A full-voiced choir. Trumpets, cymbals, and drums. THIS is the kind of music best suited for the Almighty King.

Except…is it?

Psalm 19 begins:

The heavens are telling the glory of God; and the wonders of his work display the firmament.

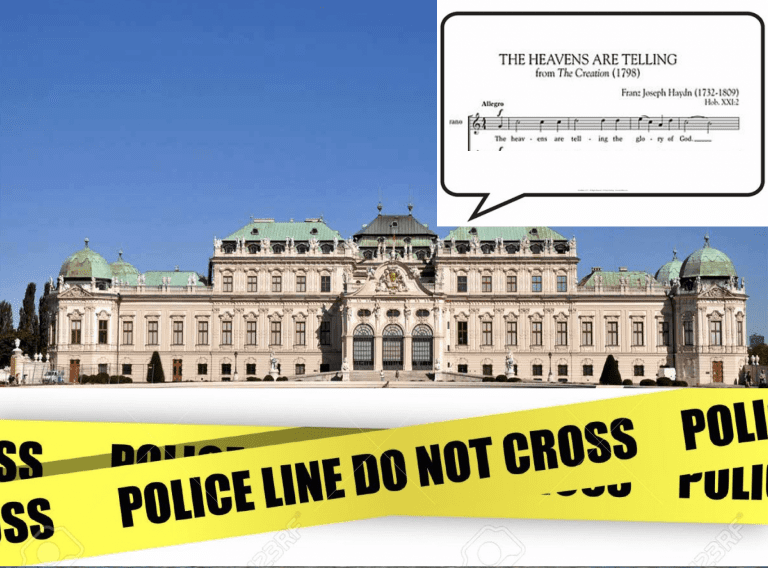

The most famous musical setting of these lines appears in Franz Josef Haydn’s oratorio “The Creation” from 1798. It’s a blazing and glorious piece that has become a standard church anthem: Take a listen:

The Bible often describes God as an all-powerful, almighty King: the kind of God who is worthy of an eternal choir of angels singing with the volume cranked to 11. And with that in mind, you might think Psalm 19 is a prime example. Its description goes beyond the comparatively wimpy sonic abilities of the human orchestra, and instead describes the praise offered by the heavens themselves.

Power in Silence?

But what’s interesting here is that Haydn only sets to music the first two verses. Now, carefully selecting verses is something that we composers are allowed to do in order to make our messages more powerful. Heck, preachers do it all the time, too! But in this case, Haydn’s choice to only set the first two verses allows him to ignore the actual meaning of the psalm. Here’s how it continues:

3 They have no speech, they use no words;

no sound is heard from them.

4 Yet their voice goes out into all the earth,

their words to the ends of the world.

These next lines tell us exactly what the praise of a trillion stars, galaxies, supernovas, and black holes sounds like:

Silence.

And yet…their voices and their words suffuse the entire universe.

Now, the ancient Hebrews knew that the heavens made a lot of noise. They knew about thunder, lightning, tempests, and hailstorms. And they also knew that the God who created all of those apocalyptic natural phenomena was an all-powerful God. But this psalm reveals that this cosmic silence reveals God’s glory – and power – just as well. In fact – maybe it does so in ways that tell us more about God’s distinctive character. Recall the famous story of Elijah:

And behold, the Lord passed by, and a great and strong wind tore into the mountains and broke the rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake; 12 and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire [a]a still small voice. -1 Kings 19: 11-12. (NKJV)

Power in Weakness?

Of course, as modern people who have shown our power (not to mention our hubris) by dominating the world that God made for us, we are drawn more powerfully to the heavy metal God than the folk-music God. We live our lives at maximum volume. We channel God’s power through our willingness to transform – not to mention destroy – the natural world.

But let’s not forget that the real power of the Christian message hinges not upon a God of mighty strength, but of weakness: a God who became incarnate as a poor Judean carpenter, a God who turned the other cheek…even at the moment of his death. And, at that moment, he showed what real power is like.

Jesus was the living exemplar of the ways these two kinds of power can co-exist. It’s a paradoxical understanding of God, but not one invented by the New Testament writers. Just look at Isaiah:

Thus says the high and lofty One who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy, “I dwell in the high and holy place and also with the one who has a contrite and humble spirit, to revive the spirit of the humble and to revive the heart of the contrite. -Isaiah 57:15

A Politically Dangerous Composition?

As a modern Christian, Haydn’s setting of Psalm 19 makes me uneasy. It’s not just that it misses the point of the psalm: it’s that it willfully perverts its meaning by ignoring the lines about the holy silence of God’s creation.

