What caused the fire?

When scholar and author Matthew Desmond spoke in Memphis in May 2023 about his latest book, Poverty, by America, he borrowed a line from author Tommy Orange and compared privileged Americans’ attitude toward poverty as that of onlookers watching kids jumping from the windows of a burning building: Everyone is focused on the jumpers, and believes that if only we could stop them from jumping, everything would be okay. No one, Desmond says, is asking about the fire. Similarly, he finds that Americans who are privileged to enjoy a standard of living that well exceeds poverty may ask about the poor, but about not the ways in which any or all of us can help eradicate poverty.

Desmond’s reference to the burning building was very much reminiscent of the story of Frances Perkins, recognized as the woman behind President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Early in her career as an advocate for working-class Americans, Frances Perkins was having lunch in New York in 1911, when she witnessed workers jumping from the windows of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which was engulfed in flames. 146 workers – mostly women and children – died as a result of that tragic factory fire. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire ignited a fire in Perkins, who committed herself to helping American workers.

Put another way, she not only asked about the fire, but what we could do to prevent tragedies like it in the future.

Perkins became the first woman to serve on a U.S. President’s Cabinet, serving President Roosevelt as his Secretary of Labor. She is credited by many as truly being the architect of the New Deal. Following the Great Depression, at a time during which workers struggled to gain footing, Perkins became an advocate for worker protections that we still know today: a minimum wage that was then intended to provide workers sufficient livable income; a forty-hour work week; an end to child labor; public works programs to help put Americans back to work; federal unemployment relief for the 13 million workers unemployed as a result of the Great Depression; a workers’ compensation program, for injured workers; and an old-age pension program into which both workers and employers would contribute, allowing workers to receive benefits at retirement (Social Security). All of the New Deal’s initiatives were envisioned to put Americans back to work, help create a more just working environment for American workers, and rejuvenate a lagging economy. Apart from the New Deal, emergency daycare centers opened for mothers who were making their way into the workforce during WWII, marking the only time in American history that government-subsidized childcare was available for working parents.

The New Deal did succeed in putting some Americans back to work; unemployment decreased, in part because workers had been hired under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to carry out various public works projects from building roads to constructing public buildings. And the economic safety nets (Workers’ Compensation, Social Security) helped workers who had been injured on the job and aging workers immeasurably – and continue to provide support even today. But the New Deal suffered much criticism from both conservatives and liberals: Conservatives argued that it was government overreaching, while liberals argued that it hadn’t gone far enough in supporting Americans who most needed the help.

A War on Poverty?

Fast forward thirty years to President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 State of the Union address, in which he declared an unconditional war on poverty in America. With the Census Bureau reporting the poverty rate stubbornly persisting at nearly 20 percent of the American population, President Johnson signed the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 into law. The Act included the establishment of a Job Corps for job training for young women and men, a college Work-Study Program, and Head Start, for helping to create a strong educational foundation for young children. Over the next two years, food stamps, Medicare/Medicaid to provide healthcare support, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) were added to the portfolio of programs. In January 1965, New York Times’ writer James Reston acknowledged that Johnson’s War on Poverty was “attacking the indifference of an affluent society, gathering facts about the poor and experimenting with cooperative ways” of assisting.

Poverty wasn’t only on President Johnson’s mind in the mid-1960s. In a sermon delivered at Ebenezer Baptist church on July 4, 1965, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. reflected on his “I Have a Dream” address from the March on Washington, D.C. two years before, acknowledging that his dream had been shattered by seeing the number of Black men and women without jobs, and by seeing how many persons, White and Black, were living in poverty. His attention to poverty among Black and White persons continued: In November 1967, Dr. King announced a Poor People’s Campaign to the staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Dr. King recognized that education, jobs and fair wages were essential to creating a just society, and until our country could create economic stability for more of our people, poverty would continue to be debilitating. Although Dr. King was assassinated in April 1968, SCLC moved forward with the Poor People’s Campaign in May 1968.

President Johnson had claimed 1976 as a date on which poverty would end.

