Long before the Romans made the arch a central feature of civic architecture, it was a sacred and universal symbol reflecting the continuous turning of the cycle of life. It was most consistently associated with sacred sites celebrating the winter solstice and the 180-degree turning of the sun from south to north, from death to life.

About 5,700 years ago, large U-shaped enclosures of stone were built near the Gulf of Morbihan on the western coast of France, according to archaeologist Aubrey Burl. The U-shaped stone enclosure at Kergonan Ileaux-Moines in Brittany was 210 feet wide and 285 feet long, capable of holding more than a thousand people. Several more were built along the coast of Britain and the east coast of Ireland, all areas that would later be homelands of the Celts. The open end of the U-shaped enclosures always faced east to the rising sun, like later Christian churches.

Burl wrote that people likely gathered inside these massive enclosures at certain times of year, entering the open end of what he termed the “horseshoe” as they might enter a church. The tallest stones were placed around the closed end, which Burl believed was the sacred location for rituals, approximately the same location as the altar in a Christian church. A container of sacred objects was found within the closed end of a U-shaped megalith at Achavanich.

Sacred architecture in the Americas

The U-shape was at the heart of sacred architecture in the Americas long before Europeans arrived.

In the Chanduy Valley of southwest Ecuador the U-shaped village of Real Alto was built about 7,000 years ago atop one of the two highest points in the valley. About 60 people lived around a central plaza and buried the dead just outside their homes.

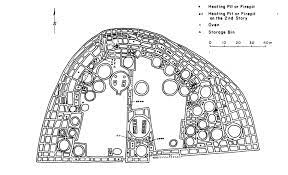

Starting about 4,000 years ago in northern and central Peru, most of the regional population was involved in building 20 U-shaped pyramid complexes. The most common chore was filling fiber bags with river cobbles and hauling them to the site. The pyramid complex at Huaca La Florida in Rimac required 6.7 million person-days to construct. At Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, the largest and best-known Great House is the arch-shaped Bonito Pueblo.

In northeastern Louisiana about 3,600 years ago Native Americans built a massive earthwork with arch-shaped concentric ridges framing a 37-acre central plaza that backs up to the serpentine Bayou Macon. Each ridge is 65 feet wide at the top with 75 feet between each one. Now known as Poverty Point, about 5,000 people once lived atop the ridges, enjoying beautiful views of the bayou. Again, most of the population was needed to build the structures. At the summit of the biggest arch-shaped ridge is the Bird Mound, the second tallest in the U.S. at 72 feet.

Sacred places and snaky rivers

Some of the most well-known sacred sites of the ancient world were built inside the U-shaped bend of a river. The Valley of the Kings in Egypt is located within one of the largest, tightest bends in the Nile River. On a high hill inside a large bend in the Yangon River, the Golden Pagoda in Myanmar is 386 feet tall and dates back 2,500 years. It was covered in gold by King Mindon in 1871 and features thousands of gems. The megalithic mound known as Brú na Bóinne in County Meath, Ireland, was built on a hill inside a bend of the River Boyne. Built almost 3,000 years ago at 10,335 feet in the Central Andes, the Old Temple at Chavín de Huántar is located between two converging rivers that form a U-shape.

It wasn’t only sacred sites that were enclosed within a large bend in a sacred river, it was entire cities.

Built at the top of a bend in the River Ganges, the city of Varanasi has been the spiritual capital of India for more than 1,500 years, a place where millions of Hindus come to bath in the serpentine river and purify themselves in one of 2,000 temples.

There are no major rivers running through Jerusalem, but the Hinnom Valley to the west and the Kidron Valley to the east were once filled with water from the year-round Gihon Spring, forming a U shape of water that defined the southern boundary of the ancient city. Early settlers dried out the valleys by diverting water into channels leading to the city. Burial tombs dating back 3,000 years have been found at the confluence of the two valleys.

Ancient capital cities defined by U-shaped bends in snaky rivers running through them include Paris, London, Berlin, Rome, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Berne, Krakow, Prague, Lhasa, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Pyongyang, Perth, and most of the original capitals in the United States, from Concord to Nashville, St. Paul, and Sacramento.

The confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers was a major crossroads and trading center for Native American tribes long before Captain John Smith arrived in 1608. Congress approved a city map in 1793 and the U-shaped area between the confluence of the two rivers became the U.S. capital of Washington D.C. in 1800.

Bisecting the arch on the solstice

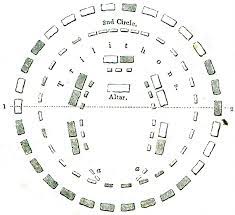

The arch was also designed into sacred sites so the rising sun on the winter solstice would bisect a megalithic U-shape.

In the Neolithic period, visitors to Stonehenge walked two miles from the snaking Avon River on a path known as the Avenue to a vantage point just northeast of the site, from which the dawning winter solstice sun appeared to bisect the U-shaped free-standing trilithons at the center of the Stonehenge circle.

In the 13th century the legendary Kublai Khan built the city of Xanadu, where Italian physicist Amelia Carolina Sparavigna recently discovered that from the vantage point of the main palace at dawn on the winter solstice, the sun rose over one large U-shaped bastion in the eastern outer wall and set over another in the opposite outer wall.

The Great Serpent Mound in Ohio was built on a ridge next to a sharp bend in Ohio Brush Creek. The rising and/or setting sun on the solstices and the equinoxes bisects various U-shaped bends in the serpent.

