‘Dead, mad, or a poet’ is a phrase we hear sometimes in various branches of Celtic-inspired paganism. Having heard it repeatedly I began to wonder where exactly the phrase came from and how it related to folk belief, and this led me on a quest to see if I could find out. Like so many things the answer turned out to be both simple and complicated.

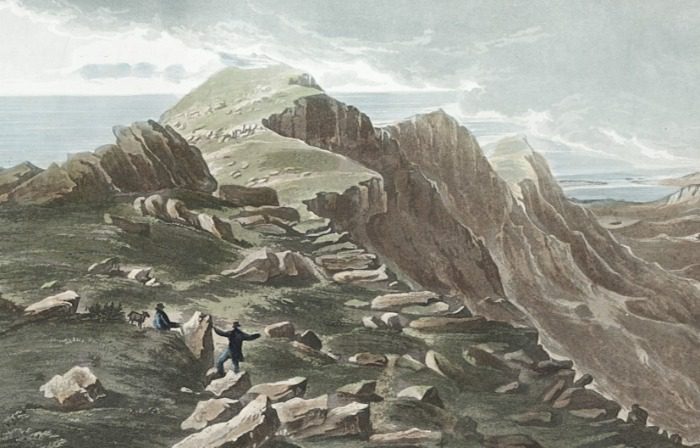

The exact quote itself is from Robert Graves’ 1948 book The White Goddess. Page 19: “There is a stone seat at the top of Cader Idris , ‘the Chair of Idris’, where, according to the local legend, whoever spends the night is found in the morning either dead, mad, or a poet.” Now Graves has a reputation for being quite inventive with the source material – let us not forget his creation whole cloth of the ‘Druidic goddess’ Druantia or the tree calendar – so once I realized the quote came from Graves my next question, logically, was: did Graves make this up himself or was he repeating something older?

Folklore

There’s certainly a lot of folklore backing up the wider concept of going to a sacred place, often one associated with the Good People, and sleeping there to acquire inspiration or to be driven mad for one’s hubris. We see this in some versions of the story of the Brahan Seer, Coinneach Odhar, a Scottish seer who may have been given his gift after sleeping on a fairy howe and waking to find a holed stone resting on his chest. In the same way Turlough O’Carolan, a famous blind Irish musician of the 17th century, was supposed to have gained his skill and many of his songs by sleeping on a fairy hill.

In the folktale of Lus Mór [Foxglove] the eponymous main character was a man with a hunched back who fell asleep on a fairy hill and woke to hear the inhabitants of the hill signing; when he joined the song at the exact right moment with a new line for the song the delighted Fair Folk healed his back. However when another man with a similar hunched back tried the same thing but interrupted the song rudely mid-verse he was punished by having his back twisted twice as badly. These are only a few examples of the substance behind the concept, the idea that risking everything by being vulnerable in the Good People’s places can bring either great reward or great danger, sometimes both. I might suggest, from my own perspective, that there seem to be potential hints here of what could be initiatory rites relating to the practice of sleeping on or going into the sí, but that’s a topic that would take a whole other article to unpack.

Welsh Sources

Now I knew that the concept was genuine, but that the quote itself came from a mid 20th century source of questionable integrity. That led me to keep digging to see what else I could find. In researching the roots of ‘dead, mad’ or a poet’ and trying to find Graves unnamed source I found an 1874 entry discussing Cader Idris in the 1884 book ‘Bye-Gones, Relating to Wales and the Border Countries‘ which says: “There is a popular Welsh tradition that on the summit of Cader Idris is an excavation in the rock resembling a couch and that whoever should pass a night in that seat would be found in the morning either dead, raving mad, or endowed with supernatural genius.” It would seem likely from the similarity in wording that this or another identical such source from Welsh folklore influenced Graves’ later writing.

The same text mentions that this idea was not unique to Cader Idris but was found in other areas of Wales as well, and offers the example of Maen Du Yr Arddu [black stone of Arddu] where it was said if two people slept on the eponymous stone one would go mad and the other become a poet. The Maen Du Yr Arrdu example is particularly interesting to me, because while Cader Idris offers three possibilities for a single person Maen Du Yr Arrdu implies that two people must go in and one is guaranteed inspiration and the other madness. The Welsh material differs from the above mentioned Scottish and Irish folklore only in that there is no explicit connection with the fairies there, however if we look elsewhere in Welsh folklore we do find that Cader Idris was known as a habitation of the fairies and Maen Du Yr Arrdu is near a lake, Llyn Du Yr Arrdu [Black lake of Arrdu] associated with the Tylweth Teg [Fair Family aka fairies].

Graves was a controversial figure in many ways, inspired and far more influential for modern paganism than many people give him credit for but also prone to invention that he freely attributed to non-existent historic sources. His legacy is a muddle of his own poetic license: new material born of his imagination and genuinely older material re-dressed and re-told in his words. In this case however we see an example of Graves repeating genuine folklore and as a poet with a way with words doing so in a very evocative way. ‘Dead, mad, or a poet’ is not only concise but beautiful, certainly more so than ‘dead, raving mad, or endowed with supernatural genius’. That second one hardly rolls off the tongue. And in this case he manages to convey both the potential gain and genuine risk that comes from engaging with these Otherworldly powers.

So if you are feeling brave and you are willing to risk your life and your sanity to gain the gift of prophecy and magical speech, you might consider going out and sleeping in the sacred space of the Fair Folk – just remember that no one can truly tell you what they will ask of you in trade. And in the morning you will wake, if you wake at all, ‘dead, mad, or a poet’.

References:

Mackenzie, A., (1899) The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer

Askew, R., (1884) Bye-Gones, Relating to Wales and the Border Countries

Graves, R., (1948) The White Goddess

Pennick, N., (2015) Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition

Thomas, J., (1908) The Welsh Fairy Book

Halliwell-Phillips, J., (1860) Notes of Family Excursions in North Wales

Rhys, J., (1907) Celtic Folklore Welsh and Manx