An avalanche of scholarly studies in recent decades has yielded enough evidence to make a solid case for a Neanderthal religion, complete with symbolic ritual practices held around a 175,000-year-old stone ring that may be the predecessor of the cosmic egg.

Numerous studies across Europe show that Neanderthals carefully removed wing feathers from birds, mostly golden eagles, white-tailed eagles, bearded vultures, Eurasian black vultures and ravens, according to Clive Finlayson’s The Smart Neanderthal: Bird catching, cave art, and the cognitive revolution (Oxford University Press, 2022).

With credentials in ornithology and archaeology, Finlayson makes the case that Neanderthals perceived certain birds as sacred and used their wing feathers as symbolic ornaments in rituals. He noted “a growing body of data demonstrates the appearance of modern behavior in extinct (Neanderthal) populations of Europe, well before the immigration of humans.”

Symbolic wings and talons

Neanderthals plucked the feathers of raptors at Fumane Cave in northern Italy, probably to be used as ritual ornaments in “the social and symbolic sphere …” according to a 2010 study published in the journal PNAS. Curiously, all the wing bones were gathered in a pile against the east wall of the cave.

In a similar case, Neanderthals buried only the wing bones of crows in Cova Negra cave in southeastern Spain. At the Zaskalnaya VI site in Crimea, a Neanderthal made seven equidistant notches on a raven bone about 40,000 years ago. Some archaeologists believe the cuts were made for symbolic purposes while others are unsure.

In caves from Spain to France, Italy and Croatia, archaeologists believe Neanderthals carefully removed the talons from dead birds, mostly from the rare imperial eagle. A study identified 10 sites where Neanderthals removed talons, all located in a swath of territory where two global bird migration flyways converge (East Atlantic and Mediterranean/Black Sea).

Although physical evidence is elusive, many scholars believe the talons were worn around the neck, a practice found in later indigenous cultures. In Mesoamerica, Aztec “Eagle Warriors” wore talons attached to their knees.

An anthropological study published in Science Advances in 2019 argued that if Neanderthals wore talons as ornaments, it means they “had social and cultural structures complex enough to convey the use and meaning of (the talons) both in time, from generation to generation, and through space. This represents a remarkable advance with respect to our knowledge about the symbolic behavior of the Neanderthals…”

The study added that later human cultures “have used raptor claws/talon for the elaboration of a great variety of elements associated with rituals, dances, personal adornments, grave goods, etc.”

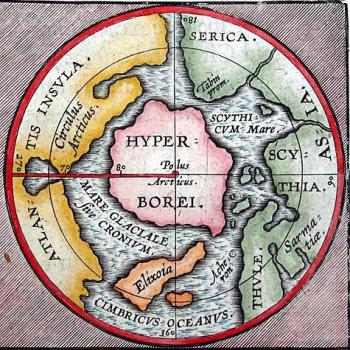

The oldest cosmic egg?

Feathers and talons weren’t the only bird-related symbolism in the Neanderthal world – there’s solid evidence that they celebrated the egg shape, possibly laying the groundwork for ancient cosmic egg mythology.

About 176,000 years ago, deep inside a cave in southern France, Neanderthals built small fires on an egg-shaped ring of stones while engaging in “some kind of symbolic or ritual behavior,” according to a recent study by a team of 18 scientists.

After navigating 1,000 feet inside a subterranean complex and inching through narrow passages, local spelunkers discovered Bruniquel Cave and its archaeological remains in 1990. The cave is located in a volcanic region known as the “Capital of Prehistory” where 15 sites make up the highest concentration of Neanderthal habitation in the world.

Reported in the May 2016 issue of Nature, the study concluded that Bruniquel Cave is the oldest known deep cave used for ritual behavior by Neanderthals, who heated and broke 124 stalagmites to create an oval ring 20 feet long and 14 feet across. Inside the oval was a circular stone ring, seven feet in diameter.

The builders lit fires on parts of the structures, where remains of burnt animal bones were found. There were no signs of extended habitation, leading to the conclusion that the cave was used “for some kind of symbolic or ritual behavior.”

Also in southern France, Neanderthals build twenty oval-shaped huts on the beach in modern-day Nice about 400,000 years ago, according to a 1960s study by the French archaeologist Henry de Lumley. Known as Terra Amata, the site yielded evidence that Neanderthals hunted red deer, wild cattle, and a small species of elephant, butchering them on the beach.

In northern Iraq, eight oval-shaped hearths made of rock crystal were found near Neanderthal burials in Shanidar Cave. Taken together with symbolic feathers and talons, it’s plausible their core beliefs included something like a cosmic egg.

In the southeast corner of the Serengeti Plain, in northern Tanzania, is the oldest structure in the archaeological record: An egg-shaped ring measuring 21 feet long and 15 feet across, with stone tools and bones inside the boundary. Located at Olduvai Gorge and estimated to be 1.9 million years old, archaeologists can’t say who built the ring or what purpose it served.

Although the measurements are nearly identical to the Neanderthal oval in Bruniquel Cave, it seems unlikely they were handed down orally over almost two million years. Perhaps in both cases the ring-makers were imitating eggs they observed in nature. The ratio of the short axis to the long axis in both cases is about 2/3, a match for eggs laid by swans, pheasants, hens, ducks and turkeys.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?

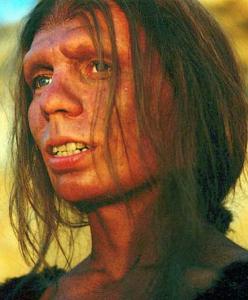

For more than 150 years western culture made a caricature of Neanderthals, depicting them as apelike, stupid and brutish. For those not keeping up with taxonomic journals, the joke’s on us.

It turns out we’re the same species, reunited by genetic science as long-lost brothers and sisters. We’re Homo sapiens sapiens and they’re Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. When geneticists examined large groups of Neanderthals and modern human they found as many differences within the groups as between them.

Plus, geneticists have confirmed in the last decade that the two subspecies interbred extensively from Europe to Asia in multiple phases and locations between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago. And that’s just what they can prove today. There’s strong evidence to support interbreeding occurred over long periods more than 100,000 years ago.

Using the delicate language of scholarship, two recent books emphasized the amount of sexual intercourse that went on between Neanderthals and humans.

“…these liaisons were not the exception but the rule, and they were essential for the rise of the often-variable and adaptable species that today we call Homo sapiens,” wrote Madeleine Boehme, author of Ancient Bones: Unearthing the Astonishing New Story of How We Became Human (Greystone Books, 2020).

“… contact and hybridizing happened a lot more often than we’ll probably ever know,” wrote Rebecca Wragg Sykes, author of Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020).

Recent discoveries at Nesher Ramla in Israel revealed a village of Neanderthal and archaic human hybrids thriving between 140,000 and 120,000 years ago. Located north of Jerusalem in a region where two global migration flyways converge, its settlers had “a distinctive combination of Neanderthal and archaic (human) features,” according to a Tel Aviv University study published in the June 2021 issue of Science.

A human portrait of Neanderthals

The avalanche of scholarship on Neanderthals in recent years continues to reveal a more human portrait that’s coming into focus despite pop culture headwinds – for more than a century the very name of our sub-species cousin has been used as an insult.

A 2017 reanalysis of bones found at Shanidar Cave in northern Iraq in 1957 found evidence of long-term care for the disabled in a male Neanderthal who had lost a forearm, gone deaf at a young age and walked with a limp yet lived into his 40s.

At sites all over Europe, the Near East and Central Asia, Neanderthals adapted to their environment by eating a wide variety of plants and animals. Neanderthal cooking was first confirmed by charred animal bones found in Israel’s Kebara Cave. It seems Neanderthals opened about 1,000 mussels over a hearth at Bajondillo rock shelter in southern Spain and roasted 20 tortoises upside down in their own shells at Cova Negra Cave.

At 15 coastal sites on the Mediterranean Neanderthals ate crabs and limpets. In the Italian Alps they ambushed 30 bears that were either hibernating or waking up in a groggy state. Pasta was also on the menu as a study found 40 percent of Neanderthals buried at Shanidar Cave in Iraq ate boiled starches.

Neanderthals made eight-foot wooden spears to kill wild horses in Germany and knew exactly how to smash bones to remove the marrow, they tanned hides, made string and cooked bark to make tar and resins.

The leg bone of a bear with five round holes corresponding to a musical scale was found in 1995 in Slovenia, suggesting Neanderthals made music. A subsequent study argued the holes were made by the teeth of a scavenging hyena.

One thing is certain: After the Neanderthal extinction, humans settled where Neanderthals had lived, continued to use bird feathers and talons in symbolic rituals and celebrated the egg shape in ovate megalithic structures around the world.

The oldest stone enclosures at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey date back 11,500 years, and measure about 33 feet on the short axis by 50 feet on the long axis, the same 2:3 ratio found in the 1.9-million-year-old stone ring at Oldupai Gorge and the 175,000-year-old stone ring at Bruniquel Cave. As noted above, the ratio 2:3 is the same found for eggs laid by swans, pheasants, hens, ducks and turkeys.

In today’s polarized world it’s humbling to realize that two sub-species of Homo sapiens with visibly different physical traits managed to live together, raise families and, apparently, lay the foundations of the nature religions.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing; now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)