I do my exercises faithfully. Not only because I had back surgery fifteen years ago, nor even only to address the labral tear in my hip. Easter comes in the Spring, and Easter means three hours of standing. For a person in my frail physical condition, three hours of standing can be excruciating. But I wouldn’t miss it. Hence, the exercises.

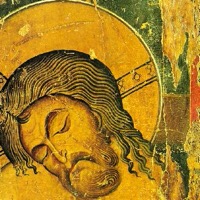

Around ten in the p.m. on April 11, I’ll drop two Alleve and wander over to St. John Orthodox Church near my house to stand through the Midnight Office and Divine Liturgy as an outsider among the faithful, to breathe the incense, to feel the Easter troparion, to walk the short procession with the candle in my hand, out the back way and around to the closed doors at the front of the church where one or another of the resident priests, above us at the top of the steps, will knock, loudly, three times, and cry out to the dark, Memphis neighborhood “Christ Is Risen!”

It’s a lovely moment. One of the chief moments that keep me going spiritually for the year.

It’s a little sad, I suppose, that I have to outsource my spirituality. It’s not really sad. Mormonism’s claim to encompassing all truth means it can accommodate worship in multiplicity; so, you might say that I’m not outsourcing at all, but merely finding divinity where it happens to appear.

But it is a little bit too bad that LDS ceremonies feed my spiritual longing as little as they do. Not only the Orthodox liturgy, to which my Memphis neighborhood gives me such convenient access, but the basilicas of old Europe, the pilgrimage sites I’ve touched in the Czech Republic and Spain, the Buddhist shrines I have visited in China, and the religious charge the Vaishnava mandirs and Sikh gurdwaras offer me when I am in India, bring god closer to me than the chores of the LDS week.

Yes, apples and oranges. Not fair to compare a typical Sunday service in an LDS chapel to the extraordinary experience of mass with the Infant of Prague or an abhishek in Radharaman mandir. But LDS Mormonism offers so little that could be compared to mass with the Infant of Prague. What’s worse, LDS church culture so earnestly tries to smother good faith interest in seeking the lovely things of good report that LDS culture lacks.

There is, of course, the LDS temple, which certainly has the potential to be high ritual that can help Mormon life claim the cycle of the year and transcend the ennui of mundane life. But (setting aside the horrifically patriarchal demands of the endowment for the moment) LDS temples are made for work, so they prove consistently unsuitable for occasions that call for an aesthetic indulgence for which the temple can spare little time. Even if we did chase the wild hare to have an Easter Midnight Endowment, the temples aren’t built to accommodate the people who would show up.

For their part, Mormon chapels are designed to minimize costs and to maximize efficiency. Some of us find them to be such poisonously bland spaces that we go to ward meetings to commune with auxiliary leaders, and then go elsewhere to commune with god.

It’s not that I would have the church transformed to suit my own “high church” sensibilities. Not everyone’s keen on incense and chanting, and I’ll be the last to demand that the church develop spaces and rites only to satisfy me.

Quite the contrary: I am bewildered by LDS folks who presume themselves faithful for demanding that the church cannot open, for anyone, in any way, to the bright, holy life that other communities offer. When Eric Huntsman finds in a By Common Consent post that it is “needless to say” that a stake presidency of his youth “shut down” a Mormon bishop’s plan for a Palm Sunday procession, he confesses the sad truth that LDS Mormons have come, simply, to expect their church to close off opportunities to encounter god and that they simply expect the church to place itself between its members and the rest of humanity.

What the LDS church does not provide, Mormons should not be afraid to ask of their neighbors. Mormons cannot progress as individuals and as an institutional body while they set aside as inconsequential or suspicious all that everyone else has discovered about god. It is not always appropriate to participate in another community’s rites. But this propriety ought to be determined more by the ideology of the other community than by a sense that Mormonism was meant to isolate Mormons from everyone else and to preserve Mormon spirituality in a jar.

Perhaps god miscalculated the effect of telling Mormons, first, that all the Christian sects of early nineteenth-century New England were wrong, and, second, that the LDS church is the only true and living church. An unfortunate outcome has been the development of a culture that fears or demeans the genuine devotion that is available in the world, and that resists the plain implication of Mormonism’s fundamental articles of faith—that the LDS church institution does not now offer all the great and important things pertaining to the kingdom.

The church has a form and function which might be sufficient for its present purposes, but to confuse that form and function, as we so often do, with an exclusive prescription for our spirituality is to deny the very foundation of Mormonism.

I will stay up most of the night prior to Easter morning, and I’ll spend at least three of the wee hours standing in someone else’s church for someone else’s service. I’ll be half asleep during the three-hour block of Mormon services the next day, and, on account of my impaired faculties, I will probably mess up badly the musical number which I am supposed to accompany on the piano.

It’s a fair trade.