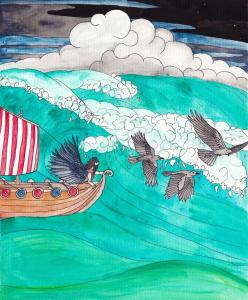

It’s well accepted that the Irish version of Christianity is more rooted in the natural world than most, so it should come as no surprise that St. Brendan may have followed flocks of migrating birds on his voyage to Iceland, just a century after St. Patrick began his conversion of Ireland.

While the Encyclopedia Britannica describes St. Brendan’s voyage as “a legendary Christian tale of sea adventure,” an impressive pile of evidence suggests it easily could have happened — it’s only 680 nautical miles from Ireland to Iceland.

Ordained as a priest in the year 512 in County Kerry, St. Brendan was an excellent mariner who established monasteries and churches from Brittany to the Orkney Islands. The possibility of his voyage to Iceland is based on written accounts, including the 9th century epic narrative Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis.

The fantastical narrative includes talking birds and a fish so big the crew mistook it for an island. Some scholars believe St. Brendan’s journey inspired the equally fantastical 9th century Irish epic Voyage of Mael Duin, in which the crew observed a very large, old and decrepit bird washing itself in a lake and miraculously growing younger and stronger. After the rejuvenated bird flew away, one of the crew jumped in the lake to bathe and never again lost a tooth or a hair.

Finding history in myth

Stories that started as oral history are usually packed with hyperbole so the story is memorable enough to survive the ages. That doesn’t mean the basic plot isn’t true. Yet the preponderance of western scholars point to the hyperbole and judge the entire story as fantastical and unreliable. Once the story is labeled mythic it disappears from the history books. But with a little practice it’s possible to find the breadcrumbs that can lead back to historical truth.

Across ancient cultures, mariners released birds to determine if land was near, dating back at least to Noah’s release of doves after the Biblical flood.

The technique was still used in 1519 on the first voyage of Hernando Cortez to the Americas when the crew was low on food and water and a dove appeared, perching on the mast. “… [A]nd all gave heartie thanks to God, directing their course the way the Dove flew.”

The traditional version of Norse mariner Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarsson’s discovery of Iceland in 874 describes him releasing three ravens, the last of which led him to Iceland. A more esoteric version has Flóki performing a ritual before the journey to join his soul with the ravens. Danish scholar Wilhelm Gronbech wrote that Flóki was made into a “raven-man (who) flew with unerring instinct over the sea.”

The 12th century Icelandic chronicle Íslendingabók says when Flóki and his crew arrived in Iceland they encountered Irish monks, who they named papars. The monks – who were trying to quietly pursue spiritual goals – fled the Vikings, got in their boats and left.

The new evidence

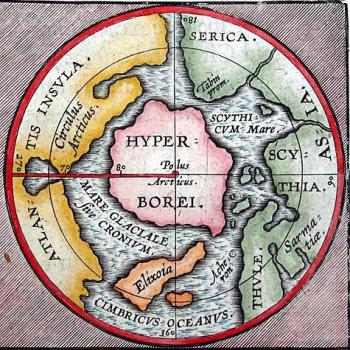

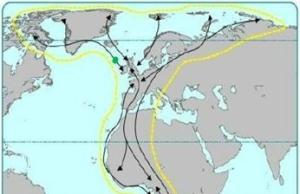

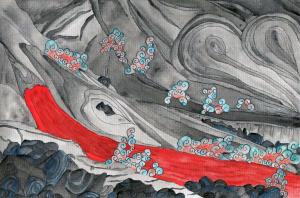

St. Brendan and his mariner-apostles reportedly left on their voyage to a “promised land” from Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry, which happens to be at one end of the only bird migration route that links Ireland to Iceland. The route is part of the East Atlantic Global Bird Migration Flyway.

According to mapping by BirdLife International, the flyway carries large waterfowl such as Greenland white-fronted geese and whooper swans. Starting in County Kerry the migration route passes over three small volcanic islands about 300 nautical miles northwest of Ireland before continuing about 380 nautical miles to the west coast of Iceland and then beyond to Greenland.

