If we listen carefully, Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” has much to teach us about race in America. And it even gives us hope.

This article is a continuation of my piece “The Problem with Ebony and Ivory.” If you haven’t read that yet, please do. I’ll wait.

Welcome back.

The song proposes the piano as a metaphor for the possibility of racial reconciliation. Just look at all those rows of alternating black and white notes, side-by-side, “living in perfect harmony.”

Harmony?

But have you ever actually played a black and white note on a piano at the same time? The result is a grating dissonance: a half-step, the most ear-burning combination of notes. Learning how to play harmony on the piano requires years of study and practice. Without that hard work, all you get is cacophony: white and black notes clanging against each other, with no resolution of that dissonance in sight.

I propose a better musical metaphor, one which is not based on the simplistic symbol of the piano keyboard, but instead on a complete composition written for it. A piece whose musical structure and historical context both testify to the complexity yet ultimate possibility of racial reconciliation.

Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag

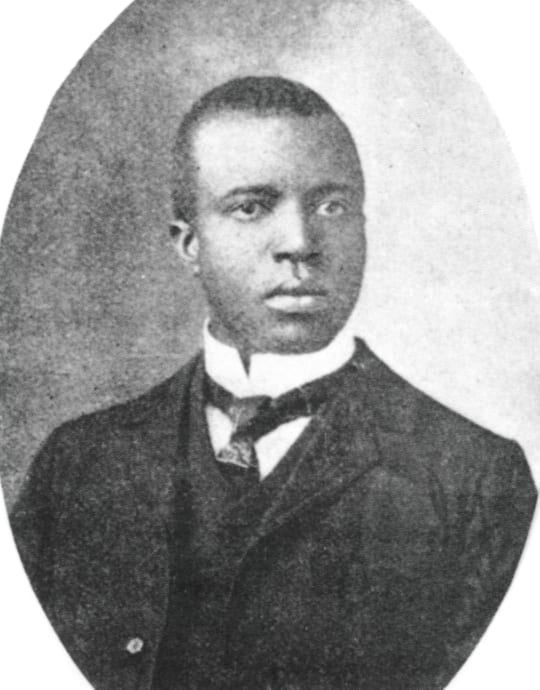

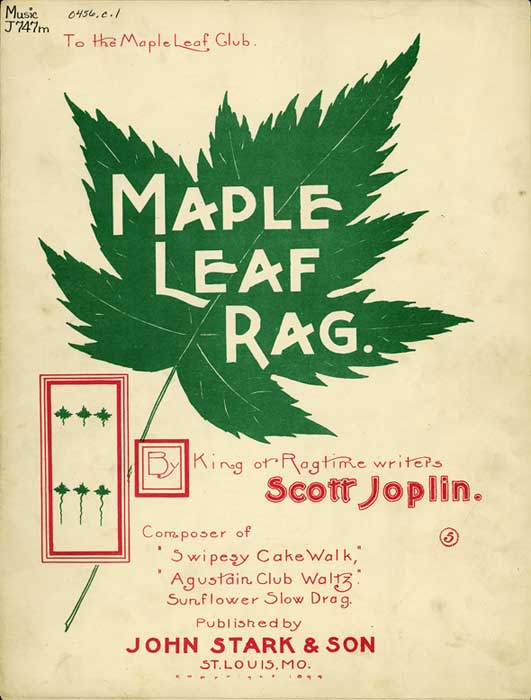

The song I’m talking about is “Maple Leaf Rag.” It’s a ragtime piano piece written by Scott Joplin, the first great African-American composer, in 1899.

Born just after the end of slavery, his is the classic “American Dream” story. As a Black child in Missouri, he had the newfound opportunity to study classical piano with a local teacher. Eventually he started working as a singer and music teacher. A new kind of music was sweeping the Midwest, a combination of Black folk music and Western classical music. He started to write down his own compositions, and the rest is history. The publication of Maple Leaf Rag brought him international fame and riches. Dubbed the “King of Ragtime”, he wrote more piano pieces, two ballets, and an opera before his death in 1917. Though left unfinished that opera was reconstructed and awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music in 1976.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of ragtime in music history. It is one of the main ingredients in jazz and the “classic” blues, both of which were developing around the turn of the century. It also contributed to the transformation of Western classical music in the early 20th century, inspiring composers like Claude Debussy,Igor Stravinsky, and.Aaron Copland.

