I preached my first sermon as teaching pastor at Keller Park Church on January 1, 2017. Preaching that day on Genesis 1-2, I concluded:

When society marginalizes and degrades humans made in the image of God, the church must step up and speak God’s word of truth: You bear the image and likeness of God, and you are very good to God and to us. Affirming the fundamental worth and dignity of each human being we encounter as one who bears the image of God does not erase all our differences, solve all of society’s problems, or gloss over the reality of sin in the world. Rather, it is a simple acknowledgment of what God is up to in the world and a first step for us as a church to join with God in that work.

Nineteen days later Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th president of the United States. Since my pastorate has been roughly coterminous with the current administration, I’ve had ample opportunity to reflect on how to speak God’s word of truth within a society that routinely marginalizes and degrades humans made in the image of God. And I’ve come to realize that it isn’t enough to not be racist or sexist or homophobic or xenophobic. Instead, affirming the worth and dignity of each human made in the image of God requires being actively committed to and engaged in the work of anti-oppression in all of its forms.

This is a daunting realization for an educated, middle-class, married, white male pastor from the Midwest to take in, and it’s required me to do some catch-up reading that didn’t make it into my seminary or grad school syllabi. Here are ten works I’ve read or am reading this year to educate myself on becoming an anti-oppression pastor (in roughly chronological order of reading):

1. Falling Free: Rescued from the Life I Always Wanted, by Shannan Martin.

This book was probably the biggest surprise of the year. I expected a story about the joys, merits, and challenges of downsizing and simplifying life in order to follow Jesus more faithfully. What I wasn’t expecting was a prophetic call to white Christians not to divest of their power but to use their power in anti-oppression work for the sake of, and in solidarity with, the marginalized. In the case of Shannan and her husband, Cory, who’s now a prison chaplain at the Elkhart Jail a couple miles from my office at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, this meant expressing radical hospitality to and solidarity with the incarcerated and those otherwise entangled in an unjust justice system.

2. Fire by Night: Finding God in the Pages of the Old Testament, by Melissa Florer-Bixler.

This book is about one Mennonite pastor’s encounter with the God of Israel as revealed in the Old Testament. And the God she encounters there is a God who fights on behalf of the oppressed. Reflecting on the God revealed in the infamous story of Sodom and Gomorrah, for example, Florer-Bixler writes:

Genesis 18–19 is a case study in oppressive systems, a narrative that invites us to consider a violence so pervasive, so destructive for the people who are caught up in it, that it takes a miraculous and devastating intervention from God to undo it. In this way, I’ve found that the story of Sodom and Gomorrah reorients my notions of justice and compassion. It’s a story that draws me into a longing for both God’s fiery justice and God’s miraculous redemption.

Elsewhere, writing on the Amalekites, Florer-Bixler writes: “Enemies are real. There are destructive forces of violence that haunt the lives of the vulnerable. We need a God who names evil, who is on the side of the oppressed and forgotten.” As I try to engage in anti-oppression work with theological integrity, books like Fire by Night are essential. (In my more ambitious blogging days, I started but never finished a series on Fire by Night; here are some further reflections on chapters 1-4.)

3. Homeland Insecurity: A Hip Hop Missiology for the Post–Civil Rights Context, by Daniel White Hodge.

I’m in an ongoing process of undoing my own assumptions about what it means to do ministry in an urban context, and Daniel White Hodge has been instrumental in that undoing. I first heard him give a fiery address at the CCDA conference last fall and immediately bought his book. Hodge writes as a missiologist of North American urban ministries, and he engages their implicit colonialist, white supremacist assumptions head on. In contrast, he argues for a hip-hop theology to engage the church in the wild, drawing on artists like Tupac and Kendrick Lamar. I’m still processing this book.

4. Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores, by Dominique DuBois Gilliard.

This year I’ve been preaching through the book of Acts, and I’ve been struck by how frequently the early disciples wound up in jail. Yet, I don’t think I can recall ever hearing a sermon specifically on the mass incarceration system in the United States. So when it came time to preach on Acts 16:25-40, where Luke writes that “the prison was shaken to its foundations,” as God broke Paul and his companions out, I decided to preach on mass incarceration myself. And to prepare, there was no better book to read that Rethinking Incarceration. Gilliard not only explains the five major pipelines to prison but also ends with a call for Christians to join in the work of dismantling mass incarceration. (If you want to get a taste of his work, Missio Alliance is offering a free webinar with Gilliard on September 24, hosted by Shannan Martin. Small world!)

5. The 1619 Project, by New York Times Magazine.

The 1619 Project describes itself this way:

The 1619 Project is a major initiative from The New York Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery. It aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.

When I first heard of this groundbreaking project, I ran to the AMBS library to see if they had a copy. Fortunately, they hadn’t thrown out the issue of The New York Times that it came in, so the library was able to retrieve and catalog it, and I was the first to check it out. This project is as breathtaking in scope as it is devastating in its analysis, which is why many white Christians have either avoided it or outright rejected its claims. But both of these approaches are a mistake. In order to participate in the work of anti-oppression, we must first know the history and root causes of that oppression. The 1619 Project is the place to start for that history and analysis.

