We need to make an honest examination of our beliefs. We need to, prayerfully, come before Christ and lay it all out on the line with fear and trembling for what the results may be, but with fear and trembling nonetheless. We have to do this, and it should be difficult because we’re Christians and the Christian life is not an easy ride. We forget this. We need to constantly examine our motives and consider our opportunities. We need to honestly ask ourselves where the Lord is leading and what He is doing and how we are responding and we need to do these things because that’s what we’ve signed up for.

And we need to do this with grace.

As a Protestant I believed that grace came directly from God. If you’d told me that I needed a pastor, in the middle, I would’ve looked at you sideways. If you’d told me that God needed anything to mediate out His graces, I would’ve told you you’re crazy. Grace, I believed as a Protestant, came directly from God with no need of assistance, of any kind.

God gives us grace. Period.

That’s what I thought.

But as I’ve made an honest examination of my beliefs, as I’ve prayerfully laid down my preconceived notions, and as I’ve come in fear and trembling before the Lord with a fresh kind of reckless abandon I’ve come to a startling new conclusion.

What I thought I knew about grace was wrong.

Grace in the Jesus-Only Church

It’s important to understand, from the get-go, that the Jesus-only, Bible-only movement in Protestantism is really quite new.

When I first learned this I was pretty confounded, but it’s true. It was, principally, the Congregationalist Puritan movement in the United States which created a cultural of the individual Bible-reading Christian. It was this movement, heavily inspired by the highly insular, individualistic American culture, that’s created the kind of churches, and evangelical Christians, that we think of today.

Said a different way, if you believe that a good Christian lives like Christ, reads their Bible, and loves their neighbour your philosophy is a direct result of American Puritan tradition.

Prior to the Congregationalist movement, and in other parts of the Christian world, a different philosophy of what it meant to be a Christian was the dominate narrative and that was one of communal spirituality—we, together as the church, lived out the Christian life. From this perspective, I was no better able to be a good Christian by individually reading my Bible than you would be a world class chess player by exclusively with yourself.

In this historical context it made sense that grace was a community experience. In fact, stretching from the very early beginnings of the Church in the Acts of the Apostles right through to the theology of the Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin was the belief that God’s grace was experienced through the community of the Church. In this, a solidly historical context, grace was given out from God, by man, in a community of believers.

If that shocks your Protestant sensibilities bear with me, because it shocked mine, too.

How God Gives Grace

God certainly gives us grace in a variety of ways, the Scriptures are clear about that, but they are also clear that one way of receiving grace is through the help of our fellow believer. We’re asked, for example, to pray for one another. In the letters of Peter, Paul, and John, for example, these unquestionably Christian sources, the divinely inspired authors ask for the prayers of the communities they’re writing to. Here, God gives grace, through the prayers of fellow believers.

In his epistle, James writes of this same kind of grace, mediated out through man, when he urges believers to “confess your sins to one another and pray for one another so that you may be healed” (5:16). How are we healed? Through the grace of God—which comes through the confessing of our sins and the prayers of our fellow believers. Here, again, God gives us grace through each other.

Are you tracking with me? Because this, to my ears, was a decidedly different perspective than I’d ever heard as a Protestant. But it’s right there, in Scripture, and it seems pretty plain as day.

God Chooses Man to Mediate Grace

Before I say more it’s important to say this, though, that God can give grace any old way He wants to. God is not—heaven forbid—limited by our rather uncreative imaginations. God can give grace however He wants to. My point, however, and the point of much of Christian history and tradition (and the unwavering stance of the Catholic Church) is that through man is the way God has chosen to give us his grace—to work in our lives.

As Bill Nye used to say, consider the following examples of God working, through mankind, in the Old Testament:

- God chose Abraham to father His people.

- God uses Moses to deliver the Ten Commandments.

- God uses prophets to “speak” on His behalf.

- God chose judges to mediate His justice amongst the Jews.

- God chose a king, David, to rule the Jewish nation.

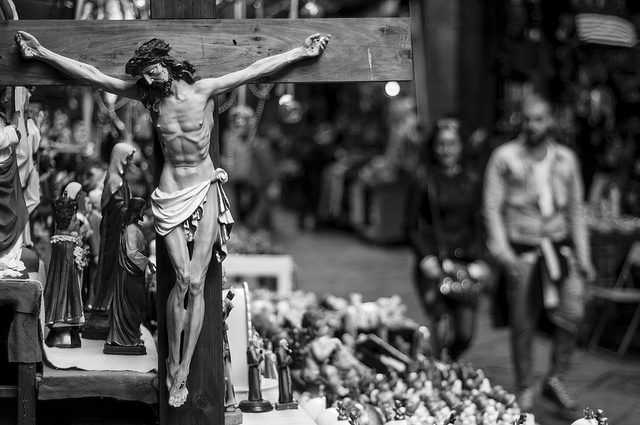

The entire Old Testament system of animal sacrifice, a foreshadowing of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, was mediated by humans—the Jewish priests.

But, you could say, that was the Old Testament. Jesus came and ushered in a New Covenant, in the New Testament, in which He gives grace directly. We’ve already seen, however, that the New Testament is clear in the cases of confession and prayer—that God does work through man to “give out” His grace. And history recommends itself as well—grace through man, in community, was the norm until the Congregationalist movement.

Jesus’s tells his apostles, for example, that “whoever’s sins you forgive, they are forgiven.” The first words of Jesus after appearing in the Upper Room, and offering “peace,” is to give his followers the ability to forgive sins—and mediate the grace of forgiveness. An authority, I should add, that the Catholic Church retains, and traces right back to these very same apostles.

Grace Through Man Does Not Diminish the Cross

A pious Protestant might, rightly so, scoff at the idea of grace being something that man mediates. Despite clear examples in the Old and New Testament it shocking, to our inherited Congregationalist philosophies, to think that anyone other than Jesus gives us grace. But, as I’ve shown, there are crystal clear examples. And history is on our side.

It’s important to affirm, nonetheless, than God working through man doesn’t diminish the cross. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. In fact, God used the cross, and became man, to mediate grace “through man” in the most ultimate way.

Jesus, then, was the prototypical example of God using man to mediate grace.

All of our grace—all of it—ultimately comes through the sacrifice of a man, who was also God.

Still think God doesn’t use man to mediate grace?

It’s difficult to argue otherwise, and theologians for the first 1,500 years of Christian history (and the Catholic Church, to this day) understood it well. God used man throughout the Old Testament to mediate His grace to the Jewish people. He did, on occasion, speak directly to men but this was rare, and in these cases He spoke to this men to then, in turn, mediate His grace to others. Then, theologians agreed, Jesus sets up for us a new example of the same old thing. By becoming human, God again uses “man” to give us grace, and the ultimate example.

Why Grace, Through Man, is Great

It no longer sounds strange to my ears to think of grace being mediating through the means of mankind. This, I understand, seems to be the way that God’s always worked. And continues to work today.

The grace I’ve experienced, through humans, in the Catholic Church has been phenomenal. I can’t even begin to explain to you what it feels like for someone to say, “Your sins are forgiven,” and have the authority, from Christ, to mean it. I can’t begin to explain how much more real that feeling is than the one I can muster up, all alone, praying for God’s grace and forgiveness on my living room couch.

God’s decision, and preference, to work through human kind to give us grace is one of the most wonderful and incredible things He could’ve done. In this way—and this is the way of the Catholic Church, the way of all Christianity for 1,500 years—God’s grace and love and mercy is made tangible to us fickle, fragile humans. What a great gift that is, and what an amazing God.