June 18, 1964.

It’s often said that a picture is worth 1,000 words.

So it was that a photo of James Brock, manager of the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida, pouring muriatic acid into the pool where black and white guests were swimming on June 18, 1964 – spoke loudly as Congress wrestled with the passage of a Civil Rights Act. In St. Augustine, where nonviolent protest efforts to desegregate beaches and places of public accommodation had been met with a violent backlash, the swimmers were, no doubt, staging a swim-in. Brock’s action apparently, was more an effort to frighten than to harm the swimmers, as experts claim that a single gallon of muriatic acid diluted in the pool likely could not have harmed the swimmers. But the photo quickly made national news and told a sad story of the bitter fight for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One day after the photo was taken, on June 19, 1964 (Juneteenth, anyone?!), after four months of debate and filibuster, the Senate passed the Act by a vote of 73-27. The House of Representatives had already passed the Act by a vote of 290-130. And, President Lyndon Johnson would sign the Act into law on July 2, 1964.

That such an iconic photo of a motel manager pouring acid into a pool filled with swimmers could arise at that time from St. Augustine, the oldest continuously occupied colonized settlement in the United States, was a story in and of itself. St. Augustine holds a rich history of European, African and Native persons – and its history is tied to Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church. When Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles landed in what is now St. Augustine, Florida in September 1565, he immediately began to discover the potential of this new land, blessed with a healthful climate, fertile soil, and a multitude of natives whose conversion to Catholicism he approached with great zeal. Pedro Menendez arrived at St. Augustine some 50 years after historians credit Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Léon with having been the first European to arrive in the area in 1513; Spain’s King Ferdinand authorized Ponce de Léon to settle this land that he had called, La Florida.

While St. Augustine was visited by Spanish, French and British would-be settlers, it wasn’t until 1565 that Pedro Menendez would actually settle and claim the land for Spain. Control of the area bounced back and forth between Britain and Spain for the next two-and-one-half centuries; ultimately, its control was turned over to the United States in 1821.

The would-be European settlers of the area all apparently arrived with enslaved African persons. According to the City of St. Augustine’s website, during these years of competing colonizers arriving on her shores, St. Augustine also became a home to enslaved black persons who chose freedom in exchange for having declared allegiance to the King of Spain and converted to Catholicism. As such, St. Augustine became a stop on the Underground Railroad, and both freed and enslaved black persons made the area their home.

By the turn of the 20th Century, when Henry Flagler (one of the founders, along with John D. Rockefeller, of Standard Oil Company) made a foray into St. Augustine, he put it on the map as a tourist resort after building opulent hotels to cater to the wealthiest clientele and purchasing what would become the Florida East Coast Railway to allow ease of travel to this resort location. Flagler’s website touts that Flagler is largely responsible for Florida being “the third largest state in the Union with an economy larger than 90% of the world’s nations. Indeed, no individual has had a greater or more lasting impact on a state than Henry Flagler has had in Florida.”

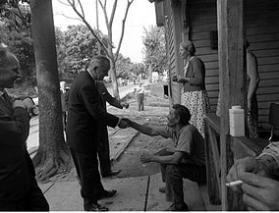

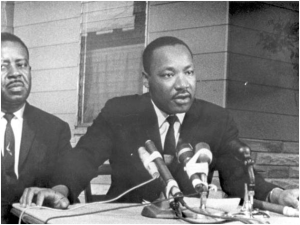

But the month of June invites us to consider a different piece of St. Augustine’s history: St. Augustine would also be known for its pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. By June 1964, as the push to desegregate public accommodations grew more intense, St. Augustine found itself in the eye of the proverbial storm. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to St. Augustine to lead peaceful protesters in restaurant sit-ins and beach swim-ins, in an effort to urge the desegregation of those accommodations in the nation’s oldest city. The peaceful protesters were reportedly met with violent counter-protests, and Dr. King, Ralph Abernathy were among the protesters who were arrested following a sit-in at the Monson Motor Lodge restaurant.

Within days, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would be passed – and signed into law. But the passage of the new law was certainly not the end of the struggle for freedom.

Nearly sixty years after peaceful protesters sought the right to enter beaches, restaurants, pools and other accommodations in St. Augustine, Florida, we commemorate their struggle.

1964 was a long time after the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, respectively in 1865, 1868 and 1870, giving freedom to enslaved persons, making them citizens of the United States to be afforded due process and equal protection under the law, and granting them the right to vote.

1964 seemed like a long time to wait, to have struggled for justice, and have hoped for a day on which all of God’s people would be seen as having been made in God’s image and likeness.

And, picturesque, historic St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest continuously occupied colonized settlement in the United States, a city steeped in religious history, seems an unlikely – or, alternatively perfect – spot to which to draw the nation’s attention to the acceptance and normalization of racism. Its place in history is duly noted and commemorated.