About 42,000 years ago, a group of humans who had emigrated from Africa to Germany made a five-hole flute from the wing bone of a griffon vulture and left it in Hohle Fels Cave. It was discovered in 2008.

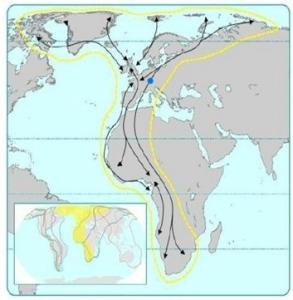

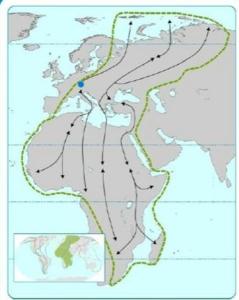

These earliest of Europeans crafted and presumably played the bird-bone flute on a major seasonal ground for migratory birds, where two global migration flyways (out of eight total) converge in southwestern Germany. The East Atlantic and Mediterranean/Black Sea flyways each carry about 300 species of birds to the area.

It’s impossible to know why the flute was made 42,000 years ago or what it was used for, but there’s cross-cultural evidence in more recent history suggesting it might have been part of a ritual performance intended to conjure an altered state of consciousness.

Supernatural birdsong

In the Gimi language of Papua, New Guinea, the word nimi translates as both bird and flute. An age-old tradition calls for men to hide in the forest and play the flute so the women and children can hear the music but can’t see the players. The intended effect is for listeners to believe they’re hearing the songs of mysterious, supernatural birds. In the rain forests of the Great Papuan Plateau, the kaluli perceive birds as spirits that communicate with the living in their songs, according to a 1982 study by anthropologist Steven Feld.

In Arizona, the Tohono O’odham once practiced singing treks to sacred sites, following the directions outlined in the verses of “The Oriole Song.” The O’odham believed their singers learned the melodies of the travel song from birds that appeared in their dreams.

A similar practice was reported among the Yoreme of northwestern Mexico, who play bird calls on a cane flute as part of ritual singing and dancing intended to transform the participants into sacred animals, including birds. In 19th century Siberia, field studies reported shamans imitating sometimes frightening bird calls such as the shrieking of raptors with keen accuracy, often using ventriloquism to throw their voice behind the audience.

The sound of the flute would have resonated and echoed inside Hohle Fels Cave 42,000 years ago, likely producing a mesmerizing effect and perhaps an altered state of consciousness. In a cave near Isturlitz in southern France, archaeologists discovered flute fragments made from the wing bones of swans between 26,000 and 32,000 years ago.

The echoing effect of flutes in a cave recalls the mind-altering music of Pink Floyd, who included bird calls in “Grantchester Meadows” from the album Ummagumma – “In the sky a bird was heard to cry / Misty morning whisperings / And gentle stirring sounds.”

Apollo: the choir conductor of swans

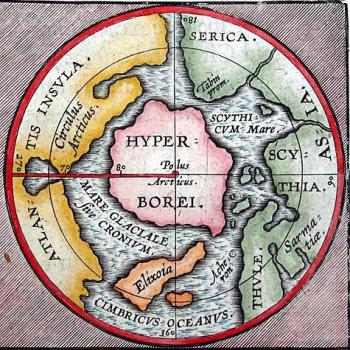

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that whooper swans and people once sang together harmoniously on a mythical island known as Hyperborea in the “far north.” He described swans circling a temple on the spring equinox as though “making a ceremonial purification of the building with their wings…”

When the human chorus sang and the musicians played, “the swans made their concordant music, not losing time or tune, as though they had got the keynote from the choir conductor, and were joining their natural music with that of the artists of the sacred minstrelsy; and then, when the hymn ends, away they fly…”

Though Siculus doesn’t directly identify the choir conductor in this passage, it’s clear the conductor is the sun god Apollo during his annual midwinter visit to his people in the far north. In Greek paintings and mosaics, swans were shown singing while men played the lyre. A medieval French bestiary praised the ability of swans to harmonize with the harp.

In Hinduism, the river goddess Saraswati embodies the flow of water, including down the Milky Way to the horizon, where it falls on Mt. Meru as crystalline snow to melt in the spring, recharging the Ganges. Saraswati was also the goddess of flowing music and was shown riding on a swan and playing the vina, similar to a lute.

The birth of the duet

In his monograph The Whooper Swan (T&A D Poyser, 2003), ornithologist Mark Brazil found the whooper to be the most vocal and intelligent of all swan species, raising young at a remarkable success rate of 85 percent. When two whoopers meet after a time apart, their greeting begins with a long duet that morphs into both birds singing the same song in perfect synchrony.

