It all started in the spring of 2014 during a visit to the 5,200-year-old megalithic mound known then as Newgrange, sitting atop a hill inside a bend of the River Boyne in County Meath, Ireland, about 35 miles north of Dublin. (In a welcome act of cultural sensitivity, the mound is no longer named after the English landowner who effectively seized the property in the late 17th century, but has been officially changed to the age-old Gaelic name for the mound, Brú na Bóinne.)

There’s no question a tribe of Celts settled in the Boyne Valley at some point, probably about 3,500 years ago, and they likely arrived by the tidal River Boyne. Coming just six miles inland they would have encountered the ruins of Brú na Bóinne, including a massive pile of white quartz stone that had broken off from the mound. Two other megalithic mounds, Knowth and Dowth, would have been found within a mile.

A discovery for the ages

Imagine the amazement of the Celtic tribe as they came across the remains of such massive structures in the middle of a beautiful wilderness. They must have known they’d found a sacred place. During winter the plentiful salmon swimming up the Boyne to spawn were far larger than today’s version. Adding to the beauty and drama of the scene – if it was between late November and early April – would have been a huge flock of whooper swans with nine-foot wingspans, chatting and calling amidst the ruins.

Considering the unparalleled mythic status of the whooper swan across its entire habitat, the bird was likely already sacred to the Celts before they encountered the flock in the Boyne Valley. It was no surprise they were looking at one of the most fertile valleys they’d ever seen, thanks to millennia of droppings from thousands of whoopers weighing up to 30 pounds apiece. The obvious fertility of the valley had likely attracted the settlers who built the mounds long before.

Shape-shifting into swans

On the bus that made its way through cow pastures to the ancient site, the tour guide related a legend about the Tuatha Dé Danann shape-shifting into swans and singing beautiful music. He further noted that a flock of whoopers still winters in the Boyne Valley, though much diminished from the days when the legend was first told.

I’m six-feet tall but it was a surprisingly comfortable walk down the 60-foot passage to the oblong central chamber inside Brú na Bóinne, which comfortably fits about 10 people. Most incredible was the corbeled dome: A ring of massive stone slabs piled on top of each other with each sticking out a bit farther to form the 20-foot dome. Before the pandemic, about 30,000 people entered a raffle each year to be literally and figuratively illuminated in the central chamber when the sun shines down the long passage at dawn on the winter solstice.

While no photos were allowed inside I joined many others taking pictures of the Neolithic-era designs that covered many of the massive kerbstones that surrounded the base of each mound. It seems 75 percent of all Neolithic rock art is in the Boyne Valley. K-15 was one of the kerbstones surrounding the base of the Knowth mound and boasted more complex features than any other.

The mysterious K-15

A few weeks later a closer look at my photo of K-15 revealed several curious features suggesting it had been turned upside down at some time in the past. Looking at K-15 as it sits today. the bottom of the stone appears shaped into a triangle with the tip out of view, buried in a jumble of small stones. Meanwhile there’s a straight horizontal line near the flat top of the stone, above which it is substantially darker.

When I flipped the picture vertically on my laptop (see photo) the images on K-15 started to make more sense. Perhaps the horizontal line on the stone was created by being partially buried in soil or submerged in a shallow pool. In the middle is what appears to be a semi-circular sun with rays extending, as if dawning on the horizon. I knew this to be the symbol on the flag of the Fianna, the law enforcement arm of ancient Ireland, but Knowth was built long before the Celts arrived, so I thought the parallel was coincidental.

Scholars believe the original builders of Knowth and the two other mounds abandoned the sites within a thousand years or so, and I soon learned that when Neolithic peoples abandoned sacred sites they practiced rituals to “shut off ” the connection to the cosmos. Maybe the kerbstone had been turned over to hide its secrets.

Inspired to further research, I found K-15 was the subject of a book claiming it was the oldest sundial ever found, as reported on the website Knowth.com. Other scholars disputed the claim. As far as I could tell the author was an independent researcher who at some point had left Europe and couldn’t be contacted. There was no mention on Knowth.com of the kerbstone being upside-down, which I thought would be an important factor for a sundial.

Is there a swan on K-15?

I discussed the matter with my friend Geoff Ward, whom I’d met at a reunion concert of the psychedelic-folk band Dr. Strange and the Strangelies held in a modest art gallery right on the harbor in Castletownbere, County Cork. Geoff was a journalist in Britain for much of his adult life and is now an author and writer for Medium.com and other outlets. He’s long been fascinated by the megaliths of Europe and ancient cultures in general and is part of an online community of like-minded people. Looking at the photographs at his home in Castletownbere, Geoff agreed the stain was unusual.

When I flipped the photo vertically I saw the faint outline of what appeared to be a swan to the right of the radiating sun. Certainly a swan carved in stone on the wintering grounds of swans would not be surprising in itself. If it was a swan, the image could easily have gone unnoticed for centuries if K-15 was turned upside down.

To the right of the radiating sun, the swan appears to be shown in profile with its head facing left. The eye is over-large, but the lines of the head seem clear, while lower down are lines that suggest a curving neck and body.

I thought it could be a case of pareidolia, in which case my brain’s fusiform gyrus constructed the pattern of an animal from a random series of cracks. Worse yet I was reading the swan myths of the Tuatha Dé Danann at the time, so perhaps I was seeing something an entirely different part of my brain was hoping to see. Who doesn’t want to discover something new at an ancient sacred site?

And there’s another thing: The swan would be the only naturalistic image in the Boyne Valley, where the Neolithic art is made up of spirals, concentric circles, diamond-shapes, wavy lines, cross-hatching and other geometric forms.