Located about halfway to Iceland, the tiny islands serve as an avian rest stop, especially in bad weather. The islands were likely covered with large, loud waterfowl, perhaps inspiring the notion of talking birds in the Navigatio Brendani. The story of the old bird that grew younger and flew away in the Voyage of Mael Duin may simply be a memorable way to say the islands were a rest stop.

The Rockall Plateau fishery

Better yet, the small volcanic islands of Rockall, Hasselwood Rock and Helen’s Reef are located on a plateau long known as a fishery for haddock, gurnard and monkfish. In the Navigatio Brendani, St. Brendan and his crew come ashore what they think is an island but turns out to be a giant fish or sea beast. In the Voyage of Mael Duin, the mariners spear salmon that are jumping over the boat. These fantastical events were likely the storyteller’s memorable way of saying that St. Brendan and his mariners came across plentiful fishing on the Rockall Plateau.

According to Irish legend, St. Brendan was inspired to make the journey north by a monk named Barinthus, who told a story about a land of promise just a 40-day sea voyage from Ireland. In 1976, explorer Tim Severin successfully demonstrated that St. Brendan’s voyage was possible by sailing a period-correct leather curragh from Ireland to Iceland and Newfoundland. In a quirky twist of history, Severin’s entire trip took 40 days, from May 17 to June 26.

St. Brendan and his mariner-apostles could easily have made it to Iceland in 40 days, including a couple of days to fish the Rockall Plateau.

Following birds in the ancient world

A rich vein of stories tell of people following the guidance of birds on long-range treks.

When Jason and the Argonauts approached the Clashing Rocks, they released a dove to see if it could get through. The dove flew through the perilous boulders with only a slightly clipped tail, and Jason’s ship followed, losing only the tip of its prop.

Some stories about following birds were recorded as true events. After the Greek island of Santorini was destroyed by a volcanic eruption about 3,600 years ago, it was said that ravens guided the people of Thera to their new home in modern-day Libya. In fact, a bird route on the Mediterranean/Black Sea Flyway runs just west of Santorini and heads south to the Libyan coast. (Ravens are common in the Aegean Sea but are not migratory birds.)

In Plutarch’s Life of Alexander, a flock of ravens came to the rescue of Alexander’s army and put them back on course. “When the guides became confused over the landmarks and the travelers got separated, lost their way and started wandering about, ravens appeared and took over the role of guiding them on their journeys,” Plutarch wrote. “What was most remarkable of all, we’re told, was that they called out to those who strayed away at night and by their croaking set them back on the right track.” Still another story tells of ravens guiding Alexander through the desert to the Oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis in northwest Egypt, a sacred site established by Zeus himself.

The mystical divinity of volcanoes

The overriding special quality of the promised land St. Brendan sought was described in volcanic terms, according to Thomas O’Loughlin of the University of Nottingham in England.

In his essay, “Distant Islands:The Topography of Holiness in the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis,” O’Loughlin wrote that St. Brendan’s promised land was perceived as “an island where there is a brightness unlike any other … which needs neither sun nor moon … Now we have left our world and entered into a place where the divine is closer and less veiled … ”

It would be no great surprise if the mystical attraction to Iceland was related to its rivers of lava glowing brightly through months of darkness and billowing with steam as hot magma hisses into the sea. Most pagan cultures believed a spirit world existed below the waters and the earth and volcanoes were typically the home of powerful divinities, often related to creation.

Officially, there was no hell until after the Hekla volcano in Iceland erupted in 1104, centuries after the Irish and Norse had braved the seas to settle there. After the 1104 eruption, Herbert the Abbot of Clairveaux in northeastern France declared two official portals to hell: One was Hekla (the eternal prison of Judas) and the other was Mount Etna in Sicily, where hell was said to be visible from the crater’s edge.

(Ben H. Gagnon is an award-winning journalist and author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming March 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, now available for pre-order. He’s also author of People of the Flow (Beacon Publishing Group, 2019), a novel of historical fiction that explores Irish megaliths through the lens of the Celtic Revival in early 20th century Ireland, available here.)