Syncopation

So what was so special about ragtime? How did it change the history of music? The answer is its rhythm. Specifically, ragtime contributed the fundamental ingredient to all American popular music for the past 100: syncopation. Syncopation – which is a fundamental element of African and African-American folk music – is a type of rhythm that emphasizes “off-beats.” To hear a good example of syncopation, tap your foot to the song “Uptown Funk.” As you listen to the opening bass line, you’ll notice that the 4th “DOH” occurs between the taps of your foot. That’s an example of syncopation:

You can hear syncopation in Maple Leaf Rag in the upper part, the high music played by the right-hand of the pianist. Most of those fast notes are syncopations. Tap your foot to the recording and you will hear (and feel) them.

The March

Joplin and other ragtime composers also incorporated another kind of music that they knew well, a music with origins in the white community: the march. Especially after the Civil War, marches became a mainstream part of white and Black American culture. Americans heard them at parades and at concerts held at the town bandstand. Because their origins in the military, marches became powerful symbols of patriotism and American-ness. They continue to do so today.

So where is the march in Maple Leaf Rag? It’s all over. Most obviously, it’s in the left-hand of the piano. Play the recording again and this time try to listen just to the bass part, starting in the second strain[:048] . There it is: a constant oom-pah-pah, which in a marching band would be played by the tubas and French horns.

To review: the right hand of the piano is highly syncopated, featuring the kinds of rhythms that Scott Joplin learned from the Black folk tradition. The left hand, however, contributes rhythms (and chords) that come from the march.

Now listen to the piece again. Notice that both layers of the music fit together perfectly, playing off each other in surprising and delightful ways, but in doing so neither loses its identity. In fact, what makes ragtime special – what made it so important to the birth of a new kind of American music – is that its whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Neither the right hand nor the left hand is particularly interesting by itself. But, played together, the result is magical. (If you want to hear one of my favorite performances of this piece – one that captures its verve and excitement – click here.)

Interculturalism and the Body of Christ

Now we can finally hear Maple Leaf Rag as a musical metaphor for racial reconciliation. It draws it power from the complex interactions between music with widely different origins and cultural meanings. Neither is eclipsed by the other, and neither dissolves into the other, as in the “melting pot” metaphor for American culture. Instead, this piece is a sonic metaphor of the concept of “interculturalism”, which describes a community in which each culture understands and respects the other. As a Christian, this reminds me of 1 Corinthians 12:

12 For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. 13 For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit… 14 For the body does not consist of one member but of many…. 21 The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.” … 26 If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together.27 Now you are the body of Christ and individually members of it.

We can hear “Maple Leaf Rag” as a sonic example of the Body of Christ, with each layer being one member: an integral part that cannot be ignored or jettisoned, and without which the piece loses its power. Of course, there are problems with Paul’s message, especially regarding slavery, which he seemed to at least tolerate. But his message was – and is – still radical: the Good News of Jesus was available to all, and membership in the body of believers was open to anyone, no matter how society valued them. It is this message that sustained the Black church, that inspired the Abolitionists, and continues to inspire those in many churches today.

Hopes and Challenges

Scott Joplin was born into a new America that had just discarded the chains of slavery. It was a world full of promise, full of hope for the future. His career and his music remind us of the possibility that America might live up to its ideals.

But as we know, by 1899 Reconstruction was a memory, Jim Crow was on the loose, and African-Americans were about to flee the South in record numbers. But as they did, they brought their music to the ears of white Americans in the North, to the urban centers of music publishing and recording. In so doing, their music transformed American society, leading to the development of jazz, gospel, rock’n’roll, hip-hop, and every other kind of American popular music.

Thus, Maple Leaf Rag reflects the complex historical context out of which it emerges. On the one hand, it is an extraordinary musical example of interculturalism, one that testifies to the transformation of America after the Civil War. Yet at the same time it also reminds us just how far we are from that world today. We can hear it as a tragic reminder of a promise not yet fulfilled.

In the gospels, Jesus often commands us to listen: to his words, to God, to the Spirit, and to each other. And then he has a simple directive: “Go and do likewise.” As Christians, we need to hear Maple Leaf Rag ultimately as a call to action. Let’s let it be a sonic reminder that being a Christian means not just holding onto hope, but also working for justice.