Popular interest in the healing properties of rock crystals emerged as part of the 1960s counter-culture and remained a steady market until more than 50 years later when the pandemic catapulted the industry to multi-billion-dollar status.

Few realize that human fascination with crystals began at least 12,000 years ago in the Hula Valley of northern Israel where people applied plaster and calcite crystals to human skulls, then polished and buffed until they sparkled. Similar skulls were found in the modern-day West Bank, featuring cowry and bivalve shell fragments embedded in the plaster, according to Inside the Neolithic Mind by David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce (Thames & Hudson, 2005).

The use of crystals on the skulls of the dead was almost certainly intended to help the soul of the deceased navigate the spirit world. Across dozens of cultures and eons of time, shamanic figures have used crystals to see a spirit world that’s invisible to everyone else.

In Irish legend, Prince Connla was carried away to the Other World by a crystal boat piloted by a fairy maiden. He was never seen again.

Crystals once bestowed ‘second sight’

The Aboriginal shaman of Australia symbolically inserted quartz crystals into the body of his apprentice to bestow all-seeing powers – a kind of second sight that allows perception of the spirit world. The Wiradjuri of southwest Australia believed the supreme being Baiame sat on a crystal throne in the heavens, making water into crystals and dissolving crystals into water.

Before ascending on a celestial cord to reach Baiame, the Wiradjuri shaman and his student would prepare themselves by drinking water in which crystals had been immersed. When they reached the heavens Baiame sprinkled liquefied quartz on the apprentice, causing him to grow wings. Inside a crystal cave the student learned how to find souls and heal the sick.

As part of the initiation, Baiame “sings a piece of quartz crystal into (the apprentice’s) forehead so that he will have x-ray vision,” wrote Mircea Eliade in Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (1964, Princeton University Press).

The shaman of the Sea Dayaks in Borneo carried a box of quartz crystals known as “stones of light” used to find souls that wandered away from their living host and causing physical illness, according to Henry Ling Roth’s The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo (1896, Truslove and Hanson). The Semang of Malaysia believed crystals were a form of solidified water and had mystical qualities that could “see” illnesses.

The 6th century Irish abbot who later became St. Columba used a white stone from the River Ness for curing – he immersed it in water that was given to the patient. An Irishman known as McCarthy of the Glen in County Cork loaned out an oval quartz stone to farmers who steeped it in water for cattle.

Wish-granting gems

Linking gems with the ability to grant wishes was not limited to the jinn of pre-Islamic Arabia, but was also a feature of Hindu, Tibetan and Shinto gods.

When the Hindu gods churned the ocean of milk to revivify their flagging powers, numerous healing gifts were bestowed, including a physician, a cosmic cow and a gleaming gem for Vishnu.

The Tibetan prayer flag is known as the “wind-horse,” which rides among the billowing clouds, carrying the wish-granting gem of the chakravartin, radiating peace, prosperity and harmony. The Japanese muse and sea goddess Benzaiten carries a wish-granting gem while flying on the back of a friendly dragon.

Guarding treasures of gems beneath rivers, lakes and oceans from India to Southeast Asia, the Naga was half-serpent and half-human, and capable of shape shifting into full human form and marrying into royal families. The Naga guarded gems containing wisdom beyond human comprehension.

Some ancient deities were depicted with mirrors on their clothes or fastened at their joints, including the Hindu Lord Indra, the Aztec Tezcatlipoca and Tsui Goab of the Khoi tribe in the Kalahari Desert. These sky gods could see all behavior and detect all crimes. Crystals, mirrors and still water were all associated with the eye because they’re all reflective.

Cosmic crystals

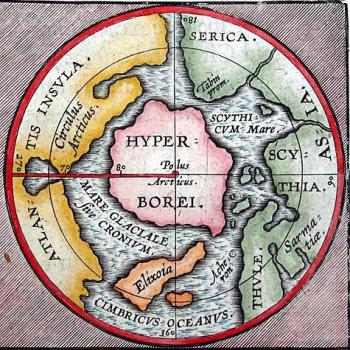

In numerous cultures the stars were equated with crystals, perhaps because they both reflect blurry tints of color. Across ancient cultures it was thought that water flowed down from the celestial pole along the Milky Way and then to earth. The cosmic waters might fall as snow on a sacred mountain and/or create sacred rivers.

Descriptions of Tur na Nog, the Irish heaven, feature singing birds perched in trees with branches of colored crystal. One legend describes nine hazel trees dropping wisdom-bearing nuts into the blazing-bright Well of Segais, from which a creator god Nechtan dipped three cups and poured out the contents to create the Milky Way and the tidal Boyne River in Ireland.

The Well of Sergais was a representation of the northern celestial pole and the wisdom-bearing nuts represented crystals. Nechtan’s daughter was Boann, a goddess of the Milky Way and the River Boyne, known as the “illuminated cow.”

In Hinduism the seat of Vishnu is in the celestial regions, from which waters flow down as braided locks in waves until the orb of the moon grows bright from the misty crystal current and falls from there to the summit of Mt. Meru. The river goddess Saraswati who carries gems, plays music on a stringed instrument and flies on a swan, was associated with the Milky Way.

Ancient Persian art shows the Zoroastrian creator god Ahura Mazda as a white-bearded man wearing a star-covered robe. Crystals, water and mist flowed down from the polar star to Lake Urvis on Mount Hugar, where it churned the waters and caused clouds to arise and bring rain all over the earth.

Recreating the heavens

The Ellora Cave complex in the State of Maharashtra, India was carved out of sheer rock over a period 1,200 years. Completed about 1,000 years ago, it was carved by Buddhists, Hindus and then Jains. A main feature is the Kailasa Temple, a representation of snowy Mt. Kailasa in the Himalayas, the home of Shiva.

The Kailasa Temple has the largest cantilevered ceiling in the world and was originally covered with white plaster intended to represent crystalline snow. Kailasa means crystal in Sanskrit. The Tibetan name for Kailasa is Gang Rin-po-che or “precious jewel of snows.”

Among the Menomini of the Great Lakes region is the following poetic legend:

When a star falls from the sky

It leaves a fiery trail.

It does not die.

Its shade goes back to its own place to shine again.

The Indians sometimes find the small stars

where they have fallen in the grass.

When we look at our reflection in still water, we see ourselves. Because the ancients regarded water as a divine and sentient entity capable of changing its form, they may have perceived the still water as seeing them.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, released April 1, 2023 by Moon Books and John Hunt Publishing. Order here or at other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, which links to a pair of YouTube videos written by the author and produced by JHP.)