The Sumerians engraved the myth of the Garden of Eden on clay tablets about 5,000 years ago to establish their cultural identity as the first farming civilization in the world. A genetic study from the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research suggests the myth is an accurate rendering of history.

The Sumerian myth begins when the vegetative gardens of the world were maintained by lesser gods under the authority of the supreme executive twin brothers Enlil and Enki, sometimes depicted with wings. One day the lesser gods said they were tired of tending the gardens of the world so Enki created humans to take over the job.

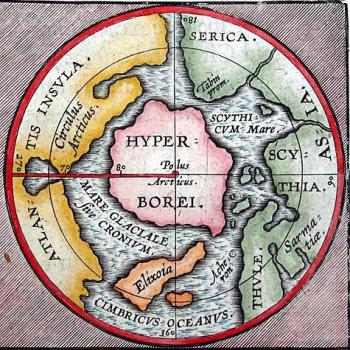

But Enlil was annoyed with the noise humans made and decided to destroy them with a flood. Having a soft spot for his creation, Enki secretly told a virtuous man to build an ark to save his family and all the animals. After the flood receded, the ark landed on a high lava plain, a basaltic landscape known in the Sumerian language as an “edin,” marking the origin of the Garden of Eden concept. Enki taught the survivors of the flood to cultivate the rich basaltic soil and grow crops.

Like many ancient flood myths the Sumerian legend reflected a fundamental shift in cultural identity – one age is wiped clean as a new one begins. In this context the Sumerian Garden of Eden was a mythic representation of the dawn of farming.

The Sumerian Garden of Eden

Scientific evidence supports the idea that farming in the Near East began in a lava field, or “edin,” specifically on the slopes of the shield volcano Karaca Dağ, which was recently identified as the original source of most domesticated plants in the Near East. The genetic ancestors of 68 contemporary cereals still grow in the wild on Karaca Dağ, according to a 2006 study by the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research. Early Sumerians were known to originate in the same region of northern Mesopotamia before establishing their civilization in the southern reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates.

Not far south of Karaca Dağ is the 11,500-year-old temple at Göbekli Tepe, the oldest megalithic complex in the archaeological record. Its thematic artwork conveys a zoo-like quality with a wide variety of animals etched in stone, suggesting it could have been a memorial to the nearby landing of the Sumerian ark with all its animals.

Not far south of Göbekli Tepe is Abu Hureyra, the oldest farming village on record, dating back 12,000 years. Perhaps Karaca Dağ was believed to be a sacred garden where early farmers gathered wild cereals to domesticate at early farming settlements nearby such as Abu Hureyra, Nevalı Çori and Çayönü. But there’smore that ties these ancient sites together.

Migration mapping evidence

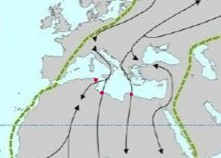

Karaca Dağ, Göbekli Tepe and Abu Hureyra are all located in a narrow corridor where the Mediterranean/Black Sea Bird Migration Flyway converges with the East Asia/East Africa Bird Migration Flyway, doubling the population and variety of migratory birds within the corridor.

The significance of a high population and wide variety of birds at Karaca Dağ, Göbekli Tepe and Abu Hureyra becomes clear in the context of a widespread, cross-cultural mythological belief that describes migratory birds delivering seeds at creation and literally shaping the landscape. The widespread nature of the seed-bearing bird myth may be due to the fact that it’s scientifically accurate, according to a 2016 study published by The Royal Society of Biology in London. The study found that migratory birds were “vectors of (seed) dispersal,” substantially diversifying the flora on their seasonal grounds. (The conclusion validated a belief expressed by none other than Charles Darwin.)

In short, it’s plausible that the busy bird migration corridor encompassing Karaca Dağ, Göbekli Tepe and Abu Hureyra was mythically embodied by the lesser gods of the Sumerians, who spread seeds to the gardens of the Near East until humans took over the job. It’s plausible that Karaca Dağ was a sacred nursery of seeds that were domesticated in nearby farming vinllages.

More evidence supporting Karaca Dağ as the original Garden of Eden is found in the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the hero travels to a jeweled garden of the gods on Mt. Mashu, where the peaks reach the heavens and the depths lead to the underworld. Described as covered in cedar trees, Mt. Mashu was said to be the source of four rivers.

Once known as Mount Masia, the volcanic Karaca Dağ towers over the landscape at 6,419 feet. Its depths have been volcanically active on and off for more than three million years. The jewels identified by Gilgamesh may have been rock crystals with large facets that naturally occur in basaltic soil, sparkling in the sun like gems.

Satellite mapping shows up to six or seven rivers running from Karaca Dağ, a condition that typically changes over time. Cedars once grew in abundance south of the Black Sea, though only a small population remains today.

Migratory birds & early farming cultures

Ancient and indigenous cultures understood that a high population of migratory birds was an indicator of fresh water, fertile soils and bountiful ecosystems. Crop farming typically began where two or three bird flyways converge, including the Fertile Crescent, northeast China, parts of North America, Mesoamerica and the Andes Mountains.

Three ancient farming cultures on the North African coast – Cyrene, Leptis Magna and Carthage – were each settled where bird migration routes make landfall as part of the Mediterranean-Black Sea Bird Migration Flyway, according to BirdLife International maps.

