone. The green is our carpet and our food. The ceiling is the stars and the moon is our night lamp.”

He was quiet for a little while. At the tender age of 30, I was sitting with a 74-year-old man looking over a beautiful landscape. Perhaps regretting the airport questioning, this time I didn’t say a word.

“Sometimes I feel like the trees are dyin’, everybody’s dyin’ and I’m gonna kick the bucket. Then a little wind comes, just a little bitty gust and I smell pine. And another wind comes and I smell cedar and I get stronger inside.”

In the pitch black

Inside the sweat lodge it was pitch black and the smell of cedar mixed with waves of steam as Black Elk sprinkled water over hot stones in the center of a dozen cross-legged people. I figured my shorthand would work in the dark if I really needed to write something down.

I needn’t have worried. The power of Black Elk’s personality, his delivery, the fact that it was pitch dark and the words he spoke made it the most memorable speech I’d ever heard. It was easy afterwards to work from a few scribbled notes. Black Elk described a sweat lodge “when I was a little kid” in 1943, when the spirits came to visit.

“The fish people came in there and they wanted to know how well trained we were to handle the power. We said we were only here for health and happiness and then a sound came from the mountain – WHOOM – and a big wave went over the lodge. A cold slippery spirit hit me on the forehead and on my chest and on my legs and every time one of us was hit with this cold slippery spirit, we said ‘ooh-wee!’ in surprise.

“There was a warbling, a chirping and a whistling from inside the rocks and I heard a voice from inside the rocks and the voice said, ‘We are fish people come here to tell you two-leggeds on the surface that they have taken the atom and dumped poison in the rivers and the lakes and the oceans and it will affect us fish people and it will affect the food and it will surface to the air and go all the way around the Earth, affecting the winged people and the four-leggeds and the two-leggeds.

“That was the first time I experienced something secret and sacred. The bomb had come from the fire of the sun and we had abused the fire, the rock, the water and the green. We are pitiful people and we have a lot to learn. We have to help one another.

“People have been terrorizin’ each other for long enough and we haven’t gotten anywhere. We have to help one another. This lodge is for health and help. Our grandmother and grandfather are waitin’ for us dirty little kids, waitin’ with open arms.”

Black Elk asked everyone to make a spoken prayer of thanks or help, smoke the tobacco pipe around the circle and send the prayers to the thunder beings. When lightning streaks the sky, he said, it answers prayers.

“The electrolytes come down and a little bitsy one falls in our head and touches our heart. Then we can touch someone else’s heart, and place a kindness in their heart.” Every one of us spoke our prayer, we all passed the pipe and I’m pretty sure each one of us meant every word we said.

A few times during the sweat lodge as Black Elk or someone else was speaking I heard a single click, softer than a lighter, maybe two rocks lightly knocking together. At the same time I saw a tiny light in the blackness. No one called attention to it. The tiny light appeared in different places. If someone was clicking rocks together they were sneaking around and using flint.

When I crawled out of the lodge, I thought we’d been inside for about 90 minutes. After standing up and regaining my sense of balance I looked at my watch, which told me it had been close to three hours. I asked Black Elk what the soft clicking sounds and tiny lights were.

“Spirits,” he said.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming in March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)