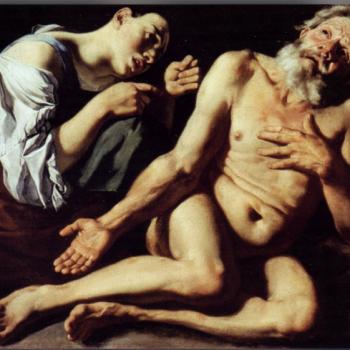

Wikimedia Commons

Martha Graham: the spiritual mystique of a prolific dancer that recreated the pitfall feeling of grief in trembles

I was first introduced to the art of this intensely magnificent dancer, Martha Graham, from a American animated TV series created by Rebecca Sugar (Cartoon Network) called Steven Universe. The animated show, although made for children and young adults, dealt with heavy subjects such as anger, identity, fear, trauma, helplessness and grief. The character of Blue Diamond truly enveloped the latter emotion of total grief. I highly recommend this show, as it has shaped my own views on identity, grief and trauma in ways that were at the time and are, utterly cathartic.

According to this online entry about Blue Diamond:

- Rebecca stated that Blue Diamond’s character design is meant to look “ghostly” to get the feeling of her mourning, and draws a lot of influence from Martha Graham‘s Lamentationballet dance. Her face and hair designs are also inspired by Leiji Matsumoto‘s art, to make her come across as a “strange presence.”

Losing someone you love deeply is a deep cut to your soul. The one person you always believed would be there is gone. It is a finality you cannot measure. You cannot fathom it. It is almost better to deny it or become angry. Why does this sinking pit of despair feel so endless?

That is where the cathartic healing of art and dance come in. Martha Graham, named TIME magazine’s, “Dancer of the Century,” and People magazine’s, “Icons of the Century,” has through her medium, recreated spirituality and emotional themes based on her creative movements.

Spastic movements, tremblings, and falls seem to relive through pivotal moments of grief and trauma, creating a microcosm within her suffocating surroundings, inviting the viewers to feel every labored breath and every break in the movement.

Connecting to others through tragedy

Growing up, Graham had an observant Presbyterian upbringing by her father, and continued this religious outlook her entire life. This religious belief was layered not only in her personal life but in her work, showing several hints of spiritual themes and religious backgrounds.

As I had watched the video of the dance for Lamentation, (Zoltán Kodály’s 1910 Piano Piece, Op. 3, No. 2 as the accompanied piano piece), it to me, had the beginnings of what felt like personal, deep, silent prayer. The prayer of silent grief that drives us to revisit our pain, to revisit our passed on loved ones in order to heal from the deep loss, and to pray to God for our loved ones to be at peace in the afterlife.

Graham described her first performance in 1930: “a solo piece in which I wear a long tube of material to indicate the tragedy that obsesses the body, the ability to stretch inside your own skin, to witness and test the perimeters and boundaries of grief, which is honorable and universal.”

The most telling of how deeply healing Lamentation has helped others in the scope of grief was that after one of Graham’s performances, a woman had gone up to her after watching the dance who had recently lost her child in a car accident she had witnessed. Watching Graham perform Lamentation had helped her grieve. This had a significant impact on her as she realized that “grief was a dignified and valid emotion and that I could yield to it without shame.”