Legend has it that Greeks from Thera sailed to Libya to establish the city of Cyrene about 2,600 years ago on the advice of the Oracle at Delphi. About 700 miles west at a second avian landfall the city of Leptis Magna was established by the Phoenicians about 2,650 years ago. Further west the city of Carthage was settled more than 2,800 years ago. All three cities benefited greatly from soils made fertile by countless millennia of bird droppings.

In eastern Sudan the Kush Empire emerged about 2,700 years ago in a volcanic area where a major tributary enters the Nile and two bird migration flyways converge. The Kush Empire’s farming success built the opulent capital city of Meroe and more than 100 pyramids nearby.

Living in prime bird habitat

Where two bird migration flyways converge in the American West, farming began with the Hohokam in southwestern Arizona about 4,000 years ago, followed by the Anasazi and Pueblo in the Four Corners region.

Just east of St. Louis the farming hub of Cahokia developed about 1,300 years ago, again where two bird migration flyways converge. The width and breadth of the sprawling Mississippian culture matches the area where the two bird flyways overlap.

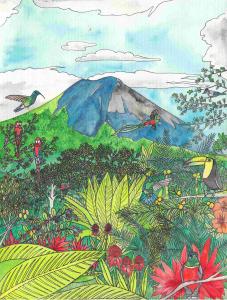

Where the rare convergence of three bird flyways occurs in southeastern Mexico and Central America, archaeologists recently discovered that Aztec and Mayan farming cultures once supported tens of millions of people.

The high-altitude farming cultures of the Andes Mountains, including the Chavin, Inca and Tiwanaku, all developed in a narrow corridor where two bird migration flyways converge, a swath of territory that encompasses sacred high-altitude sites such as the Old Temple at Chavín de Huántar, Machu Picchu, the city of Cusco and Lake Titicaca.

Cosmological seed-bearing birds

Mythological evidence across early farming cultures supports the notion that migratory birds were divine partners in agriculture believed to deliver seeds each spring. The arrival of migratory birds was conflated with spring rains, resulting in the cross-cultural mythic archetype of the Thunderbird. As the Sumerian god of springtime thunder, rainstorms and farming, the winged Ninurta threw lightning bolts, as depicted in ancient artwork.

In Chinese legend, Shennong the Flame Emperor led his people on a search for the best seed grain until a legendary Phoenix carrying grass in its beak appeared from above and dropped grain to a sunlit spot not far away. When the people ran to the spot, they found a field of tender green shoots.

The recent excavation of two mounds at Cahokia suggest that birds played a major role in sacred ceremonies. The remains of 343 swans were buried inside Mound 34 and many of the wing bones were used to make beads and awls. Cahokia is just north of a modern-day trumpeter swan wintering ground, which may have been larger and could have encompassed the city when the first mounds were built. Twenty-five bird species were found inside Mound 51, including bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, peregrine falcons, herons, pelicans, egrets, ravens, parakeets, woodpeckers and 13 kinds of ducks.

In a 2010 report on the Cahokia excavation, archaeologist Lucretia S. Kelly referred to the Hidatsa of North Dakota, who believed three species of waterfowl delivered different varieties of seed in early spring: Geese carried maize, ducks delivered beans, and swans were associated with squash. Kelly wrote that the swan burials at Cahokia were also linked to squash seeds.

Across indigenous cultures, reincarnation was not just for people. It’s plausible the ritual burial of birds, like people, was intended to be a process much like planting a seed in the soil, to bring forth a new life. After all, birds were believed to be the essential component of bountiful ecosystems.

Raptors dropping peanuts

In volcanic Mesoamerica where three bird migration flyways converge, the Aztec feathered-serpent creator god Quetzalcoatl was considered the teacher of farming and was shown carrying a pointed hollow staff filled with seeds and/or with flowers coming out of its beak.

At 10,335 feet in the Central Andes, a carving on the granite Tello Obelisk depicted a raptor dropping peanuts from the sky. The obelisk once stood in the middle of a circular plaza in front of the Old Temple at Chavín de Huántar, built 2,850 years ago where two bird migration flyways overlap.

Finally, in Greek myth, the agricultural goddess Persephone embodied a migratory bird by disappearing for six months over the winter and returning with pomegranate seeds in spring. At least five temples to Demeter and Persephone were built on bird migration routes in Greece (Eleusis), Libya (Cyrene), Sicily (Syracuse), Tunisia (Carthage) and Bulgaria (Szopol). The sanctuaries were built on the highest possible locations at coastal sites where migratory birds still take off and make landfall today, according to BirdLife International maps. (For more information see previous column.)

The Gardens of Eden

Before 2016 it was unknown to science that migratory birds distributed seeds between their seasonal grounds. Now it’s no mystery why so many large avian seasonal grounds developed into hot spots of bio-diversity such as the Yucatan Peninsula and southern Peru. The area around the ancient city of Leptis Magna is officially a hot spot of biodiversity, according to Conservation International.

Most scholars agree that bountiful ecosystems around the world inspired mythical Gardens of Eden across cultures. Improvements in bird migration mapping suggest ancient cultures chose to live in the busiest bird migration corridors they could find. These are the places that inspired early farming cultures to forge scientifically accurate stories about the role of birds in seeding the landscape, and how people ultimately took over.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)