Making a fuss anyway

Maybe K-15 wasn’t decorated by the dark-skinned Anatolian farmers who probably built the mounds after arriving in the Boinne Valley from the Near East about 6,000 years ago, according to genetic studies. Perhaps the stone was carved much later by the Celts, who arrived long after the area was abandoned by the original builders. That would explain the naturalistic image.

Maybe K-15 was created and used by the Celts for some unknown ritual involving the dawning sun. After the last pagan king surrendered his throne at nearby Tara 1,500 years ago, maybe the stone was turned upside down to extinguish its power.

The strongest evidence of something unusual is the stain and the shape of the stone, both suggesting that at some point K-15 was turned upside down. I was happy to leave the possibility of a swan image to the experts, but Geoff and I wrote a letter to Ireland’s Office of Public Works Historic Services commissioner asking that K-15 undergo forensic tests to determine what the stain was all about.

While our letter went unanswered, Geoff wrote an article for Medium.com in July 2019 attracting 2,300 “views,” 835 “reads” and hundreds of comments on Facebook (see article here). Anthony Murphy, a photographer and researcher specializing in the Boyne Valley, commented that there was no swan image on K-15, and that whatever people might be seeing was only random cracks in the stone.

Murphy shared an infrared photo of the stone that showed no trace of the swan image. Perhaps an infrared photo in this case is definitive in some way, but I can’t help thinking that the people who decorated K-15 never saw it in the infrared spectrum. Whatever they were trying to communicate was in the human visual spectrum.

Overall, what bothered me about Murphy’s response was he didn’t address the stain on the stone, the shape of the top and bottom of the stone, and the question of whether it had been intentionally turned upside down as part of an abandonment ritual. After all the site had been abandoned twice by two different pagan cultures. And what about the coincidence that the semi-circular rising sun was the iconic image on the flag of the ancient Irish Fianna?

A link to the winter solstice?

Meanwhile this daisy chain of a story has one more chapter to unfold, and I’ll admit it’s linked by the most tenuous thread of all, more like a swaying rope bridge, but on the other side is a bounty of circumstantial context supporting the possible swan image on K-15.

Here’s the tenuous part: If one or more druids stood behind K-15 and gazed over the triangular top of the stone at its reflection in a pool, the image of the swan’s head would appear at the upper left, facing the semicircular, halfway risen sun. At this point it’s helpful to remember that Roman observers reported druids practicing divination by staring into water, a practice known as scrying.

Meanwhile the motif of a bird to the upper left of a semicircular or arching shape can be found across ancient and indigenous cultures. Soon I had collected a list of sacred images, most of which are too difficult and/or costly to publish, but can be found online.

1) On the 2,100-year-old Gundestrup Cauldron, the head of a Celtic-style Apollo is inside an arch-shaped headdress, while his right hand touches a bird at 10 o’clock.

2) A 4,300-year-old Akkadian cylinder seal shows a Sumerian creator god inside the bend of an arch-shaped river of fish, touching a bird at 10 o’clock with his right hand.

3) At least two murals of the Egyptian goddess Net show her as the embodiment of the Milky Way with her body bent in an arch with a bird at 10 o’clock.

4) A Fremont pictograph in Utah created between 1,400 and 700 years ago shows a large arch with an owl at 10 o’clock. The Fremont buried stuffed owls with their dead.

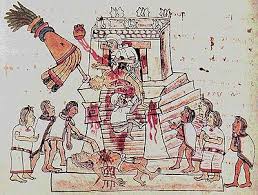

5) The Aztec Codex Megliabecchi includes a painting of a human sacrifice dedicated to the sun god Huitzilopochtli in which the victim is bent backwards to form an arch shape, with a bird symbol at 10 o’clock. The winter solstice was a time of human sacrifice to the sun god.

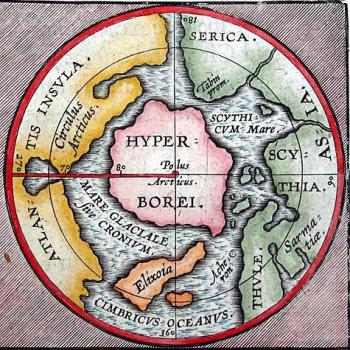

Around the winter solstice, Cygnus is at 10 o’clock relative to the arch-shaped neck of Draco, suggesting the motif was a cosmic clock to identify what was the most important day of the year across solar-oriented cultures of the ancient world.

It would be surprising if the winter solstice was not associated with a simple and widely known visual icon. Each week as the solstice approached, the cosmic alignment everyone was waiting for moved steadily into place, like a countdown before the big day.

(With regard to K-15 and the tenuous theoretical reflecting pool, there would have been no more popular day for scrying and divination than the winter solstice, the ancient equivalent of New Year’s Day.)

Pareidolia or history?

If the image on K-15 is a swan and not a series of fortuitous cracks, this context makes it more likely that K-15 was part of a winter solstice ritual.

But it doesn’t answer the question of who created the image. For all we know the Anatolian farmers had never seen whooper swans before arriving in Ireland and made the image in its honor.

Neither context nor speculation makes the image itself look any more or less like a swan; unfortunately the low resolution of online photos doesn’t help. Another version can be found here — scroll down near the bottom of the page to the photo of K-15 with a caption saying it was taken during excavations.

So the image is either a case of pareidolia augmented by reading lots of Irish mythology or the oldest example of a cross-cultural winter solstice motif that’s been around for more than 5,000 years.

I’m still looking forward to that study of the mysterious stain.

(Ben H. Gagnon is the author of Church of Birds: An Eco-History of Myth and Religion, coming in April 2023 from John Hunt Publishing, London; now available for pre-order. A version of this story is the book’s afterword.)