The ancient Irish admired no bird more than the whooper, which symbolized the soul and was a major player in myths centered around the swans’ winter grounds along the tidal River Boyne and the megalithic mounds in Drogheda, County Meath. It was the nightly habit of a pagan Irish king to sing half-a-quatrain to his queen, who would sing back the other half, according to Myles Dillon’s Early Irish Literature (University of Chicago Press, 1948).

The male and female laughingthrush of tropical Asia also sing duets to each other, making it possible for jazz musician David Rothenberg to improvise a duet with a laughingthrush at the National Aviary in Pittsburgh in March 2000.

Flute sounds from a hollow log

In Chinese legend, the Yellow Emperor sent his aide Linglun on a journey to find musical instruments for sacred ceremonies. Asleep in the forest, Linglun was awakened by the song of two phoenixes perched in a tree. Seeking to imitate the beautiful music, he fashioned a piece of bamboo into a musical pipe and produced the first 12-note musical scale. A 9,000-year-old flute found in Henan Province, the cradle of Chinese civilization, was reconstructed and played at a ceremony in 1999, making it the oldest playable flute in the world.

A similar legend of the Brulé Sioux tribe in Wyoming describes a young man who dreamed of a singing woodpecker and awoke the next morning to see a woodpecker singing the song in his dream. The bird flew off a little way and the young man followed until they arrived in a clearing where the hollow trunk of a dead tree lay on the ground.

The woodpecker had made regular holes up and down the length of the hollow log, and as the wind rose and blew through the hollow log, beautiful melodies emerged. The young man learned to make and play the flute and won over his sweetheart with his music. Soon all the men of the Brulé Sioux were making flutes. In the Great Lakes region, it was said that Ojibwe flute music was inspired by the call of the loon. The Shasta of central California credit the falcon with inventing the flute.

“birds instructed men … ”

Classical scholars gave birds credit for inspiring the first musicians. “The invention of music was conceived by the ancients from the sounds of birds singing in the wild,” according to the Greek Athenaeus.

In his classic On the Nature of Things, the Roman philosopher Lucretius wrote, “Thus birds instructed man, and taught them songs before their art began.” The call of the cuckoo is believed to be the earliest bird call to be incorporated in musical notation in the 13th century English “Sumer is icumen in.”

Beethoven was quoted telling a friend that he wrote “The Scene at the Brook” on one of his daily walks, with “the yellowhammers above, the quails, nightingales, and cuckoos all around, compos(ing) with me.” The nightingale’s song is featured in Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

In one of Mozart’s journals, he wrote of teaching his pet starling to sing the opening theme of a piano concerto. Mozart was so fond of the bird that he held a funeral when it died and composed “A Sextet for Strings and Two Horns” that resembled the starling’s song.

Birds & soul in rock ‘n roll

From seagulls to crows and the disco duck, birds have been used for band names and song titles for generations in modern western culture, from The Byrds to The Yardbirds, Atomic Rooster, The Partridge Family, Paul McCartney & Wings, The Eagles, A Flock of Seagulls, The Black Crowes, and Counting Crows.

Some of the most memorable rock ‘n roll songs invoke the mythic avian quality of transporting the soul. Lynryd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” peaked at #19 on the Top 40 in January 1975, “Fly Like an Eagle” by The Steve Miller Band rose to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1976/’77 and returned in 1997 when Seal’s version rose to #10. Birds & Blooms magazine crowned it “the best-ever song about birds.”

Jazz saxophonoist Charlie Parker played on his nickname “Bird” with songs titled “Yardbird Suite,” “Bird Gets the Worm” and “Bird of Paradise.” Jazz musician Paul Winter imitated bird calls on his album Flyway. The Beatles’ song “Blackbird” featured recorded bird calls.

One of Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs is “When Doves Cry,” which stayed at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for five weeks in 1984. Prince was known to keep two mourning doves named Majesty and Divinity at Paisley Park, his home outside Minneapolis. In folk tales, the mourning dove symbolized the soul of a deceased relative or friend come to comfort the living.

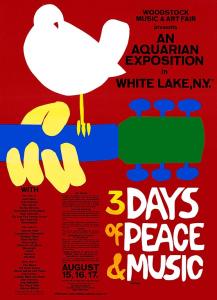

The mourning dove, a migratory bird that frequents New York State, was the bird perched on the neck of a guitar on the poster advertising the Woodstock concert in August 1969.

Learnng bird songs in Hawaii

Educators in Hawaii recently established a website to raise awareness about the many threatened birds endemic to the islands that are rarely seen anymore. Listeners can hear the unique bird calls of species only found in Hawaii (some already extinct), and also musicians playing a variety of instruments to imitate them.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: an eco-history of myth and religion, released April 2023 by John Hunt Publishing, London. Order here or at other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, which links to a pair of YouTube videos written by the author and produced by JHP.)