The belief that birds guided souls through the afterlife was shared by ancient and indigenous cultures around the world for at least 9,000 years. The oldest method of soul flight was the sky burial, in which vultures devour the dead and fly their souls to the heavens.

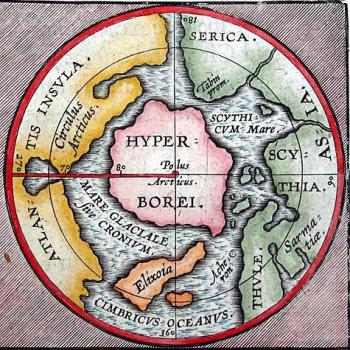

The oldest image of a sky burial appears in a 9,000-year-old mural at Çatalhöyük in eastern Turkey, showing two vultures atop a pillar with a human head between them. Most ancient cultures believed the soul resided in the head, which was likely placed on the pillar so vultures would peck out the brain/soul and carry it to the heavens.

The ancient Celts of Spain believed the souls of warriors on the battlefield went to heaven if eaten by vultures, according to an epic Roman poem by Silius Italicus. Across the globe in southern Peru, Moche artwork dating back 2,000 years shows vultures pecking at heads or body parts.

Vultures were found buried in the tombs of the elite at a Moche site and were depicted on pottery leading humans to the underworld. Meanwhile Tibetan Buddhists and Parsi Zoroastrians in the region of Mumbai, India still practice sky burials today.

But soul flight was not restricted to vultures. Throughout history a wide variety of bird species were thought to convey human souls to the afterlife.

From Egypt to Shanghai

In ancient Egypt the goddess Isis and her sister Nephthys took the form of raptors to fly to their murdered brother Osiris, finding him dismembered. Isis miraculously “originated coolness with her wings and wind with her feathers” and brought Osiris back to life, according to the “Hymn to Osiris” in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

About 2,700 years ago it became popular in Egypt to place small wooden statuettes of a human-headed bird on the chest of the mummified dead. The three-inch figures represented the ba aspect of the soul, which had the power to fly in the company of Re, the sun god. During the day the ba soul was infused with the sun’s rejuvenating energy and at night the ba flew back to the tomb and transferred the sun’s energy to the mummified corpse.

Between 5,000 and 3,100 years ago on the island of Crete, the Minoans decorated sarcophagi with birds and chariots. Early 20th century archaeologist Bernhard Schweitzer believed the Minoan birds represented an “image of the soul released from the body.”

In the Roman classic Metamorphoses, Ovid described ashes rising from King Memnon’s funeral pyre taking on the form of a bird, “which flew on whirring wings, joined in noisy flight by countless sisters born from the same source.” Eagles were often released at Roman burials.

In Norse legend, Valkyries were swan-women who carried dead warriors to Odin at Valhalla. A 6,000-year-old grave excavated in Vedbæk, Denmark, held an infant covered with the wings of a swan. At funerals for a shaman, the Yakut and Dogan of Siberia placed wooden swan effigies atop a series of poles in ascending height to represent the flight of the shaman’s soul.

In Shanghai, more than 200 “spirit jars” dominated by bird imagery have been excavated, dating to between 1,700 and 1,900 years old. There are no texts to explain the jar’s function, but Chinese scholar Kominami Ichirō believes the people depicted on the vessels are conducting a funeral service with help from the birds.

At the Senso-ji Temple in Japan the white heron dance has been performed annually for a thousand years to purify spirits as they pass from the world.

The Americas

From Canada to Mexico, the whip-poor-will was thought to locate and capture wandering souls, a notion that may have arisen from the whip-poor-will’s habit of night-flying at high speeds with its mouth wide open.

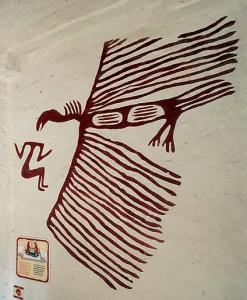

At the Native American city of Cahokia just east of St. Louis, some of the 270 people buried in Mound 72 were wrapped in beaded blankets patterned in the shape of a bird, with a bird head near the skulls. In Oconee County, South Carolina, a soapstone figurine with wings and a human head was buried in the Chauga Mound, which contained the remains of 30 people. At Spiro Mound in eastern Oklahoma, a common burial artifact was a hammered copper “Birdman” figure.

In Mesoamerica and South America, macaws, hummingbirds, and vultures were associated with burials and the afterlife. Aztec warriors and women who died in childbirth were thought to become hummingbirds in a heavenly garden.

In pre-Columbian Tlascala, east of Mexico City, the elite classes were believed to reincarnate into singing birds. In Costa Rica macaws were placed in Bri Bri burials up to the 17th century. Along the central coast of Peru, macaw feathers were braided into human hair for burials.

Birds in the global religions

The divinity of birds was a concept shared across continents and cultures, ultimately making its way into the global religions. Paintings depicting the divine conception of the Virgin Mary (The Annunciation) often depict a dove hovering in a beam that shines on Mary. In the Gospel of John, John the Baptist sees “the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it abode upon [Jesus] … And I saw, and bare record that this is the Son of God.”

A Christian legend describes a robin alighting on Jesus’ head during the crucifixion, gently removing some of the thorns and staining its own breast with blood in the process. In nature the robin enjoys feasting on the red fruits of the hawthorn tree, which have thorns up to five inches long.

Officially adopted in 325, the Christian Bible was said to be signed by the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove.

From the Qu’ran to classic Arab literature and Sufi poetry, the Islamic world has long recognized that birds have knowledge of the spirit world, which they conveyed to King Solomon and others in a secret language.

In 570, the year of Mohammed’s birth, an Abyssinian invasion threatened to overrun Mecca until the city’s defenders were joined by an enormous flock of swallows dropping small stones on the retreating Abyssinians: Mecca had been saved by the “Miracle of the Birds.” In Islamic tradition, the souls of the dead take the form of birds until Judgment Day. The soul guide in Jewish tradition is a dove.

In Ireland, jays were thought to be the souls of druids gathering acorns of the sacred oak while puffins were thought to be reincarnated monks. The widespread nature of the belief in soul-birds could once be found in County Kerry, where some believed rooks were the ghosts of cruel landlords who steal vegetables, “Always robbin’ from the poor!”

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. More information can be found at this website, which links to a YouTube video.)