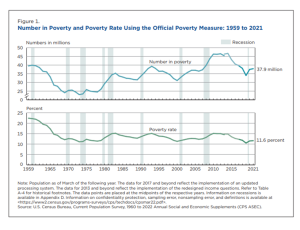

Of course, poverty did not end in 1976, but the intentional focus from the Economic Opportunity Act seemingly had brought about a substantial decrease: The Census Bureau reported that approximately 12% of the U.S. population lived below the poverty level in 1976, down from the 20% level reported before the Economic Opportunity Act.

But even by 2021 – and in spite of the measures that have been employed over the past ninety years – the national poverty rate was still estimated to be 12.8% of the population; and, 16.9% of children under 18 were then estimated to be living below the poverty level.

How is it that the poverty rate has not markedly decreased from 1976 to 2021 – despite efforts to subdue it, and reported historically low unemployment?

Putting Matthew Desmond into conversation with the New Deal, the War on Poverty: Poverty Abolition?

In Poverty, by America, Matthew Desmond posits that Americans can be poverty abolitionists, and that the choices we make individually can collectively affect outcomes and eradicate poverty. Desmond points to seemingly reasonable ways to address poverty – by demanding fair wages for workers (and rejecting “[p]overty wages [that] allow rock-bottom prices”), investing in affordable housing for working families, and, to the extent possible, making anti-poverty choices among the places where we shop and do business. Desmond argues that we can change the nation’s conversation around poverty, and that committed effort could end poverty: Predatory lenders who take advantage of workers needing short-term funds, landlords who rent uninhabitable dwellings to economically-challenged tenants at exorbitant costs, enterprises that exploit laborers through unsustainable schedules and poor conditions, and businesses illegally hiring minor children might need to reconsider their business practices to remain competitive players.

But then what?

Desmond’s use of the term, abolitionist, calls to mind the persons in the United States, the U.K., and Europe who stood firmly against the continued slave trade with which many countries had engaged from the Sixteenth through the Nineteenth centuries. By 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had abolished the slave trade in this country. Part of the goal of Reconstruction was help formerly enslaved persons secure paying jobs and income that would allow them to transition into productive and independent lives. The role of the Freedmen’s Bureau, accordingly, was to provide federal assistance to aid in the transition from slavery to freedom. In his book, And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, Jon Meacham observed, the [Freedmen’s] Bureau was “brought into being with Lincoln’s signature…to feed the hungry, clothe the impoverished, provide health care, establish schools, negotiate fair wages, and offer rudimentary judicial protections…it was…the beginning of a kind of reparation for the system of slavery that Lincoln had decided could not stand.” (Meacham, 362)

We might consider the Freedmen’s Bureau to be the first New Deal.

But Reconstruction did not proceed as Lincoln and other advocates intended. A brief window during which formerly enslaved persons found jobs, were elected to public office and worked to form communities ended abruptly, and measures believed to be guaranteed by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution (the Reconstruction Amendments, respectively granting freedom to enslaved persons, extending to them equal protection and due process under the law, and granting the right to vote) – were not effectuated. Instead, segregation, Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, meant to continue to separate and suppress black persons, raged on.

The voices that had been so ardently calling for abolition did not seem to rise above the voices calling for segregation and separation. Perhaps it was possible to think of enslaving others as a moral wrong without thinking of a formerly enslaved person as a next-door neighbor, one who sat in the same pew at worship, one whose children sat in the same classroom with one’s own, or one who worked side-by-side on a job.

Perhaps, in the same way, it is possible to think that there is a moral wrong for so many persons and institutions to benefit from poverty without wanting to make any personal sacrifices to help the impoverished.

Desmond is correct that Americans becoming poverty abolitionists would change the conversation: The world’s wealthiest nation can markedly decrease poverty. But true poverty abolition calls not only for a willingness to make personal concessions and set aside self-interest, but it calls for long-term, sustainable initiatives of which the public won’t grow tired or disinterested. From the Freedmen’s Bureau, to the New Deal, to the War on Poverty, we’ve seen many initiatives (employment, wages, education, food and housing support) that could advance the anti-poverty cause. Now we have to stick to those objectives – and not allow anti-poverty voices to be drowned out yet again.

And this may well be the point at which the faith community necessarily enters the conversation. How else do we hope for transformed hearts to allow us to see neighbors as having been made in the image and likeness of the Creator – and worthy of all of our support to rise above poverty?