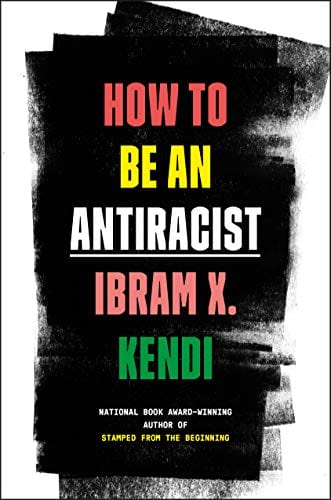

6. How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi.

6. How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi.

The 1619 Project may be the place to start for an analysis of racism and its effects in the United States, but How to Be an Antiracist is the go-to book for getting involved in undoing racism. For Kendi, there is no such thing as being nonracist. Everyone makes decisions and supports policies every day that are either racist or antiracist. Indeed, most of us support some things that are racist and other things that are antiracist. To be antiracist, then, is to recognize racist policies and reject them and to recognize antiracist policies and advocate for them. If it sounds simple, it’s not; and Kendi shares his own ongoing journey toward becoming an antiracist, which he invites the reader to join.

7. The God Who Sees: Immigrants, the Bible, and the Journey to Belong, by Karen Gonzalez.

In an age of travel bans, border walls, child detention facilities, crackdowns on refugees and asylum-seekers, and anti-immigrant and xenophobic rhetoric, it’s helpful to be reminded that the God of the Bible is a God who sees and welcomes the immigrant. Gonzalez, whose family immigrated to the United States from Guatemala when she was a child, integrates reflections on her own experiences as an immigrant with reflections on immigration throughout the Bible—from Abraham to Naomi and Ruth to the Holy Family. And she concludes with concrete ways Christians (and others) can get involved in supporting their immigrant neighbors.

8. I Was Hungry: Cultivating Common Ground to End an American Crisis, by Jeremy K. Everett.

My copastor, Carrie, often says that we can’t tell people that Jesus can fill them spiritually if their stomachs are literally empty. And yet, according to Everett, “One in eight Americans struggles with hunger, and more than thirteen million children live in food insecure homes.” Everett doesn’t believe this should be the case, and he founded the Texas Hunger Initiative to do something about it. I Was Hungry tells the story of THI’s work and calls others, Christian and otherwise, to join in the fight to end hunger. (Since Jeremy is an old friend of mine from when I lived in Waco, I was able to sit down with him for an interview about his work that can be read in three parts: here, here, and here.)

9. “Sexual Violence: Christian Theological Legacies and Responsibilities,” by Hilary Jerome Scarsella and Stephanie Krehbiel.

This is the one academic article I’m including here, and it’s behind a paywall at that, but I include it in this list because I was blown away by the clarity and scope of this short introductory article on the numerous ways in which Christian theology can be used to reinforce systems of sexual violence. And this issue intersects with so many other issues related to anti-oppression work. As the authors write, “Sexual violence is perpetrated disproportionately against those whose perceived worth is historically precarious: women, people of color, LGBTQIA+ people, people with disabilities, people who are incarcerated, detained, undocumented, or without a home.” After clarifying the ways in which Christian theology can be complicit in systems of sexual violence and describing how scholars and practitioners (including pastors!) can become trauma informed, the authors conclude:

It is our hope that scholars and practitioners who work at the intersection of Christianity and sexual violence will take these responsibilities to heart. Equipped with a robust understanding of what sexual violence is, the ability to analyze Christianity’s complicity, and resources for producing new insight that is trauma aware, such scholars and practitioners will be well positioned to craft projects of critical inquiry and community practice that make these responsibilities alive in the church and in the academy, and in so doing, work toward a world that more effectively resists sexual violence and empowers survivors.

10. Trouble I’ve Seen: Changing the Way the Church Views Racism, by Drew Hart.

This is the book currently on my nightstand, but if I were wiser, I would have read it before becoming a pastor. (It was published in 2016 but is hauntingly prescient.) As with Kendi, Hart argues that racism isn’t so much about “KKK-like behavior” as it is about “white supremacy—a superiority complex and the practice of racial dominance fueled by racial ideology” that includes “larger racialized patterns of society that shape individuals’ ideologies and habits” and “the ways that young white people in the twenty-first century continue to make daily choices that advantage them, structurally and systematically, over people who are not white.” In other words, as Kendi also argues, racism isn’t as much about hatred as it is about power. But unlike Kendi, Hart writes as a confessional Christian theologian (in the Anabaptist tradition no less), and so he offers as a “revolutionary alternative” to the dominant culture “counterintuitive solidarity in the way of Jesus.” According to Hart, the church as “a people in which the reign of God is visibly manifested” can begin to embody “a communal life capable of subverting white supremacy both internally, in our churches, and externally, in our neighborhoods and around the globe.”

Bonus 1. Acts, Belief: A Theological Commentary on the Bible, by Willie James Jennings.

I mentioned above that I’ve been preaching through the book of Acts this year, but that’s not entirely true. I started preaching through Acts last year, took a break from Advent through Pentecost, and then resumed preaching on Acts this year following Pentecost. Throughout this extended study of Acts, Willie James Jennings’s theological commentary has been a constant companion. Jennings makes explicit the connections between the early church and the church of today by describing how the Holy Spirit ignited a revolution that disrupts every oppressive system and breaks down every barrier to communion among God’s people.

Bonus 2. “Originating Sins” fall 2019 issue of Vision, guest edited by Malinda Berry.

This is still in the works, but as the managing editor of the journal, I get to read all the articles in advance, and I can confidently say that this issue will be a must-read. Berry understands the phrase “originating sins” as “a way of thinking theologically about the roots and foundations of the institutions that are woven into the fabric of North American life.” For this issue, then, the primary focus is the Doctrine of Discovery, which Berry believes is “the originating sin of Western Christianity.” The issue will describe the Doctrine of Discovery and its devastating impact on Indigenous Peoples, but it will also provide resources for Christians to join in the work of dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery. (I’ll be sure to say more about this issue once it’s out. In the meantime, you can check out recent AMBS graduate Peter Anderson’s reflections on his Trail of Death pilgrimage, which will be featured in the issue.)

I’m still learning. What recent works should I add to my reading list?