Editor’s Note: This article is part of Altmuslim’s Hajj 2015 series, featuring articles and reflections upon Hajj, the holy days of Dhul Hijjah and Eid ul Adha.

By May Alhassen and Fatima Ashraf

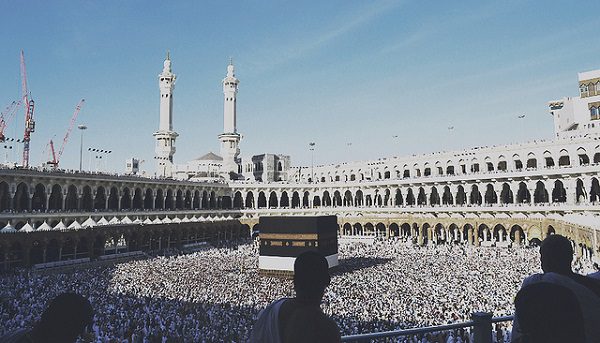

More than two million Muslims gather in Mecca, Saudi Arabia each year to perform Hajj. Hajj is a sacred journey and series of religious rituals that honor Oneness, pay homage to the lives of prophetic figures like Abraham and Hagar and symbolize a unified Ummah, or community of people.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said, “The Muslim Ummah is like one body. If the eye is in pain then the whole body is in pain and if the head in in pain then the whole body is in pain.” Through this hadith, the Prophet explained that Oneness extends to the Ummah. In Quran and Sunnah we find countless examples of the importance of taking care of each other and assertions that our collective well-being is as important as our individual selves.

In fact, much of Hajj is about how we treat one another. Before beginning the journey, we must enter into a physical and mental state of ihram –letting go of anger, exercising patience and shedding any connection to worldly materialism and hierarchies (in the special clothes we wear).

In today’s world, our body, our Ummah, is sick. Warfare, political unrest, oppression of all kinds is making human suffering insufferable. Many of us are at a lost for what to do – we donate money, we write to politicians, we take in refugee families, start and support aid organizations and, of course, we pray. But the long-term global situation of Muslims remains the same or is getting worse.

In today’s world, it might be time to think more critically, to take more drastic measures, and to put real pressure on world leaders in order to heal our Ummah. Islam is not only a religion of peace, it is a religion of justice and equality. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) is one of history’s greatest political activists. Some of his first fights were against the discrimination of women, children, the poor and the illiterate.

Like all the prophets before him, he placed value on humans not because of their material wealth or social status but on their commitment to God and humankind. As our Ummah’s situation worsens, it might be time to reexamine our religious vs. moral obligations.

What Has the Hajj Become?

When someone is in pain or is sick, God changes their religious obligations to prioritize healing over ritual. The potential burdens of Hajj, fasting, and even prayer are lifted to fit the circumstances until the strain on the body is alleviated. As mentioned, we are one Ummah, and when one of us suffers, we all suffer. Not only do our circumstances today warrant prioritization of healing over ritual, it may be that our Hajj ritual is contributing to the pain.

In recent years, the financial burden of completing Hajj has grown exponentially to a minimum of approximately $6,000 (CFA 2.2M; Rs 30,000; RM 19,000; 5,000 euro). Some spend upwards of $20,000 on the trip, paying for the ever increasing numbers of luxury hotel suites and first class, air conditioned travel between cities. Hajj is expected to bring almost $20 billion of revenue for the Saudi Arabian government, second only to the country’s revenue from oil.

Many have argued that Hajj has transformed from its original purpose and that it is no longer a pilgrimage where Muslims from all walks of life come side by side to worship. Rather, it’s a tour package where the wealthy get “Ka’ba-view” luxury hotel suites and air conditioned tents within walking distance of holy ritual sites and the poor are denied visas, left without accommodations (Saudi requires using travel agencies) and are hidden from the view of those paying top dollar for this fifth pillar of Islam.

Others have argued that Saudi’s expansion of the holy mosque and development of real estate in Mecca are necessary to accommodate the growing Muslim population – except that the accommodations are displacing people who lived in those areas and are only affordable to and accessible by a small percentage of the global Muslim population.

Another cost of expansion and development is the destruction of historic Muslim sites and replacing them with fancy shops and restaurants; none of which is consistent with the true nature and intention of Hajj. This week’s deadly crane collapse is another example of how Saudi’s concerns with profits supersede concern for people, and how our continued flocking to the mosque justifies its expansion, which led to deaths of innocent people.

Custodians of the Mosque but Not of Muslims

Saudi Arabia often touts its role as “custodians” of the holy mosques, but rarely does it expound on its role in and silence around the degeneration of the Muslim world and the pain and suffering of the Ummah. Worse, those of us who are living in privileged, conflict-free worlds often fail to examine our own role in Saudi’s complicity.

Are we questioning them? Are we pressuring them? Are we considering their and our own hand in the suffering of Muslims? Or are we staying quiet because, among other things, we want to be able to complete our Hajj?

In recent months, the Saudi-led war in Yemen has left 21 out of 26 million Yemenis in need of humanitarian aid. This is over 80 percent of Yemen’s population. Hundreds of children have been killed and thousands are at risk of death by starvation. Besides using weapons provided by the United States (and perpetrating several attacks during the holy month of Ramadan), Saudi is instituting a de facto blockade preventing food and medicine from entering the country. There are also reports of Saudi rejecting Yemeni Hajj visa applications.

