Hunter-gatherers lived in extremely busy bird migration corridors in Panama 13,000 years ago and in Israel 23,000 years ago because they understood something that science only recently found to be true.

Migratory birds substantially increase floral diversity on their seasonal grounds by carrying exotic seeds over hundreds of miles. By introducing new vegetation over hundreds of thousands of years, birds gradually redefined the landscape of their seasonal homes while feeding the soil with droppings. A diversity of vegetation ultimately leads to a diversity of animals.

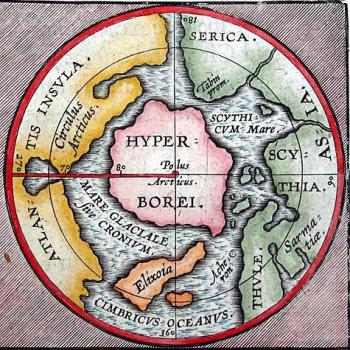

Charles Darwin had a hunch that migratory birds were responsible for delivering the seeds of vegetation around the world, but his efforts to design a reliable test were fruitless. In September 2012 and 2013, a team of scientists traveled to the Canary Islands off West Africa to pick up where the father of evolution left off.

In 2016, their study was published in The Royal Society of Biology in London, concluding that enough migratory birds carry viable seeds in their guts over hundreds of miles to be a “vector of dispersal” that contributes to the development of bio-diverse landscapes. The scientific team must have raised a glass when the study made international headlines.

The science of ancient myth

The team of scientists probably didn’t realize that ancient cultures around the world once celebrated the spring delivery of seeds to the soil by migratory birds as a sacred act of benevolence that first occurred at the time of creation.

Migratory birds follow the sun north and south every year, inspiring the belief that they were agents of the sun god, delivering the seeds of everything from rice to squash, peanuts, fruit, beans, corn, tobacco and trees, so they all might grow under the benevolent rays of the sun.

The Kaonde of Zambia say honey birds brought seeds to the first humans. In ancient Persia the Simurgh bird shook the seeds of all plants from the tree of life. In Iran divine birds took sprigs from a tree in a mountain paradise and brought them to humans for cultivation. In Northeast China magpies were said to drop the first fruits on the earth. A Jiangnan myth says sparrows stole rice from heaven.

The Algonquin told of crows bringing the first seeds to the Great Lakes region. The Hidatsa of North Dakota believed geese brought corn in the spring while ducks delivered beans and swans carried squash seeds. On the granite Tello Obelisk at the Old Temple of Chavín de Huántar, built in Central Peru almost 3,000 years ago, priests carved a raptor dropping peanuts.

Avian eco-farmers

More than 13,000 years ago hunter-gatherers burned and cleared fertile volcanic land at Lake Yeguada in Panama, about 3,000 years before the first domesticated seeds were planted in the region.

Scholars believe the burning was intended to produce a more diversified ecosystem, but this particular group of hunter-gatherers might have had something else in mind – a secret weapon of sorts.

Three of eight global bird migration flyways overlap from southeastern Mexico to Panama, producing a massive population of about 1,000 different migratory bird species. The only other regions in the Americas where three flyways converge are Alaska and Patagonia.

The purpose of intentional burning may have been to create open fields of rich, volcanic soil below a superhighway of bird migration. Considering the belief in seed-bearing birds across ancient cultures, it’s plausible that Lake La Yeguada was a sacred site attended by a priesthood of eco-farmers. Perhaps drummers, singers and dancers welcomed the waves of migratory birds arriving with seeds in early spring.

There’s also evidence of intentional burning by hunter-gatherers on the steppes of Patagonia, where human habitation dates back 14,000 years in a region where three bird flyways converge. Scholars currently believe the fires were set to flush animals for hunting, but the esoteric field of intentional burning by hunter-gatherers is not well coordinated or developed, according to a recent academic paper.

Eco-farming by the Sea of Galilee

Of the nearly 200 countries in the world, the greatest number of migratory birds (500 million) fly through Israel twice a year because it’s located at the junction of three continents. The incredible phenomenon has long attracted birders from around the globe.

The only active volcanic area of Israel includes the fertile region around the Sea of Galilee, extending southwest to Jerusalem and the Mediterranean coast. It’s a region that’s attracted human-like species for a very long time.

Homo erectus used hand axes to butcher hippos and wild cows less than two miles south of the Sea of Galilee. Neanderthals occupied half-a-dozen caves in the region over tens of thousands of years. A human-Neanderthal hybrid community dating back more than 120,000 years was recently excavated at Nesher Ramla, just north of Jerusalem.

It should come as no surprise that during the last Ice Age – about 23,000 years ago – one of the only places in the world where humans thrived was along the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee. A sprawling archaeological site known as Ohalo II includes the remains of six brush huts, open-air hearths, the grave of an adult male, thousands of animal bones in refuse piles, charred plant remains, flint tools and cereal grains.

