While exploring the public articles on the wonderful Oxford Islamic Studies Online website just now, I came across this valuable overview of Shariah by William & Mary professor Tamara Sonn.

A while back I wrote some (far less inspired) entries on other, comparably complex and misunderstood topics in Islam for a reference work (the table of contents of which is unfortunately and inexplicably nowhere to be found online), so I appreciate the sophistication of Sonn's piece. It's the scholarly equivalent of parrying blows from a crowd of attackers like a Kung-Fu master when you correct so many misconceptions on various levels while still managing to keeping things accessible, objective and succinct.

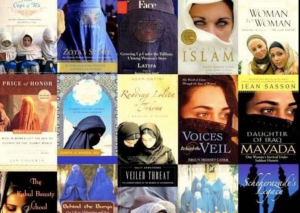

This piece also shows you how utterly, scandalously, and irremediably out of touch sensationalistic MSM debates about the state of Muslim thought often are. (And, sadly, a fair number of debates about Shariah in Muslim countries, as well.)

Earth to Islamophobes: Have some intellectual honesty and grapple with the nuances raised in articles like this as you craft your straw religion.

An excerpt from "What is Shariʿah?"_by Tamara Sonn – Oxford Islamic Studies Online

The body of Islamic law does undoubtedly contain elements that are startling in the light of contemporary Western norms. And today, there is lively debate among Muslim scholars over many of the laws that most concern non-Muslim observers, particularly those dealing with democracy, pluralism, the rights of women and of minorities, and the status of the traditional ḥudūd punishments.

Many contemporary Islamic thinkers fully endorse pluralism, including full equality for all citizens. Egypt’s Fahmiʿ Huwaydiʿ, for example, argues for equal rights for non-Muslim minorities based on the overall goal of Islamic law, which is to establish justice. In order to achieve justice in today’s world, he says, democracy is essential. Democracy has been shown to be successful in the West, and it is the most effective way to implement the Qur'ān’s command to govern through consultation (shūrā). While shūrā has been exercised in various ways throughout history, in order to result in justice today it must be anchored in a government that recognizes the right of people to choose their ruler, and this right must be shared equally by all citizens. Egyptian legal scholar Salim al-Awa (Saliʿm al-عAwwā) also argues in favor of democracy, saying that Islam places authority with the people, and all citizens have equal rights to choose, women and non-Muslims included.

Exiled Tunisian thinker Rachid Ghannouchi (Rāshid Ghannūshiʿ) argues for Muslim participation in secular democracies, again based on the Qur'ānic principle of participatory governance, shūrā, which he defines as the authority of the community. Muslims must work with whoever is willing to help achieve essential Islamic goals such as “independence, development, social solidarity, civil liberties, human rights, political pluralism, independence of the judiciary, freedom of the press, or liberty for mosques and Islamic activities.”

Leading European Muslim scholar Tariq Ramadan concludes that any government conforming to Islamic principles must allow for communal consultation, including both men and women, and that the most efficient means of doing that today is through a consultative council made up of elected members. He also insists that any representatives be chosen on the basis of competence in various areas pertinent to daily life, rather than heredity or some other unearned criterion. This competence allows them to exercise ijtihād, that is, to deliberate and formulate ways to achieve Islamic principles in today’s circumstances, instead of relying on models appropriate to circumstances that no longer exist. Consequently, Ramadan concludes, Islam is completely opposed to theocracy. Not only must Islamic government be conducted through consultation, it also requires freedom of conscience. This is based on Ramadan’s reading of the Qur'ān’s prohibition of compulsion in matters of religion (2:256). Thus, he says, people must have the right to choose their leaders, express their opinions, and live—male and female, Muslims and non-Muslim—under equal protection of the law, as was the case in the Prophet’s time under the Constitution of Medina. He argues that, although there is no unique model of Islamic government, basic principles have been provided which Ramadan calls “a framework to run pluralism.”

In a similar vein, Ramadan recommends a moratorium on the implementation of ḥudūd punishments. Other scholars agree, focusing specifically on the prohibition of apostasy (renouncing one’s religion). For example, the former chief justice of Pakistan, Dr. S. A. Rahman, argues that the prohibition of apostasy under threat of capital punishment violates the Qur'ān’s fundamental insistence on freedom of conscience. Egypt’s highest religious authority, Grand Muftiʿ Ali Gomaa (عAlī Jumعah), also rejects the death sentence for apostasy, arguing that if punishment is due, it will come in the afterlife. There is even debate about whether or not some of the ḥudūd punishments have been properly understood and interpreted in the first place. Tunisian historian Mohamed Talbi explains that the law requiring capital punishment for apostasy resulted from a confusion of apostasy with treason. Leading American Muslim scholar Professor Ali A. Mazrui takes a slightly different approach. He argues for rethinking the ḥudūd punishments, saying that the punishments laid down fourteen centuries ago “had to be truly severe enough to be a deterrent” in their day, but “since then God has taught us more about crime, its causes,the methods of its investigation, the limits of guilt, and the much wider range of possible punishments.”

There is wide ranging opinion regarding precisely which laws should be subjected to ijtihād. It is common for conservative scholars to identify the laws they believe should be preserved as shariʿah and therefore not subject to ijtihād. Reformist thinkers tend to place greater emphasis on the distinction between shariʿah and fiqh. This discussion has been a feature of Islamic discourse throughout history.

A sub to this site looks like a really nice Christmas Eid present to grad students.