Yet, the world is silent to Yemen’s suffering and political isolation.

The refugee crisis however is causing a global uproar. Developed nations around the world are debating the positives and negatives of taking in almost one million refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, sub-Saharan Africa and other regions as a result of wars and political unrest. This map went viral last week showing the gulf states’ woefully inadequate response to the Syrian (and other) refugee crises, while and this article argues that the 100,000 air conditioned Mina tents that are only used five days out of each year could be repurposed as refugee housing during this desperate time.

Saudi claims otherwise, citing that the country has taken 2.5 million Syrian refugees since 2011. However, the majority of these refugees require visas, many become migrant workers, only to suffer human rights violations (more on that later). In another defensive move, Saudi announced its plans to build 200 mosques in Germany where 20,000 Syrian refugees have resettled as of last weekend.

Inside Saudi Arabia, women, migrant workers, and poor people are the targets of consistent human rights violations. There are more than nine million migrant workers in Saudi. Countless reports of abuse, exploitation and forced labor go without investigation. The sponsorship system requires workers to receive written consent from their employers to change jobs or even leave the country.

Employers are known to confiscate passports and withhold wages. Additionally, Saudi authorities arrest and deport foreign nationals, especially from war-torn and poverty-stricken nations including Ethiopia (160,000 workers deported) and Yemen (500,000 workers deported). Twenty-five percent of Saudi nationals live on less than $530 a month and the royal family hides the country’s poverty problem, imprisoning bloggers, activists, and citizens who seek to reveal the country’s corruption.

Saudi’s obsession with political and religious “dissidents” also results in arrests (like Hamza Kashgari, poet and blogger), imprisonment and torture of adults and children for things including “breaking allegiance with the ruler” and “trying to distort the reputation of the kingdom.” Saudi’s open and belligerent hatred of Shias and labeling of the minority group as infidels and idolaters has resulted in exacerbated divisions between Sunnis and Shias across the Muslim world.

In a world where capitalism reins supreme, where profits are always over people, and where lust for money has humans severely mistreating other humans, one effective way to pressure any powerful, tyrannical, and oppressive government is with strategic boycott, divestment, and sanctions.

The world has seen the power of this strategy in the ending of apartheid South Africa. In the case of Saudi Arabia, a strong message of opposition can be sent by refusing to participate in its economy, which we suggest includes participation in Hajj.

Should We Still Do Our (Five-Star) Hajj Pilgrimage?

This is obviously a very sensitive topic. Hajj is a pillar of Islam. It’s an obligation on those who are physically and financially able. It is an ancient, mandated religious rite. But is modern day Hajj truly fulfilling the tenants of our faith? Is our body – our Ummah – sick enough that the obligation of Hajj is second to our obligation to heal?

Is it time to pressure the custodians of the mosque to question whether stewardship means hoarding wealth, committing labor rights violations, displacing people, destroying Islamic history and giving preferential treatment to rich over poor? Is our participation in this increasingly grandiose, expensive, inequitable journey helping or hurting our fellow Muslims?

These are especially important questions for the privileged among us who make multiple pilgrimages – why continue when the obligation is once in your life while others, often the poor and the oppressed, are prevented by from going simply because of who they are?

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) signed the Treaty of Hudaibiyah in the year 628/6AH that included a provision where Muslims would not participate in the Hajj that year. The Prophet felt the essence of the treaty – a 10-year truce between Mecca and Medina – was more important than the fulfillment of the annual religious rite, no matter how emotionally attached the Muslims were to completing it. This set a precedent – Hajj can be delayed for the purposes of political persuasion. In fact, Saudi’s action of denying visas for people from certain countries is a modern day example of politicizing Hajj.

One of the most beautiful things about Islam is its commitment to social justice and the Prophet Muhammad’s legacy of political activism for the sake of equality. In Islam, our treatment of other people mirrors how we treat God, and in turn how God will treat us. Allah has said repeatedly said that worship is not for Him, it is for ourselves.

As Muslims, it is our duty to fight against tyranny and oppression, to uplift oppressed people and to not contribute to their oppression. As the Prophet Muhammed exemplified, we can and should use the tools at our disposal.

As pilgrims around the world prepare to make the journey in a few days, they reach out to their friends and family seeking forgiveness for any wrongdoing in order to purify themselves before Hajj. Perhaps Hajjis – especially those privileged to make multiple journeys, those who come from safe lands, and those who have the money to go in the first place – need to seek forgiveness from the millions of refugees who are fleeing war and are desperately seeking shelter which many in the Muslim Ummah will not give them.

And perhaps Hajjis of 2016 should think twice before spending thousands and thousands of dollars on a five-star ritual supporting Saudi extravagance and make a strong statement to this regime that needs to be held accountable.

May Alhassen is a University of Southern California (USC) Provost Ph.D. Fellow in American Studies and Ethnicity, co-editor of Demanding Dignity: Young Voices from the Front Lines of the Arab Revolutions, (White Cloud Press), co-founder of Occidental College’s Social Justice Institute, and a freelance journalist.

Fatima Ashraf is with the Open Society Foundations in New York City. She focuses on grant making strategies and priorities in the areas of criminal justice, democratic transparency, racial justice, and economic equality. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two sons and is committed to raising children with an anti-racist, anti-oppressive, pro-human world view.