While the hunter-gatherers on the southern shores of the Sea of Galilee enjoyed wild game and fish, there was an equal emphasis on the gathering side of the equation. Analysis of hearths, tools and plants revealed that wild wheat, barley and oats were systematically gathered, processed into flour and baked into loaves of bread. All about 10,000 years before the domestication of wheat.

In a nutshell it appears that human-like species have long gravitated to busy bird migration corridors as indicators of a bountiful ecosystem. For 99 percent of our existence humans were a migratory species defined by cross-continental treks, giving our distant ancestors the opportunity to form a strong association between high bird populations, a thriving natural environment and a greater chance to survive and thrive. Establishing settlements amid busy bird migration routes was a human trait that continued long after the advent of agriculture.

Persephone: A symbol of bird migration

Both mythic and direct evidence suggests that in ancient Greece, the link between migratory birds and the delivery of seeds in spring inspired myth-making and secret rituals held during bird migration season.

In Greek myth the young goddess Persephone is abducted to the Underworld where she eats pomegranates, a fruit that’s visibly full of seeds. Her distraught mother Demeter remains in Greece over the winter until Persephone returns in spring with pomegranate seeds. This mythic tale was not a one-off, it was celebrated every year.

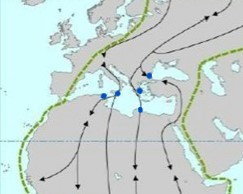

The widely shared ancient belief in seed-bearing birds encompassed ancient Greece, where a mythic dove flew an olive leaf to the Acropolis in Greece, where the leaf grew into a tree. In the more well known myth of Demeter and Persephone, it appears the latter was intended to be a symbol of migratory birds. But there’s no need to rely on speculation – at least five sanctuaries dedicated to Demeter and Persephone were built on migratory bird routes still in use today, according to BirdLife International’s bird migration maps. The shrines were always built at the highest point in the area and typically included fountains playing the role of birdbaths, a welcome attraction for migrating avians needing a rest stop. Priests likely left food for the birds or fed them directly, encouraging them to return the next year.

Shrines on bird migration routes

The oldest temple to Demeter and Persephone was built about 3,500 years ago atop a hill by the bay of Eleusis in Greece, near a north-south running bird migration route on the Mediterranean- Black Sea Flyway.

The flyway heads south from Greece across the sea to make landfall at the ancient city of Cyrene in modern-day Libya, where a temple to Demeter and Persephone was built about 2,600 years ago. Cyrene was established on a coastal plateau and was known for its fertile soil and lush plant life, helped along by untold millennia of bird droppings.

Before the mythic Seirenes became known for luring sailors astray, they were known as bird-women directed by Demeter to search for Persephone. Depicted in Greek art as the winged handmaidens of Persephone, the Seirenes failed at their task and ultimately settled on a small flowery island.

Meanwhile the Greek settlers of Szopol on the Black Sea in modern-day Bulgaria built a shrine to Demeter and Persephone about 2,500 years ago on the Cape of Stolets, a rocky outcrop near the city. Szopol is shown to be a winter ground for migratory birds on BirdLife International’s map of the Mediterranean-Black Sea Flyway.

Temples at Syracuse and Carthage

On the east coast of Sicily, the ancient civic center of the city of Syracuse was located just off the mainland on the tiny island of Ortygia, where a sanctuary complete with fountains was dedicated to Demeter and Persephone almost 2,800 years ago. Other shrines appeared around Sicily, where the cult of the goddesses was quite popular.

A route of the Mediterranean-Black Sea Flyway runs north-south along Sicily’s east coast and makes landfall by the ancient city of Carthage in North Africa, where another shrine to Demeter and Persephone was built about 400 years later.

The Carthaginian military’s “Seige of Syracuse” failed in 396 BCE, but the invaders sacked a shrine to Demeter and Persephone outside the city before retreating. After returning home the humiliated Carthaginian commander committed suicide and the plundering of the temple was interpreted as an offense to the gods, especially after Carthage was suddenly attacked by Libyan rebels.

A new temple to Demeter and Persephone was built in Carthage and consecrated with offerings intended to apologize for the plundering of the temple in Sicily.

An avian solution to the Eleusinian Mysteries?

The link between Persephone and migratory bird routes is new information in western scholarship, which has long debated the meaning behind the myth of Demeter and Persephone and the related Eleusinian Mysteries, including the annual procession from Athens to Eleusis. Some speculated that psychoactive drugs were part of the week-long festival.

Writers such as Herodotus and Pausanius wrote that the details of the Eleusisian rituals, believed to be performed mostly by women, were hidden from public view and kept secret. One thing is clear – the festival was held around the autumnal equinox, the same time of year when birds begin their fall migration.

The extended procession that ended with secret rituals in Eleusis was not unlike a pilgrimage, in this case perhaps a reenactment and celebration of avian migration that concluded with offerings to ensure success in crossing the sea.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)