This may be part of a series of posts dealing with the Buddhist relationship with French Existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre. My last post on him was “Life: Existential Reflections (solipsistic brooding?)“, and an earlier one, “Buddhism: learning via enigma” introduced a great book that I’ll be reading over the next couple months. Today I want to interrogate Sartre’s notion of selfhood (as well as I know it) and see how it fits with the Buddhist concept of anatta (not-self). For a quick primer on anatta/anatman, see this old post of mine: Philosophy: “Self, where art thou?”

Your facticity is, as the term suggests, all the facts about you: your height, weight, hair color, etc. As well as the sum total of your past facts: where you graduated high school, what your mother’s maiden name is, who you first kissed, and so on.

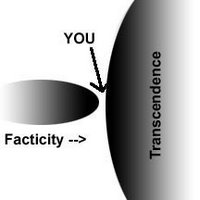

Your facticity is, as the term suggests, all the facts about you: your height, weight, hair color, etc. As well as the sum total of your past facts: where you graduated high school, what your mother’s maiden name is, who you first kissed, and so on.Your Transcendence is the world of possibilities ahead of you, everything you could be or do. Usually the near possibilities seem fairly concrete (going to bed soon if it’s 2am, getting a degree soon if I keep studying, getting a real kiss if I’m good in the next few weeks).

What is your true self? Are you your facticity? Are you your transcendence? No. You are separate from both. And what separates you? Nothingness. Think about facticity. A rock has facticity. It has its own history of facts. As do all inanimate objects. Surely you are not merely your facticity, your history. And your transcendence? In my realm of possibilities is ‘amateur ballet dancer’, right? It is, after all, possible. Professional would be another matter, but my realm of possibilities is enormous. Even very seriously contemplating my future I wonder about more school (England, Canada, USA?), the health of my parents and relationship with my siblings (they could need me at any time), jobs, relationships, and so on. The future is in no legitimate way determined, it is quite open.

This takes us to the key argument (or realization) of Sartre that we inevitably yet always wrongly identify ourselves with either our facticity or our transcendence! Like damned fools we say “I AM a Buddhist”, “I AM an American” to identify with our facticity, or “I AM a philosopher” or “I AM a family man” to identify with our transcendence. We do this, we take on labels. And then we act them out. I am acting the part of the Buddhist-Philosopher. If I try too hard, it becomes terribly obvious to you. What is worse is that if my labeling (my objectification) of myself is not reinforced by others, then I will break down. Our acting, that is, our putting a label on ourselves and then trying to act as one with that label would act, is what Sartre calls Bad Faith.

2 graphic examples:

Sartre gives two graphic examples exemplifying our existence between facticity and transcendence. The first is Vertigo (p.66-69). Imagine standing at the ledge of a tall building, looking over. There is no wind, no one around to push you. You feel dizzy, drawn downward: vertigo. Why? Why shouldn’t this be just like looking down at your feet if you were standing down to the sidewalk below. Your fear arises because you see, ever so faintly, yourself, falling by your own choice to the sidewalk below. You fear the possibility which lies directly before you. The vertigo is actually “anguish in the face of the future.”

The second is The Gambler (p.69-70). This person is wasting his life away in gambling, his children are suffering, he knows he must stop. So one day he decides to stop. He firmly commits to it, he will not gamble any more. But then, soon after that, he passes by a casino. He is drawn toward it. He knows that he has decided to stop, but now that decision has no real power over him – he is not his past as he wishes he were. The possibility to gamble again will forever haunt him. The possibility to undo his decision is what Sartre calls “anguish in the face of the past.” He fears the past, himself as an addicted gambler, overcoming him.

* page numbers here are from “Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology” (1943)

So You are that space between facticity and transcendence, the space which, paradoxically, binds them together. Your history is always there, pushing you forward. Your future is always there as well, an invisible force drawing you forward.

The problem (or at least where Sartre disagrees with Buddhists) is that Sartre seems to deny that we can truthfully realize this fact. Again, we always (wrongly) identify with one side or the other. But there are two notable exceptions to this pessimism over our human condition. I’d like to expound upon both of these in future posts, but for now let me just state them for your consideration:

First, in “The Transcendence of the Ego” (1937, one of Sartre’s earliest works), he comments, “A reflective apprehension of spontaneous consciousness as non-personal spontaneity would have to be accomplished without any antecedent motivation. This is always possible in principle, but remains very improbable or, at least, extremely rare in our human condition.” [his italics] (p.92)

Then, in “Being and Nothingness” he places in a footnote at the very end of his section on Bad Faith, “If it is indifferent whether one is in good or in bad faith, because bad faith reapprehends good faith and slides to the very origin of the project of good faith, that does not mean that we cannot radically escape bad faith. But this supposes a self-recovery of being which was previously currupted. This self-recovery we shall call authenticity, the description of which has no place here.” (p.116)

So, in the first case, Sartre seems to leave open, even if only a tiny bit, our possibility of apprehending our ‘non-personal,’ ‘spontaneous consciousness’. Sounds very much like an opening for a discussion of meditation, dhyanas, and truly living in the moment. And in the second case he contradicts much of his previous discussion on the apparent inevitability of bad faith. He opens the possibility for authenticity (I am told that this notion of authenticity is nothing like that used by Heidegger), or a recovery of that which has been corrupted. It could sound something like this:

From the Mahaparinirvana Sutra: “The atman is the Tathagatagarbha. All beings possess a Buddha Nature: this is what the atman is. This atman, from the start, is always covered by innumerable passions (klesha): this is why beings are unable to see it.” (borrowed from Tom at Blogmandu, who grabbed it at The Zennist)

atman=true, eternal Self.

Tathagatagarbha= ‘womb’ of the ‘thus-come/gone-one’ 0r Buddha = Buddha Nature.

So it seems, at this point at least, that Sartre at least for moment held a nugget of very profound wisdom. Yet his work focuses ad nausium on the inadequacies of the common man rather than our most brilliant achievements, the lies we tell ourselves rather than our moments of truth, and the conflict of life instead of the beauty.

In short, he sees well the first two noble truths but lacks a sense that a third and fourth might be out there.

(note, this was mildly updated 4/11/2014)