The symbol ‘to turn’

But if the arch form was so important, what did it represent? It’s likely that in the deep past the meaning of the arch or U-shaped symbol was familiar to everyone. Considering the contextual evidence it seems likely it was a symbol that meant “to turn.” While western culture perceives time as linear, our ancestors perceived it as cyclical, like the seasons. The symbol to turn was probably as obvious to them as a wall calendar is to us.

Nature religions always based their symbols on what was observable in the world and there are quite a few candidates for what inspired the arch or U-shaped symbol. Seeing the symbol manifest itself in nature in different ways could have been enough to elevate the form to sacredness. The arch could represent a hill or a mountain or the bowl of the sky.

A likely candidate is the Milky Way in midwinter, which appears in the form of an arch because of a visual illusion caused by its lower position in the sky. It was a near-universal notion that souls were able to ascend from earth and travel the Milky Way only when the river of stars touched the horizon.

In ancient Egyptian murals, the Milky Way goddess Net is bent over (like the downward dog in yoga), forming a U-shape with her legs as her feet touch the southeast horizon, where the solstice sun rises. Among the oldest goddesses of Egypt, Net was thought to give birth to the sun at creation – in effect, the first winter solstice, the sun’s birthday. A few days before the end of December Net also gave birth to the Egyptian pantheon of gods: Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, Seth and Horus the Falcon, according to the Greek author Plutarch.

The rainbow bridge

Another arch-shaped natural phenomenon is the rainbow, symbolic of a doorway or portal between the material and spirit worlds.

The Sumerian goddess Inanna was shown crowned with stars and wearing a rainbow necklace. The Greek goddess Iris traveled on rainbows between the two worlds, carrying messages from the gods. Hindu texts say that on the winter solstice, the sun god Surya symbolically turns his chariot north, and “wears a rainbow robe adorned with poetry.” The Sun Temple at Konark in India is a megalithic representation of Surya’s chariot.

The Taoist poet Ch’u Yuan wrote of ascending to heaven by a rainbow. For South Sea Islanders, the rainbow was a heavenly ladder used by godlike ancestors. Set in Cuzco, the Inca creation legend describes the first ancestors seeing a rainbow reaching to the volcanic mountains of the gods.

In the days of solar worship, the ancient Hebrews prostrated themselves before the rainbow. The Buddha was shown sitting on a rainbow in Bamiyan frescoes discovered in central Afghanistan. The Samoyed of Siberia say the rainbow is the hem of the cloak worn by the supreme being, Num. Shamanic figures across indigenous cultures played drums decorated with rainbows to call spirits to ceremonies.

In ancient Turkic languages, the word for rainbow is bridge. Built more than 2,300 years ago, the first Roman arch was Aqua Appia, and the pagans who designed and built it almost certainly knew that it carried at least one double meaning.

Draco’s neck

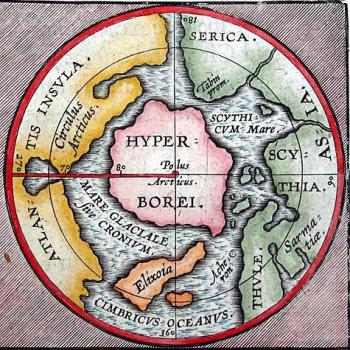

Another natural phenomenon that may be a source of the turning symbol is the arching neck of the Draco constellation.

Because the Northern Ecliptic Pole is inside the neck of Draco, the constellation appears directly overhead at dawn, fading away in the growing light. As the sun sets, Draco reappears in the very same spot. Seeing the same arching formation of stars directly overhead at both dawn and sunset must have inspired awe and curiosity in ancient cultures. An observer might easily see a fundamental connection between the arch and the sun.

In the symbolic language of ancient cultures, the shape of the arch reflected its position at the summit of the heavens. Perhaps the turning shape of Draco’s arch was considered a heavenly sign of the power to turn the sun in its daily and annual cycles.

It’s likely the importance of the arch was reinforced by its manifestation in so many naturally occurring forms. The mountain summit, the Milky Way in midwinter, the rainbow and the arch of Draco may all have reflected a belief in the continuous cycle of the universe. The nature religions warmly embraced double meanings and microcosms.

Plato’s advice was to nourish yourself with the sublime qualities of beauty, wisdom, and goodness so your soul will “grow wings” and propel you to meet Zeus and a host of gods “at the summit of the arch of the heavens.”

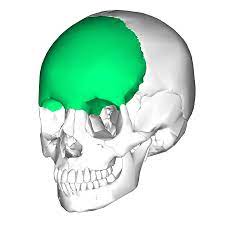

The human skull

Ancient cultures placed immeasurable value in the skull as the container of the soul, and the ritual treatment of human skulls was varied and widespread, dating back to the Neanderthals. The people of the Hula Valley in northern Israel who polished skulls with plaster and calcite crystals 12,000 years ago certainly would have noticed that the fibrous joints in human skulls form a U-shape on the front of the skull. In modern terms, the frontal lobe contains the cerebral cortex, also known as the seat of consciousness. Would it be any surprise if this was where people once believed the spark of divinity resided?

From language to song, human vocalizations resonate in the bell-shaped space formed by the U-shaped jaw, just below the cerebral cortex. Winter solstice pilgrims may have seen a link between the turning of the solstice sun from dark winter to bright sunny spring, the dawn of human consciousness and the human voice raised in communal song.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: an eco-history of myth and religion, released April 2023 by Moon Books and John Hunt Publishing. Order here or at other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, which links to a pair of YouTube videos written by the author and produced by JHP.)