If you are new to Celtic Paganism, you probably have a lot of questions about what Celts did in the past, the right way to honour the gods, the meaning of the myths, and so on. You may be searching for good books on the topic, or just a bit of casual advice about things. I see people reaching out for information almost every day, and often getting unsatisfactory answers. On the one hand, self-appointed experts may hit them with a long list of things they “must” read or laugh at the sources they’ve tried so far. On the other hand, there is a faction who are fond of saying things like “just find your own path” or “everyone has different ideas about these things”. A generous attitude, but not very informative.

The truth is, finding good information about early Celtic beliefs takes effort, and most of it comes from academic sources or from Pagans with an academic approach to things. I think this is something the Celtic Pagan community needs to work on, because not every sincere seeker into our path has the patience, education, or access to obscure and expensive books to do this work for themselves. I’ve written about getting into Celtic mythology before, but the rest is messier.

I want to help you understand why it’s so messy, and to warn you that the truth about what early Celts believed or what their religious practices were is largely unknown. So, if you encounter someone making hard and fast statements about this stuff, ask to see the evidence. There is nothing wrong with people making educated guesses, and there is nothing wrong with personal gnosis or personal preference. The trouble starts when people state their opinions as if they were provable facts.

Both internet pundits and some Pagan authors are prone to making statements like “The Celts worshipped the sun and the moon.” “Brigid was a fertility goddess!” Declarations like these are a major red flag. A good source will probably say things like “The Celts might have done ___ because this particular Roman writer mentioned it.” or “Archaeologist Susan Smith found inscriptions to the same goddess at six different Iron Age pig farms, but none of the inscriptions actually mentions pigs, so it could be coincidence.” There are good books based on personal gnosis and opinion, too. One of the things that makes them good, is that they don’t pretend to be something else.

The classic definition of history is something like “The study of the past through written documents.” That definition is beginning to change as we become more confident in disciplines like archaeology, oral history, linguistics, and genetics. However, adherence to the written word is a hard habit for historians to break. This makes the study of the Celts problematic because they chose not to use writing to record their history, genealogy, laws, or mythology until the medieval period. (To put this in perspective, writing was a part of Greek culture some 2,000 years earlier.) Not all Celts were illiterate. A few Iron Age Celts could read and write Greek or Latin, for example, but as a culture they valued oral transmission and avoided the written word. As with so many things, the reasons for that choice are lost to us.

Most of what we have long believed about the ancient Celts comes from the writing of the Romans, and the vast majority of that from one man, Julius Caesar. Historians have taken the position that he would know, because he was there. Caesar built his imperial career out of making war on the Celts, and wrote a memoir of his exploits. but scholars question whether he really witnessed everything he described, or whether some of it was hearsay, or even plagiarism. Anyway, we must wonder whether Romans were simply writing propaganda against the Celts, or bending the truth for personal reasons. The Romans generally portrayed the Celts as noble and exotic savages.

The Celts are not the only culture to have suffered from historical misunderstanding when their oral traditions met the force of a mighty military power which destroyed their culture and then got to write the story of who they were. The same thing happened to the native peoples of Africa and the Americas during their invasion and subjugation by Europeans in recent centuries.

European scholars have not questioned the Roman writers enough, largely because they identified with them as literate, urbane and civilised colonisers. Until recently, most western historians comparing Rome to the British Empire or the United States, have done so proudly. We have finally begun to let go of our belief in the rightness of powerful nations imposing their “improvements” on everyone they encounter, but there is still a long way to go.

Archaeology is another way we can learn about the past, but without contemporary written material, everything is open to interpretation. Is that piece of art religious, or not? Was that Latin inscription left by a Roman, or a Romanised Celt? What do burial practice tell us about belief? And the most basic question of all, is the stuff we’ve dug up even Celtic?

“Celtic” is an evocative word, but not a very specific one. Is it defined by language, geography, culture, or genetics? Many academics limit the definition to speakers of Celtic languages during the Iron Age, and perhaps a few centuries beyond. This appears to remove a lot of gray areas, but real life is full of gray areas. For example, many people living in Scotland, Ireland or Wales today consider themselves to be Celtic because of cultural differences and/or genetics, regardless of what language they speak. Did Celts in other times define themselves by language? We don’t know. We don’t even know whether they defined themselves as Celts, or just as Aedui, Iceni, Epidii, etc. The genealogy of dynasties was considered very important, but there is no evidence that “racial purity” was.

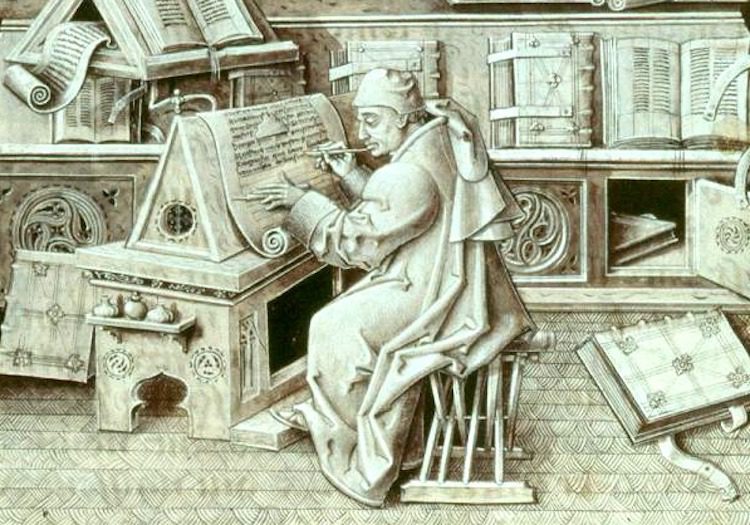

As the Romans faded from the picture, Germanic peoples vied with the Celts for power and territory, and their cultures undoubtedly influenced each other, although neither side left much in the way of written records until the Medieval period. By the time scribes finally began setting the myths, laws, history, and poetry of the Irish and Welsh down in books, much of the material was fragmented. We can’t always tell, a thousand years later, how “authentic” some of these texts are, or how old the ideas in them are. Most of the scribes must have been fluent Welsh or Gaelic speakers, but both their methods and their agenda are unclear.

In modern times, “Celtic culture” is frequently reduced to clichés and repackaged by corporations for consumption by all. Our dramatic landscapes, delicious beer and whisky, our wars, our music and mythology, even the way we speak English, become one dimensional tropes, easily cut and pasted to suit the occasion, or marketed as a package tour. Celtic spirituality, Paganism and Polytheism often get the same treatment and sadly, some of the stereotypes are perpetuated by the Pagan community.

This little essay isn’t meant to discourage you from doing research, or from taking an interest in anything Celtic that strikes your fancy. Just beware of glib pronouncements about how things were with the Celts of prehistory, or even during parts of the historical period. Much of what they believed, what their daily lives were like, or what their religious practices were, is lost to us. All of us tend to interpret the evidence to suit our own theories and beliefs, even if we think we don’t. Take time to stop and consider the things you read about Celtic history, mythology, religion, and culture. Are writers basing their statements on study, or fantasy? Did they study a reliable source? Is there an agenda behind their statements?