Frances Perkins was having lunch in New York on March 25, 1911, when the sound of fire engines lured her and her companions onto the street to see what was taking place. Perkins – at the time the Executive Secretary of the New York City Consumers League – had been hard at work on industrial reform, advocating better fire protection for factories and a limit to the number of weekly working hours for women and children, among other worker safeguards. But on that March day, Perkins was horrified as she witnessed workers jumping from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory’s windows to escape the flames. In all, 146 workers – mostly women and children – died as a result of the fire. Later, Perkins recalled that witnessing that fire was the day that the “New Deal” was born – a day on which she committed herself to doing everything possible to ensure that such tragedies would never occur again.

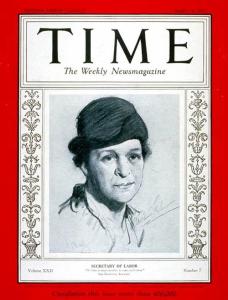

Frances Perkins, the first female US Cabinet member, was appointed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as his Secretary of Labor in 1933 – in a country still shaken from World War I and still mired in the Great Depression. By the time FDR tapped her to serve as Secretary of Labor, Perkins had created an impressive resume of labor achievements, with a reputation that had garnered respect from across the political spectrum.

After graduating from Mount Holyoke College in 1902, Perkins began working with the poor and unemployed. Eventually landing in New York to study childhood malnutrition, she enrolled at Columbia University and earned a Master’s degree in sociology and economics. In New York, Perkins gained skills as an advocate for social reform.

President Theodore Roosevelt recognized her gifts and recommended her to serve as Executive Secretary of New York’s Committee on Safety, a citizen’s committee formed after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire to help prevent similar future tragedies. She served under New York Governor Al Smith on the New York State Industrial Commission and as his labor advisor. When Smith was succeeded by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Perkins became the state’s Industrial Commissioner, overseeing the work of the state’s labor department. While Governor of New York, Franklin Roosevelt committed to unemployment insurance – and Frances Perkins was tasked with making recommendations for its implementation.

After Roosevelt was elected President in 1932, he tapped Perkins to serve on his cabinet as Secretary of Labor. The “New Deal,” which Perkins largely shaped, focused on six priorities to help stimulate recovery from WWI and the Great Depression and to provide safeguards for workers: (1) a minimum wage, providing sufficient income for workers to live on; (2) federal unemployment relief for the 13 million workers who had been left unemployed during the Great Depression – along with public works programs to help reemploy unemployed workers; (3) a forty-hour work week; (4) ending child labor, so that children could attend school and adults could work all available jobs; (5) a workers’ compensation program, for injured workers; and (6) and old-age pension program into which workers and employers would contribute, so that workers could receive benefits at retirement (Social Security). The old-age pension was in clear recognition that the Great Depression had made it harder for older workers to find and secure employment.

Perkins had one other hope for the New Deal – and that was universal health insurance. The health insurance was not included in the package of benefits.

Perkins worked tirelessly to ensure that the New Deal’s provisions would be enacted. By 1935, Roosevelt was signing the Social Security into law, and by 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act was also enacted. Perkins had made good on her promise to help push the New Deal across the finish line and reenergize America’s workforce. Perkins is credited with having said, “I came to work for God, FDR and the millions of forgotten, plain, common workingmen.”

After serving through the entirety of Roosevelt’s administration, Perkins’ remaining years were spent teaching, lecturing and writing – continuing to advocate for the most vulnerable American workers.

Throughout her storied career as a pioneering female professional, Perkins championed improved conditions for American workers, and continued to credit her commitment to underserved workers to her faith and belief in God’s commandment to care for the most vulnerable. From childhood, Perkins had been surrounded by history and legacy that had shaped her understanding of the world. Before her birth, a cousin, Union General Oliver Otis Howard, had become the first head of the Freedmen’s Bureau; Howard would later become one of the founders of Howard University, which was named after him. Family stories such as those of General Otis Howard spurred Perkins’ interest in the plight of workers and the less-visible.

What would Frances Perkins say about the state of the poorest American workers today?

Perkins argued for minimum wages that workers could live on. The current $7.25/hour federal minimum wage has not been increased since 2009 – despite the fact that, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index, one dollar today only buys 70.811% of what it could buy in 2009 (Stated another way, today’s prices are 1.41 times as high as average prices since 2009.).

Perkins advocated bringing an end to child labor. In a tight labor market in which employers need workers, several states are considering laws that loosen child labor restrictions. Arkansas, for example, recently eliminated a requirement for teens under age 16 to apply for permission from the state’s Division of Labor to be employed; the state also eliminated a requirement to verify the age of teens under 16 before they take a job. These changes came amid claims that Tyson Foods and at least one other Arkansas employer have employed young teens – many of them, migrants – to work in third-shift meat packing plants with hazardous chemicals and equipment.

And perhaps before her time, Perkins became an advocate for universal health insurance – to make provisions for Americans to be able to access health coverage and seek medical care. The current employer-based health system, which gained momentum after World War II as employers looked for ways to recruit and retain workers, allows millions of American workers to fall through the proverbial cracks if they work less than a full-time schedule or work for small employers.

The commandment that seems to have fueled Frances Perkins’ commitment to American laborers – God’s commandment to care for the poor widow, the orphan and the foreigner – appears numerous times in scriptures as an inescapable edict. Jesus lived that commandment as an example to us all.

Matthew Desmond raises a significant question for our time in Poverty, by America: What are we doing to divest from poverty? Desmond offers that there are choices well within our means that can make the difference between poverty for our neighbors and a more secure future.

Frances Perkins’ New Deal reminds us that at least once in American history our nation was committed to providing better economic security for our neighbors. We can do that again, if we dedicate ourselves to doing so.