Now, Haydn was a genius, and he certainly knew his Bible. So how do we explain this curious “mistake”? The easy answer is that Haydn (and the man who adapted the scripture for this work, Gottfried van Swieten), was simply doing what we all do: grabbing a line or two of Scripture (out of context, usually) in order to support what we already believe.

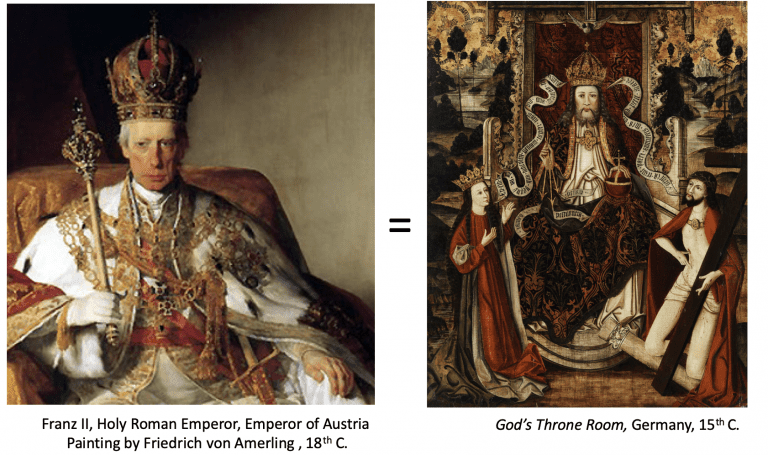

I’m not saying that Haydn is doing anything wrong. By the time has began composing this work, European civilization had been depicting God as a king for over a millennium. For example, check out these two paintings:

In the same way as these artists, Haydn (and all other composers) had for years developed a set of musical symbols that they used when they wanted to depict God. And these are the same sounds they used in music dedicated to the king. They used trumpets and timpani to show both God’s majesty and the king’s military might. They even used the same handful of keys, like C major and D major, because of their particularly “bright” sound.

This is not an accident. It was very common for a king to commission a composer to write a work in celebration of an event – like a coronation or a military battle – and this work was usually sacred: a setting of a Biblical story (like Zadok’s coronation of King Solomon) or a prayer (like the Te Deum Laudamus). These sacred works, celebrating a secular occasion, used sound and circumstance to fuse the all-powerful heavenly King and the all-powerful earthly king into one entity.

So it makes sense for Haydn to depict an almighty God as an almighty king, especially in the Genesis story. In the beginning, the God of power and might bends creation to his will, showing his power by bringing order out of chaos. The political resonance is obvious. Like God, the earthly king brings order to an unruly society, transforming an unwashed mob of serfs into a political entity: a state out of a people. And the only way a state works is if everyone knows their place.

On the day of the premiere of The Creation, the common people certainly knew their place: outside the concert hall, not in it. That’s because the first performance, sponsored by wealthy noblemen, was invite-only. Noblemen, merchants, and other prominent citizens of Vienna were the only ones allowed in.

What they heard, of course, was a glorious, 2-hour musical and theological confirmation of what they already believed: that God was an all-powerful king, and that they were His chosen people. Fight the power? No chance – not when the king has both God AND Joseph Haydn on his side.

A Modern Response

So what do we modern people do with “The Heavens Are Telling?” Do we “cancel” it? Demand that it be performed only when preceded by an ideological trigger warning – or, at least, at a quieter volume level?

Well, no. We need to keep listening to it, but to do so with a critical ear. If we just ignore it and forget it, we are doomed to repeat the sins of our forebears: allowing secular leaders attempt to co-opt God – and culture – in order to confirm and maintain their power.

As a composer, however, I have the opportunity to do something else as well: provide my own musical interpretation of this psalm. And that’s what I did in 2007, when I took this psalm and set it to my own music.

But I didn’t choose to write it for a mammoth choir and orchestra. Instead, I chose a single male voice with piano accompaniment, making it into a piece that could be performed in an intimate setting like a recital hall, or even a house concert.

My setting is quiet and intimate – a simple song that tries to evoke a sense of humility. As I was writing it, I imagined myself as King David, sitting alone, at night, on a hilltop far from the palace. I imagined him doing what we all do sometimes: gazing into the night sky, trying to conceive of the God who made the universe.

That made me feel small. And quiet. And thankful. It made me sense the presence of the Creator of the universe.

And a still, small voice was enough. Take a listen here: